How the Belt and Road could change the 21st century

Until recently, globalization was led by the west and benefited only a few advanced economies. After China's three decades of rapid growth, the Belt and Road Initiative hold potential for more inclusive globalization.

On the weekend, Beijing was flooded with almost 30 heads of state and government leaders, 1,500 delegates from over 130 nations, and over 70 international organizations for the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation.

As the forces of globalization are lingering in the advanced world, the Forum reflected new commitment to more inclusive globalization, particularly by emerging and developing economies. By 2050, their contribution to global GDP growth is expected to climb from 68 percent to 80 percent.

The Forum precipitates huge investments in new roads, railways and ports while facilitating access to vital capital, goods and services, especially to those economies that benefited so little from the post-war globalization. The investment in infrastructure is likely to accelerate industrialization and growth opportunities in nations where living standards remain low, but growth potential is high.

Focus on economic development

In the west, the Belt and Road (B&R) is still portrayed as a new plan. Yet, President Xi Jinping raised the initiative of jointly building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road in the autumn of 2013.

If the original belt reflected the ancient world economy until the Italian Renaissance, the B&R includes countries on the original Silk Road through Central Asia, West Asia, the Middle East and Europe. It also features a maritime road that links China's port facilities with the African coast, through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean.

The B&R has potential to redirect domestic overcapacity and capital for regional infrastructure development to improve trade and relations with Southeast Asia, Central Asia and Europe – and, over time, across the Americas and Sub-Saharan Africa.

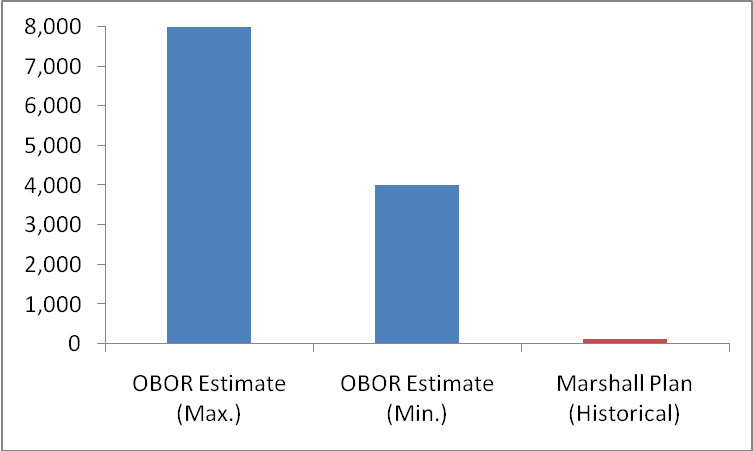

The B&R has been compared with the post-war Marshall Plan, which was designed to support the European recovery and to insulate the Soviet Union. There are parallels, but also major differences.

Presumably, the Marshall Plan was created to help rebuild economies in Western Europe for four years beginning in April 1948. While there is no consensus on exact amounts, the cumulative aid may have totaled $13 billion (some $130 billion in 2016 dollar value). These efforts pale in comparison with the B&R, which involves far greater cumulative investments, which are currently anticipated at $4 trillion to $8 trillion, depending on timeline and scenario estimates (Figure 1).

Unlike the Marshall Plan, the B&R does not predicate participation on membership or tacit support of military alliances. It is focused on 21st century economic development – not on 20th century Cold War.

Huge expenses of geopolitics

The Marshall Plan was predicated on participation in the US-led North American Treaty Organization (NATO). Historically, almost 75 percent of the total aid went to just five countries: the United Kingdom, France, West Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, which became NATO's core members.

Today, NATO still accounts for over 70 percent of all military spending in the world (United States 38 percent, non-US NATO: 32 percent), although friction about NATO financing by members reflects underlying pressures among the founding members.

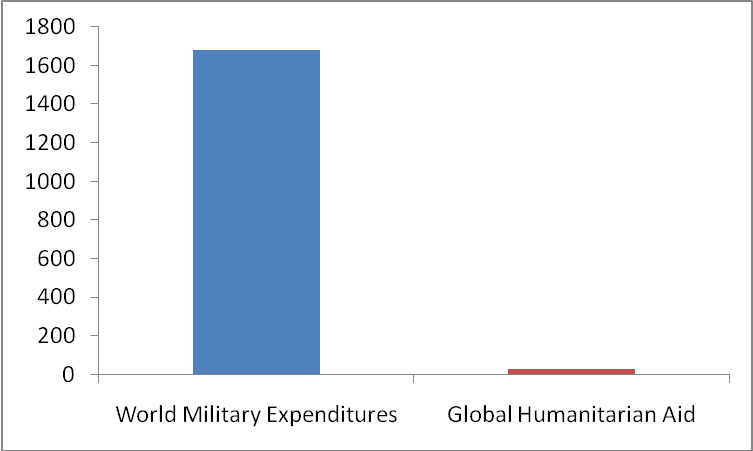

While much is made about spending on humanitarian aid by the west, particularly the US and Europe, it should be seen in context. In 2016, world military expenditure is estimated to have been $1.68 trillion, according to SIPRI research. In turn, international humanitarian assistance reached a record high of $28 billion in 2015, according to the most recent Global Humanitarian Assistance Report (Figure 2).

In brief, west-led humanitarian assistance is less than 2 percent of world military expenditures, which is led by NATO. That's untenable over time, especially as more than 90 percent of global humanitarian aid goes to long and medium-term recipients.

Need for global cooperation

Unlike advanced economies, emerging and developing nations have neither the ability nor willingness to over-invest in military spending. In per capita terms, China ($156), India ($42), and even Russia ($481) invest a lot less than the US ($1,885), or major European economies ($500-$860) in military spending.

Moreover, China does not predicate entry to the B&R on membership in military alliances, as the US once did. That is vital. When NATO's rearmament replaced economic development as the west's primary goal in the post-war era and when the Cold War divided the world, instability and economic volatility surpassed stability and economic growth in the global agenda. That benefited mainly a few advanced economies but not the decolonizing nations, which were penalized by costly conflicts that were exported to the Third World as the direct result of the Cold War.

It is these historical failures in economic development that the B&R has potential to alleviate over time. Through renewed global cooperation, the rise of more inclusive multilateral inter-governmental development banks. and massive new infrastructure initiatives in pivotal emerging economies, the Belt and Road has the potential to change the 21st century – for the better.

The author is the founder of Difference Group and has served as research director at the India, China and America Institute (USA) and visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore).

|

|

Figure 1 OBOR and Marshall Plan Expenditures ($ billions) |

|

|

Figure 2 World Military and Humanitarian Expenditures, 2015 ($ billions) |