World Bank: China could achieve both high growth and deleveraging

|

|

John Litwack, the World Bank’s lead economist for China, is interviewed by the China Daily website. [Photo by Cong Ruiting/chinadaily.com.cn] |

Editor’s Note: In a wide-ranging interview with the China Daily website, John Litwack, the World Bank’s lead economist for China, commented on China's Q3 data and discussed the opportunities and challenges both China and the world face in 2017. He emphasized that as China can still achieve high growth and deleveraging, the welfare of the Chinese people could continue to grow very quickly.

1. What’s your evaluation of the Q3 data? Many analysts note that the PPI, the producer price index, which gauges factory-gate prices, rose by 0.1 percent year-on-year in September after falling in China since March 2012. Does the PPI growth hint reform measures are taking effect?

The 2016 Q3 numbers look good generally. China has maintained 6.7% growth. Despite having some slowdown in July, growth picked up in August and September. One thing we look at when you see China’s growth is that output growth seems to follow credit growth so closely, so we also have seen a sign of acceleration in the growth of credit in August and September. The fact that the pace of growth in credit more than twice that of GDP raises questions of sustainability. But when we look at the indicators like PMI, the Chinese economy is doing pretty well in terms of growth and in terms of outlook for business.

When you look at the PPI, it is common to cite the year on year number, and it’s true that that number had been negative until very recently. But if you look at the monthly numbers, the PPI has actually been positive for all of this year, We think that is a good sign, a negative PPI would be a negative sign for the economy that problems like over-capacity. There are two primary factors that can explain the recent changes in the PPI: one is commodity prices. One reason why the PPI has been very low and negative in recent years is that commodity prices have been falling. Alternately, one reason why the PPI turned positive this year is because of a recovery in the prices of commodities like oil, steel and coal in of world markets.

The second factor is progress in China’s reforms, in particular addressing excess capacity issues. That’s very important.

There’s still a future for the coal and steel industries, but perhaps a smaller role. So in part the reform is about downsizing the most inefficient parts of these industries, and rebalancing the economy to other sectors, which is obviously a difficult process because it involves a lot of workers and some areas of China very much depend on these sectors. It’s a difficult process for any country to move concentration from one sector to another. But we hope that China will continue to progress in this area. We’re working with the Chinese government to develop instruments to help support and re-train workers from these over-capacity industries so they can work productively elsewhere.

2. Could you give some predictions around the growth rate of China’s GDP for all of 2016, and your outlook for 2017? Is it possible that China’s economy could bottom-out at the end of 2016 and then experience a rebound in 2017?

I think an economic growth rate in China of somewhere around 6.7 percent is very possible in 2016. The last three quarters’ data indicate stable growth, it looks like this growth is continuing. So we think 6.7 percent is quite probable. In 2017 we expect a bit lower growth, maybe close to 6.5 percent, although this is very uncertain. One big factor of uncertainty is the world economy, which has been much weaker than we expected this year, particularly in international trade. In fact Chinese exports have been a negative component for growth in 2016. So domestic demand has compensated for the decline of net exports.

Next year it is possible that China could achieve a boost from higher exports, as there’s some expectation that the world economy will pick-up. But this is very uncertain. We have also seen a rise of protectionism in many countries that could also impact China’s exports. It could be that China will achieve more growth in exports next year, but it is also possible that it won’t. Another important component of growth in 2016 is real estate, which grew at 8.9 percent over first three quarters of the year. We know from international experience that a very rapid growth in real estate like this combined with very rapid price increases is usually unsustainable and volatile. The government is aware of that, which is why measures have been taken to cool down the housing market. We agree with those measures and think they are appropriate. For this reason, however, growth in real estate in 2017 will likely be slower.

Another question relates to infrastructure and public investment, which was an important component of growth in 2016. I’m sure that it will also be important in 2017, but there is also the question of credit growth. Rapid credit growth is increasing macro-economic risks that need to be addressed. So it would be a positive step to prioritize a slowdown of credit growth, even though it may mean a bit less growth in investment and the economy in the short run.

