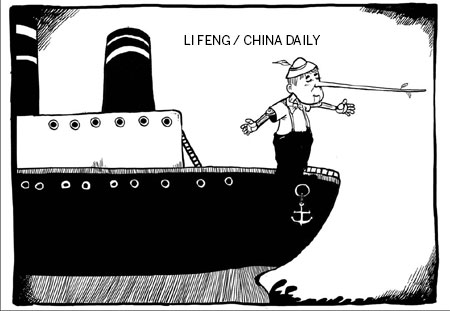

Hoax just the tip of the iceberg

By Gao Zhuyuan (China Daily) Updated: 2012-04-26 08:12

Not all of the Titanic 3D made it to Chinese screens, as the scene where Jack draws a picture of the naked Rose, was cut by China's State Administration of Radio, Film and Television.

An online message purporting to be from the SARFT said the scene was cut for fears that viewers may reach out towards Rose due to the vivid 3D effects, and thus interrupt others and cause potential conflicts.

The "statement" soon spread like wildfire through China's social networks and media at home and abroad picked up on it, even Titanic director James Cameron mentioned it when he appeared on the US talk show The Colbert Report.

Unfortunately, no one seems to have taken the time to read the original post carefully as it carried a "fake news" disclaimer at the bottom.

The fake statement, although it caused no serious harm, has highlighted how online rumors can quickly snowball out of control.

The student who wrote the post claimed he stood "in the shoes of SARFT" because he was confused by the administration's criteria for cutting scenes and he intended it as a joke. But it is a good example of how rumors and hoaxes gain legs on the Internet and eventually influence real life.

The rumormongers that forwarded the statement without the fake news warning, the domestic and overseas news media that failed to verify the statement, and the authority itself, which, as it has in the past, failed to respond to the fake statement all gave life to the hoax.

Many experts believe that the Internet is self-correcting arguing the truth spreads as quickly as rumors, which may well be true in some cases, but it is not always the case.

It was the original writer that finally crushed the fake SARFT statement almost one week after the release of his original post.

In fact, rumors are rife in cyberspace, especially social networks, and in the past few years there have been many rumors on the Internet that have disrupted social order.

One example is the panic buying of salt in some parts of China, which was triggered by the rumor that iodized salt could help prevent the harmful effects of radiation exposure. The rumor played on people's fears about the seriousness of Japan's nuclear emergency as a result of the tsunami in March last year.

Many critics are quick to blame Chinese netizens for irresponsibly forwarding unauthenticated information and thus fueling the spread of rumors. But while Chinese netizens play their part, such accusations fail to take into account the gullibility potential of China's online population. The latest data from the China Internet Network Information Center shows that China's Internet population hit 513 million by the end of 2011, of which some 44 percent have only a junior middle school education or less.

Many Internet users simply do not have the knowledge or ability to identify fact from fiction. Neither do they have access to media literacy education either inside or outside the school system that their counterparts in the United States and other European countries do. They do not have the opportunities to acquire the skills necessary to question and analyze what they watch, hear and read on the Net.

But just because they are not capable of analyzing messages does not mean they should spread rumors.

The Internet has accelerated the flow of information but it does not discriminate between true and false.

Netizens need to resist the urge to cyber-gossip and develop online ethics so they do not spread information unless they know it to be true.

By doing so, Internet users can be a rumor-crushing force.

After all, being qualified with professional training did not prevent the media from disseminating the Titanic rumor. The media should remember the ethics of journalism. That so many rumors are deemed credible is because journalists fail to verify stories.

The author is a writer with China Daily

gaozhuyuan@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 04/26/2012 page9)