Doors slam shut on 're-education' system

Updated: 2013-12-11 07:20

By Zhao Xu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Fundamental flaws

Yang first heard about Jiabiangou in the 1960s, but started researching the book in the late 1990s. Stories from Jiabiangou was published in 2002, but banned in 2005, remaining out of circulation until the ban was lifted in 2008.

"The abolition of laojiao is a triumph for society, the intellectuals in particular," said Zhou Yongkun, a law professor at Soochow University in eastern China's Jiangsu province, who is one of the most vociferous critics of the laojiao system. "It's also a triumph for Chinese legal practitioners, and most significantly, the ruling party which has shown genuine interest in acting on people's will, in rectifying social injustice, and improving the rule of law."

Zhou believes the system's fundamental flaw lay in the fact that it effectively allowed people to be deprived of their freedom without even being tried by the courts.

"The 'rightists' hadn't committed any specific crimes, but were thought to be harboring bad feelings against the government as a result of their backgrounds," said Zhou. "Laojiao, which was carried out by an administrative order instead of a court ruling, provided an easy way to store these 'subversive elements' without giving them any due-process rights."

However, despite the faults of the laojiao system, not everyone is willing to denounce it completely. "Any discussion about laojiao has to be put into context to have any real meaning," said Song Lu'an, presiding judge of the administrative division at the High People's Court of Henan province. "In the initial decades after the Communist Party came to power, it needed a mechanism to cement its rule and to push through some of its most important policies, land and economic policy, for example, in the face of strong opposition from certain groups and sectors of society."

"At the time there were no jobs except those provided by the state. And since many 'rightists' had lost their jobs as a direct result of their designation, laojiao farms, which actually paid their inmates a paltry, albeit crucial, wage, could well be those people's last chance to work," he said, pointing to the fact that some "rightists" were ordered to choose between laojiao and unemployment. Fearing the uncertainty of a jobless future, many chose laojiao.

Given his current stance, it's surprising to learn that 17 years ago, when he was a doctoral candidate of law, Song published an article in a Chinese legal magazine, advocating the abolition of laojiao.

"My understanding of the system has deepened and broadened ever since, but I haven't changed my view that China should do away with laojiao, especially now, when the country has adopted a market economy and has built a much sounder and sophisticated legal structure," he said.

But between then and now, there have been many twists and turns, reflected by the evolution of the laojiao system as much as society in general. "From time to time, the voices of the abolitionists were muffled, or even drowned out, by those who attempted to revise and reform the system," said Zhou, the law professor.

Serious questions about laojiao started to be raised when the reform and opening-up policy was implemented in the late 1970s and early 80s. "With fresh air being breathed into Chinese society, people began to openly express their resentment of arbitrary power and their longing for the restoration of law and order," said Zhou.

Uruguay becomes 1st nation to legalize marijuana

Uruguay becomes 1st nation to legalize marijuana

Snowstorm blasts US

Snowstorm blasts US

2013 Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm

2013 Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm

Reuters images of the year - politics

Reuters images of the year - politics

Conjoined babies waiting for surgery

Conjoined babies waiting for surgery

Chinese say their goodbyes

Chinese say their goodbyes

Obama shakes hands with Cuban president Castro

Obama shakes hands with Cuban president Castro

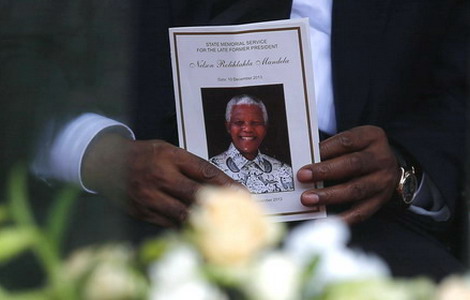

S Africa holds memorial service for Mandela

S Africa holds memorial service for Mandela

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Handshake could signal improving ties

US Congress negotiators reach budget deal

Retirees saddled with kids' costs

Bar lowered for private pilots

Building impact reports will be released

Obama urges Congress to pass budget deal

Beijing announces theme, priorities of APEC

Battle against counterfeit goods enters a new phase

US Weekly

|

|

!['I remember standing at the farm making a tentative inquiry about my husband. A man who was clearly in charge took out a notebook … I thought he was about to tell me where he lived. BUT HE JUST SAID ONE WORD: 'DEAD'.' - HE FENGMING, A RETIRED LANGUAGE PROFESSOR FROM GANSU [Photo provided to China Daily] Doors slam shut on 're-education' system](../../attachement/jpg/site1/20131211/f04da2da78cd1411f43b18.jpg)