Time to adapt to an automated future

|

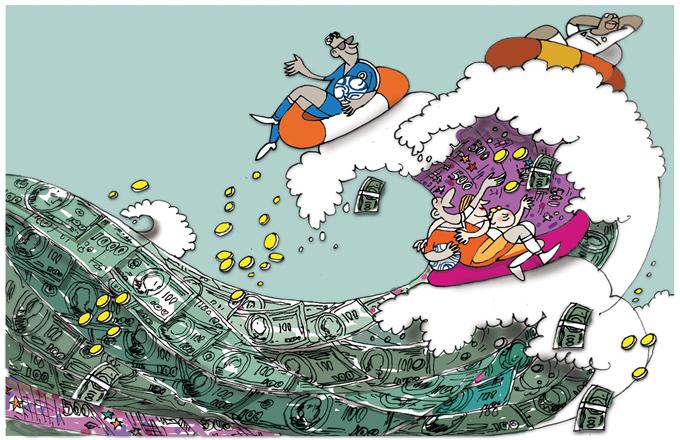

| CAI MENG/CHINA DAILY |

The tsunami of technological innovation will continue to change profoundly how we live and work, and how our societies operate. In what is now called the Fourth Industrial Revolution, technologies that are coming of age-such as robotics, nanotechnology, virtual reality, 3D printing, the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence and advanced biology-will converge. And as these technologies continue to be developed and widely adopted, they will bring about radical shifts in all disciplines, industries and economies-in the way that individuals, companies and societies produce, distribute, consume and dispose of goods and services.

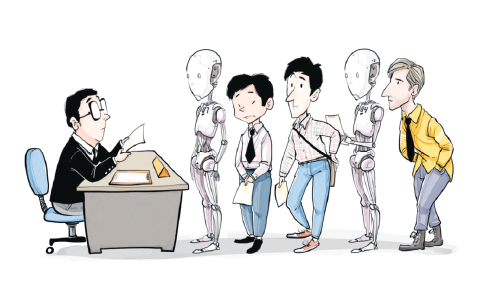

These developments have given rise to questions about what role humans will play in a technology-driven world. A 2013 University of Oxford study estimates that close to half of all jobs in the United States could be lost to automation over the next two decades. On the other hand, economists such as Boston University's James Bessen argue that automation often goes hand in hand with the creation of new jobs. So which is it-new jobs or massive structural unemployment?

At this point, we can be certain that the Fourth Industrial Revolution will have a disruptive impact on employment, but no one can yet predict the scale of change. History tells us that technological change more often affects the nature of work, rather than the opportunity to participate in work itself.

The First Industrial Revolution moved British manufacturing from people's homes into factories, and marked the beginning of hierarchical organization. This change was often violent, as the famous early 19th century Luddite riots in England demonstrated. To find work, people were forced to move from rural areas to industrial centers, and it was during this period that the first labor movements emerged.

The Second Industrial Revolution ushered in electrification, large-scale production, and new transportation and communication networks, and created new professions such as engineering, banking and teaching. This is when middle classes emerged and began to demand new social policies and an increased role for government.

During the Third Industrial Revolution, modes of production were further automated by electronics and by information and communication technology, with many human jobs moving from manufacturing to services. When automated teller machines were introduced in the 1970s, it was initially assumed they would be a disaster for workers in retail banking. Yet the number of bank branch jobs actually increased over time as costs fell, only that the nature of the job changed-it became less transactional and more focused on customer service.

All the industrial revolutions were disruptive by nature, and the fourth will be no different. But if we keep in mind the lessons of history, we can manage the change. First, we need to focus on skills, and not just on the specific jobs that will appear or disappear. If we determine which sets of skills we will need, we can educate and train the human workforce to leverage all of the new opportunities that technology creates.

Second, experience shows us that disadvantaged classes must be protected; workers who are vulnerable to being displaced by technology must have the time and means to adjust. And to ensure the Fourth Industrial Revolution translates into economic growth and bears fruit for all, we must work together to create new regulatory ecosystems. Governments will have a crucial role to play, but businesses and civil society leaders will also need to collaborate with governments to determine the appropriate regulations and standards for new technologies and industries.

I don't assume this will be easy. Politics, not technology, will determine the pace of change, and implementing the necessary reforms will be hard, slow work. It will require a mix of forward-looking policymaking, agile regulatory frameworks and, above all, effective partnerships across organizational and national boundaries. A good model to keep in mind is Denmark's "flexicurity" system, in which a flexible labor market is paired with a strong social safety net that includes training and re-skilling services for all citizens.

Technology may be advancing rapidly, but it will not cause time itself to collapse. The momentous-indeed, revolutionary-changes ahead will take place over many decades, not as a big bang. Individuals, companies and societies do have time to adjust; but they cannot afford to delay. Creating a future in which all can benefit must start now.

The author is managing partner and chairman, Global, at A.T. Kearney.

Project Syndicate