So those are the reasons why we think GDP growth might be a bit lower in 2017, but 6.7 percent is still very high given what the world economy is going through now. So we believe China could continue to achieve strong growth next year, even if a little slower than in 2016, while making progress in reform and bringing credit growth under control. In our view, this would make 2017 a very successful year for China.

3. The World Economic Outlook 2016 issued by the IMF calls for countries all over the world to use coordinated cooperation and effective policy levers to boost growth prospects; what are your views on using these two tools properly?

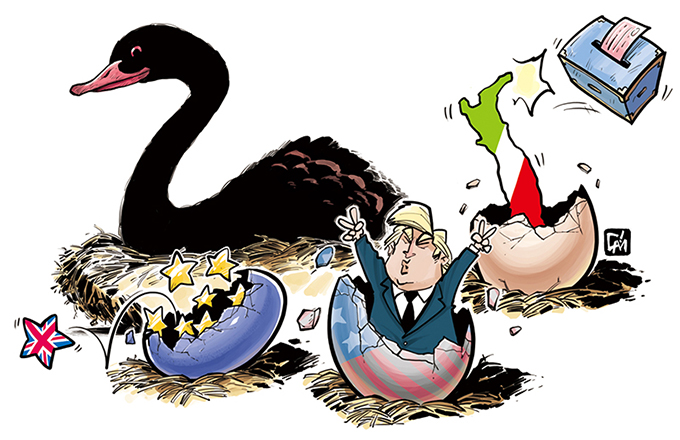

The world economy’s growth has become very slow, much slower than expected, and faces a dilemma. The world economy has been stimulating growth primarily through monetary policy and lower interest rates. Now we’re reaching a point where interest rates are approaching zero, there is increasingly little room left to use that kind of instrument to boost growth. Therefore, for governments to be effective in stimulating growth, they need to rely more on fiscal policy, like tax reductions or increases in public spending. Many people now believe that a major infrastructure program in the post-election United States could feed this growth. But we also know from world experience, including that of the EU, that fiscal policies should be coordinated for the world economy to move together in a harmonized manner.

International trade and investment are other questions. More cooperation in these areas could also have a strong positive impact on growth.

4. People are paying close attention to whether the property market can sustain stable development and help investment and resources to flow into areas where they are truly needed. How would you see these two areas in 2017?

Certainly it’s a good thing that the real estate market is growing quickly in China. However, we know from international experience that too fast a pace of growth in real estate can end in instability; it’s not sustainable. So we think that the measures being taken by the government are appropriate and could facilitate the property market to grow in a more stable manner and a bit slower. It would actually be healthier if China’s property market could grow a bit slower in 2017.

There’re many factors in China affecting the relocation of resources to productive areas which would have higher impact on growth. One priority is moving resources for production from over-capacity industries and less productive firms to more productive ones. There is also a question about spending on infrastructure projects. Generally, we see the returns on such projects declining in many areas because Chinese cities already have pretty good infrastructure. Now, some infrastructure investments may be having a much lower impact on longer term growth and development. Many innovative and productive firms in China compete very well in world markets. If they can get more resources in the future, China will probably be better off.

5. What are your thoughts on Public-private Partnerships (PPPs) in China?

We think that PPPs have a lot of promise in China. There can be a good rationale for co-investment between the private and public sectors in many areas. China should note, however, that the world experience in PPPs is quite mixed. The experience in most countries has been a bit complicated, but there are success stories. China has increased the number of PPP projects very quickly, and is encouraging them as a way of rapidly increasing the volume of public financing. In this light, we think that China might benefit from being a bit cautious. Given the limited experience in China with PPPs in the past, and the encouragement that local governments have been given to expand their use, it is natural that the instrument might be used in appropriately in some cases. PPPs create contingent liabilities for government that can end up being a problem at a later date..

