Borrowers face costly payback

Updated: 2012-02-14 07:56

By Li Jing and He Na, and Xu Junqian (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Chinese businesswoman Wu Ying was convicted of illegal fundraising and defrauding investors on April 16, 2009, after a trial at Jinhua Intermediate People's Court in Zhejiang province. She was later sentenced to death, a punishment that has raised questions among many experts. [Hong Bing / for China Daily] |

Open to abuse

Without a proper monitoring system, however, experts warn that private lending poses a threat to the health of China's economy.

Private lenders enjoy no legal protection, meaning that unpaid loans often result in disputes and, in extreme cases, violence. Meanwhile, the existing system is also open to money launderers.

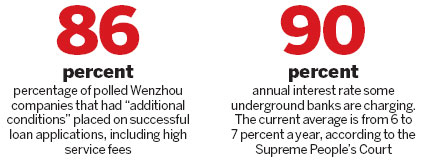

Authorities have been cracking down on the illegal practice since October, when a number of Wenzhou bosses fled or killed themselves to avoid paying back high-interest loans. Now that the tap has been turned off, small business in the city has been hit even harder. The owner of a shoe factory, which has been in operation since 2003, told China Daily that this year is the first time he has been unable to restart the production lines immediately after the Spring Festival holiday.

"We just don't have enough money," he said, on condition of anonymity. "Without cash flow, we cannot and dare not hire people and receive orders."

With the rising costs of labor and materials and the tightened bank policies, he said that the government crackdown on private lending had been the last straw. "We just hope something concrete can be done sooner or later," he added.

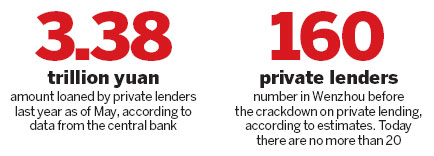

According to Zhou's association, Wenzhou until recently had about 160 private lenders and "guarantee organizations", which are companies or individuals who stand as guarantor on loan applications. Today there are no more than 20.

One lender, who gave his name only as Fu, said he will not even lend money to relatives nowadays, explaining that once the money is "out of my hand, I have little chance of ever seeing it again".

Nine out of ten lenders mostly bankrupt bosses will take the money and flee, he said, adding: "It's a vicious circle."

Legalization of private lending is urgently needed, said Zhou, as well as moves to create more financing options for small and medium-sized enterprises, such as relaxing monetary policies on private banks.

He Tian, a real estate developer based in Zhejiang, agreed. "In some ways, we're luckier than the manufacturing industry, as we barely rely on private lending. Yet, we still need it for emergencies," he said. "The sooner it is regulated, the better and safer it is for both creditors and debtors."

Economists, legal experts and sociologists from across China met to discuss the implications of Wu Ying's case at two seminars in February. Most echoed the call for legalization.

"Private financing has supported the development of China's private sector, so it is worth recognition by the authorities," said Hu at the Beijing Institute of Technology. "That's why Wu's case has attracted so much public attention."

Final decision

The fate of former tycoon Wu now lies with the Supreme People's Court, which is reviewing her case. Hu argues that if her execution is approved, the monopoly by State-owned banks can be further consolidated and would deal a heavy blow to the country's burgeoning private sector.

"Instead, the government should admit the legal status of private lending, support those with good records and establish a set of criteria to bring underground banks to the surface," he said. "This way, it will be easier to monitor and regulate."

There is also no clear legal boundaries between illegal fundraising and reasonable private lending, a fact that has fueled opposition to Wu's death sentence, he said.

Wu grew up in Dongyang, a city in Zhejiang, and started her working life in a relative's a hair salon in 1997.

Within a decade, she was running a conglomerate of hotels, car dealerships and real estate, and was regarded as the country's sixth-richest woman.

At the time, she represented a success story of the robust entrepreneurial spirit that could typically be found in the coastal province in East China.

"Many questions are still left unanswered in Wu's case," Hu said. "For example, she only collected money from 11 lenders, two of whom were her business group's senior executives. They were fully aware of the financial situation.

"How can it be defined as fraud?"

The reporters can be contacted at lij@chinadaily.com.cn, hena@chinadaily.com.cn orxujunqian@chinadaily.com.cn

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|