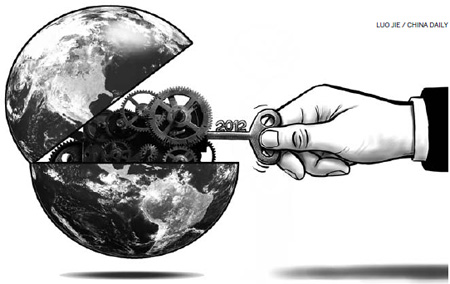

Debate: 2012

(China Daily) Updated: 2011-12-26 08:04Justin Yifu Lin

Industrialization's second golden age

"The golden age of finance," economist Barry Eichengreen has said, "has now ended." If that is true - and let us hope that it is - what follows will most likely be a new golden age of industrialization.

Historically, except for a few oil-exporting economies, no country has ever become rich without industrializing. Thus, all eyes nowadays should be on our economies' real sectors. Confronted by the global financial crisis that looms over Europe, political leaders around the world are waking up to a stark new reality: unless the developed countries stop relying excessively on financial deal-making and start to rebuild from the ground up, they will lose their current standard of living.

The global community must look beyond the eurozone and sovereign-debt crises and pay attention to the opportunity of structural transformation in the developing world's real sectors. By structural transformation, I mean the process by which countries climb the industrial ladder - their workforces move into higher value-added manufacturing sectors as their sources of production advance.

Throughout 2011, I was struck by the potential for less-developed countries - including in Sub-Saharan Africa - to emulate successful industrializing East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, China and Vietnam. Indeed, by focusing development efforts on the comparative advantages of poorer countries, we can rebuild confidence in the business sector and reinvigorate investment in job creation - not only in developing countries, but also in advanced economies.

The current global financial crisis, which is rooted in the advanced countries' structural problems, requires investment and innovation policies, in addition to monetary or fiscal measures.

In advanced countries, research and development costs are quite high, because their technologies and industries are already in the vanguard. By contrast, developing countries, including those in Sub-Saharan Africa, have the potential to expand their industrial sectors rapidly, because they can borrow technology from the advanced countries with little risk and at low cost. So developing countries' backwardness in terms of technology and industry means that they can grow for decades at an annual rate several times that of high-income countries before they close the income gap.

This May, in Maputo, Mozambique, I delivered the United Nations University's annual World Institute for Development Economics Research(WIDER) lecture on development. I explained how the winning formula for developing countries is to build up the same tradable industries that have been growing for decades in wealthier countries that have endowment structures similar to their own.

The pattern of flying geese is a useful metaphor to explain this idea. Beginning in the 18th century, the less-developed West European and East Asian countries followed their more successful neighbors: emulating a flying-geese pattern, they benefited from the leaders' tailwind as they first industrialized and then became advanced countries themselves.

Large, dynamic emerging-market economies (particularly Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) that have industrialized quickly offer unprecedented opportunities for other developing economies to emulate their success - and thus to jumpstart their own industrialization processes. China - once a "follower goose" - is on the verge of becoming a leader, with the potential to relocate 85 million low-skilled manufacturing jobs in the coming decade.

The scale of this shift is huge when compared with the 9.7 million jobs that Japan created in the modern sector in the 1960s, or South Korea's 2.3 million modern jobs in the 1980s. And a similar trend will arise in other emerging-market economies. In fact, it is already happening: China's outward foreign direct investment reached $68 billion in 2010, exceeding that of Japan and the United Kingdom. India, Brazil, Russia and South Korea are not far behind. Moreover, India's outward FDI is heavily concentrated in the manufacturing sector, accounting for 42.7 percent of the total in 1999-2008.

For developing countries to benefit fully from industrial upgrading in China and other large emerging-market economies, their governments must identify tradable industries that are consistent with their latent comparative advantage. They also must help private firms resolve information, coordination and externality issues in the process of industrial upgrading.

Rapid industrialization in developing countries will require large imports of capital equipment from advanced countries. Given that developing countries have accounted for as much as two-thirds of global growth in GDP and imports over the past 5 years, focusing on how to foster development in their industrial sectors could benefit advanced countries by helping boost demand, thereby pulling the world out of its economic malaise.

In short, the imminent golden age of industrialization in developing countries will help create jobs and spur recovery in advanced countries. The benefits of this new era will be two-pronged: it will contribute to the achievement of the UN Millennium Development Goals - the plan to cut world poverty in half by 2015 - and also will help drive a global recovery. Then, we may see a golden age for all.

The author is chief economist and senior vice-president for development economics at the World Bank, and the author of Demystifying the Chinese Economy.

Project Syndicate

(China Daily 12/26/2011 page9)