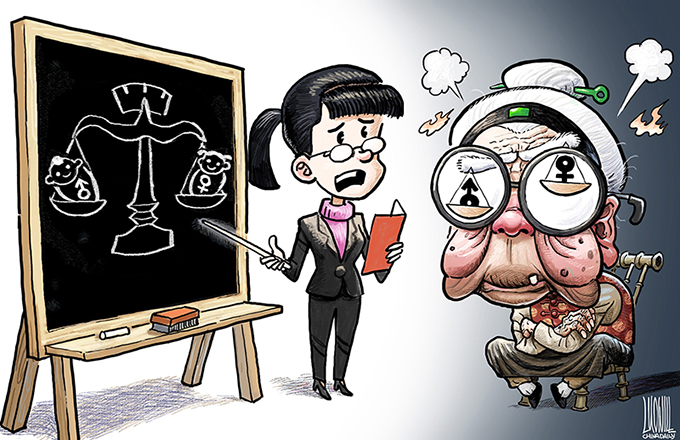

6. The research department of PBOC pointed out that compared to other economies, the ratio of debt and GDP in China’s non-financial sector is still reasonable, while the leverage ratio of the corporate sector continues at a high level which keeps increasing. Would you give some suggestions for de-leveraging? Other countries’ experience seem to show that for the first two years of de-leveraging there may be a negative influence on economic development, but after this period a rebound may be achieved. How can we control the short-term negative influence brought by deleveraging?

This is a very important question for China, because credit growth is still twice the GDP growth and the economy is becoming quite leveraged. For an emerging market like China, the level of credit debt is already becoming high, and may continue to increase unless measures are taken to bring it under control. We think that China will need to address this issue sooner or later. The longer that China waits, relying on its fiscal room and reserves, the most costly it could end up becoming. Even if accelerating the pace of credit growth can generate a bit more short term GDP growth, this could a growth disruption or slowdown in the medium term. We therefore think that it would be wise for China to continue strong efforts to bring credit growth under control.

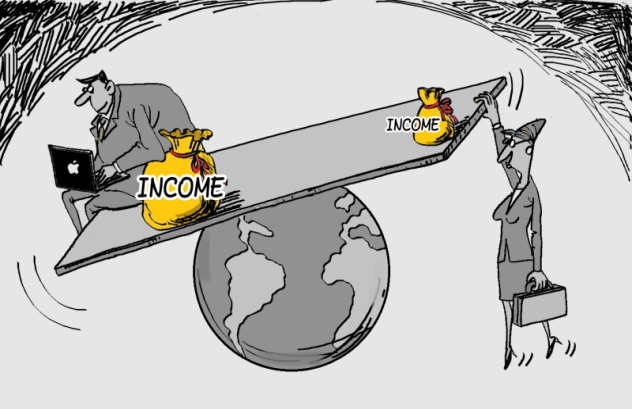

While the impact on short term growth may be negative, we should keep in mind that short-term GDP growth is not the only important economic indicator. What we care about most is the welfare of the Chinese people, and the income of the Chinese people has been growing faster than GDP. If money would be spent, for example, building roads or buildings that nobody is using, that would add to short-term GDP growth but bring no benefit to the people. So we think the government should continue to support policies to ensure that the income of the population grows faster than GDP. Fortunately, this is a natural trend for a country that is rebalancing away from exports and toward domestic demand. Even GDP growth slows down a bit more, it will still be very high by international standards. Thus, China can achieve simultaneously strong growth, rapid welfare improvements, and deleveraging. Increasing incomes of population also directly feed domestic demand, which is driving growth. China cannot rely on exports any more to drive growth, given the world economic situation. So it’s domestic demand that drives growth.

So the rebalancing process is not necessarily a painful thing for the general population, although social support for workers directly affected in poorly performing industries is extremely important. The welfare of the Chinese people can continue to grow very quickly even if the GDP growth rate becomes somewhat lower.