Living with the Internet rumor mill

'Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it," said the great 18th century writer Jonathan Swift in his essay, The Art of Political Lying. When Swift made his sage observation, the mass circulation press (and its readership) was in its infancy.

More than a century later, a mature print media - the so-called yellow press - sparked the 1898 Spanish-American War by claiming that the USS Maine had been destroyed by a Spanish mine. Modern investigations suggest that the spontaneous combustion of volatile bituminous coal was a more likely cause of the explosion on and sinking of the battleship.

Four decades later, using the then new media of radio, Orson Welles created a mass panic with his "War of the Worlds" broadcast, saying Martians had invaded Earth. After the Lushan earthquake in Sichuan province on April 20, a similar apocalyptic rumor, this one warning that a big quake would destroy the provincial capital Chengdu, needlessly sent many people in Sichuan into a tizzy.

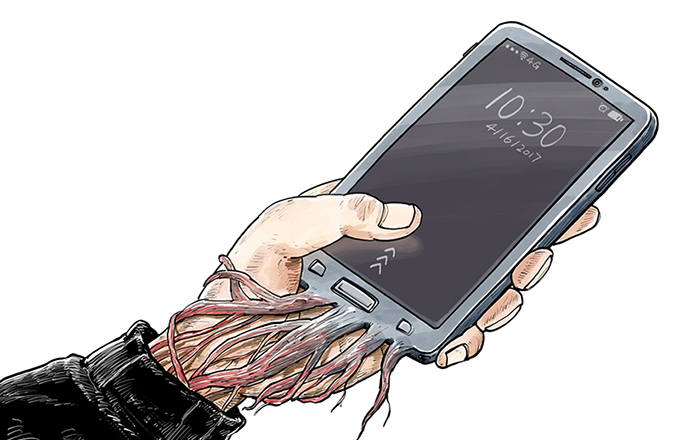

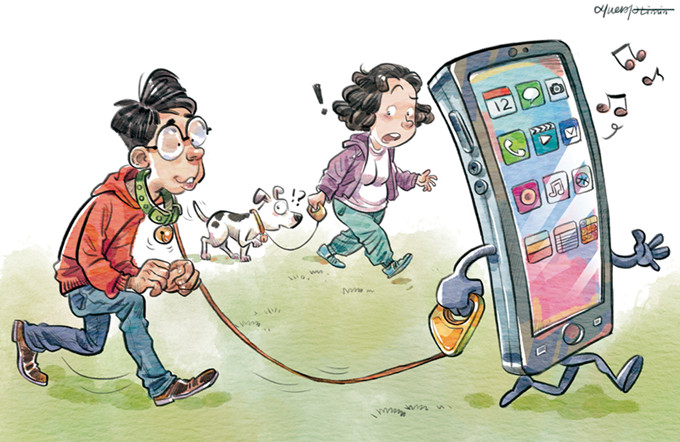

The earthquake rumor, of course, was spread through the Internet. Thanks to the speed at which word travels through the Web and the number of people who surf it today, falsehood really does fly in cyberspace, while truth all too often comes limping after it.

This situation is more or less tolerated in the United States as part of the tradeoff for free expression. Indeed, to successfully prosecute or sue someone for libel, a person has to not only show that the statement made was false, but also prove that it was made with malicious intent. The second criterion is difficult to meet, and anyone who is a "public figure" is fair game for ridicule.