Peddling new solution to old problem

By Zhang Zhouxiang (China Daily) Updated: 2013-09-27 07:01

Xia Junfeng, a street vendor, was executed on Wednesday for killing two chengguan (or city management officers) in 2009. Xia, an unlicensed kebab seller in Shenyang, Liaoning province, was detained after being allegedly roughed up by chengguan in May 2009. In the chengguan office, he stabbed the two officers before fleeing the scene.

Many netizens have paid condolences to Xia's family, including his wife and 11-year-old son (which now survives on the meager earnings of Xia's parents), and criticized chengguan for their high-handed and violent behavior with vendors.

But we should understand that the two city management officers were also breadwinners of their families and victims of the tragedy. So instead of despising city management officers, we should reflect on the city management system itself.

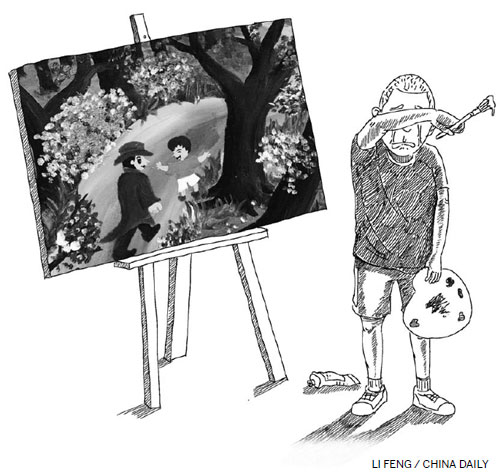

Chengguan has been hitting the headlines with increasing frequency because of their conflicts (many of them violent) with unlicensed street vendors. So what is wrong with the chengguan system and how can it be rectified?

According to the latest urban management regulation of Beijing - published in February this year -the duties of chengguan include "maintaining order in the city" and "penalizing unlicensed business". Chengguan is just a part of the bigger mechanism to "manage a city's image".

Street vendors and peddlers are among the most unwelcome elements for chengguan. In fact, many cities have banned peddlers and vendors because "they damage the city's image".

Most of the peddlers are farmers or laid-off workers trying to earn a living. And since a majority of them lack the skills to compete in the job market, they have no option but to rely on peddling and - if they are lucky - manage enough money to start a micro business to keep the home fire burning.

Most peddlers in China cannot afford to rent a stall in a market. A recent Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce survey shows that the rent of a stall in a vegetable market accounts for 62-79 percent of the total cost of vegetables. Even in small cities like Yantai, Shandong province, a stall could cost as much as 1,500 yuan a month in 2011, forcing many self-employed people out of markets and into the streets. Ironically, a considerable part of the high cost of stalls is spent on the upkeep of the government's market regulating agencies such as chengguan. And with so many people forced to sell goods on streets, conflicts between vendors and chengguan are bound to happen.