A step in the right direction

By Qinwei Wang (China Daily) Updated: 2012-04-13 08:07

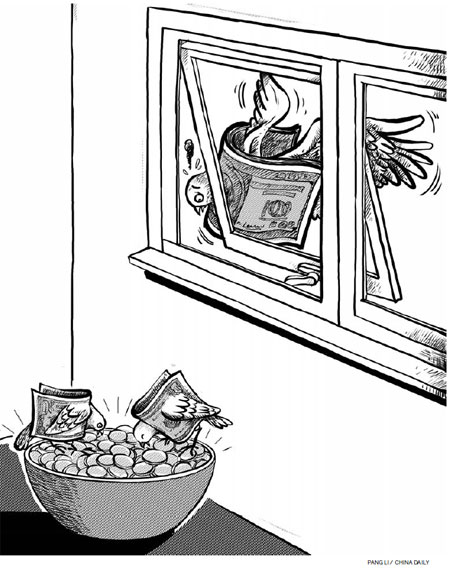

China's securities regulator recently announced that it will raise the total amount that foreigners are allowed to invest in the country's stock and bond markets. This is the latest in a series of moves to relax the controls on cross-border capital flows. But while this has helped to lift equity prices, the wider impact will be limited unless there is faster progress on reforming the currency regime and State-regulated banking system.

Under the new initiative the amount that can be brought into the country under the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) scheme, which is the only way overseas investors can invest in China's domestic securities markets with foreign currencies, has been increased from $30 billion to $80 billion.

Meanwhile, foreigners will also be allowed to bring 70 billion of offshore renminbi funds ($11.1billion) to the mainland through the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor scheme (RQFII), up from 20 billion renminbi when this programme was launched a few months ago.

The news seems to have immediately boosted market sentiment. China's equity prices outperformed in the region when its stock markets re-opened last Thursday after the three-day Qingming Festival holiday: the Shanghai Composite Index rising almost 2 percent, following a fall of nearly 7 percent over the previous month.

That said, the support to stock prices is likely to be short-lived and the overall impact limited. After all, the amount of approved QFII and RQFII funds is currently only around 1 percent of the total market value of stocks traded on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, although if the quotas were fully used, the ratio would be more than triple, much higher than any previously. However, the fact is, even the existing quota has not been fully used, only $25 billion of the QFII quota has currently been taken up.

The quotas are not the only constraints, after the previous cap lift in 2007, no more than one fifth of the new quotas were approved for individual investors each year. Meanwhile, foreign investors themselves may be cautious, because China's financial markets are immature and equities have performed poorly over the last few years. What's more, since both policymakers and the market appear less convinced now than in the last few years that the renminbi is significantly undervalued, the pace of renminbi appreciation will probably slow significantly this year compared with the 5 percent gain in 2011. In fact, the renminbi's value against the dollar has changed little since the beginning of the year, also reducing the appetite of foreign investors.

But the bigger picture is that this is China's latest step towards opening its capital account and further facilitating the internationalisation of its currency. The government may have realized that sooner or later the renminbi would lose its attraction for foreigners if there were no further easing of controls on capital account convertibility. Nonetheless, hopes of unfettered cross-border flows any time soon will probably be disappointed, as there are two preconditions for the opening of the capital account: the currency will need to freely float, acting as a means to release any transient pressure affecting the economy, while the financial system will need to become sufficiently developed, so that it can cope with rapid inflows or outflows of money. Both of these seem a long way away.

Admittedly, the government has signalled that the renminbi's daily trading band might be widened soon. This would be symbolically important, but in practice it doesn't necessarily mean that the government will allow the market freer rein to determine the renminbi's level. It will be more important to watch how the renminbi actually performs.

Policymakers seem to have also realized that one of the priorities should be speeding up reform in financial markets, with Premier Wen Jiabao recently commenting that China's State-owned banks are a "monopoly" that must be broken. A few days before his comments, the State Council approved a pilot financing scheme in the wealthy city of Wenzhou to improve the role of private funds in financing, which may help to find the answer.

However, there are all kinds of difficulties and obstacles facing banking reform. Recent developments such as the use of banks to finance China's stimulus packages also make the task harder than a few years ago. Banks would struggle to roll over existing loans profitably if they had to compete freely for deposits.

The author is China economist at Capital Economics, a London-based independent macroeconomic research consultancy.

(China Daily 04/13/2012 page9)