Doors slam shut on 're-education' system

Updated: 2013-12-11 07:20

By Zhao Xu (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

![Someone has paid tribute to the deceased with a bottle of liquor. [Photo provided to China Daily] Doors slam shut on 're-education' system](../../attachement/jpg/site1/20131211/f04da2da78cd1411f43b19.jpg) |

|

Someone has paid tribute to the deceased with a bottle of liquor. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

Evolution of laojiao

However, by this time, laojiao was no longer associated with political stance. Instead, it was mainly used to detain people for minor offenses such as petty theft and prostitution. Under Chinese law, these offenses are not serious enough for those who commit them to be tried by the courts and sent to prison. That's where laojiao came in, viewed by its defenders as a solution to a social malaise that many believed was a byproduct of an increasingly commercialized society.

"From its very beginning, laojiao was the closely guarded turf of the police, which issued the orders, but under the name of a local laojiao committee. How could the right to issue such an order be given to the same men who turned up at people's doors and took them away?" asked Song. "Realizing the consequent abuse of power, the central government sought to alleviate the situation by introducing judicial reviews and legal counsel, which in reality were often denied to laojiao detainees."

Another contradiction, according to Zhou, was that laojiao detainees, who by definition are not criminals, were often detained for periods far longer than many criminal sentences.

"Laojiao didn't have a time limit until the 1980s. Then, it was decided that the typical sentence would be one to three years, with the possibility of a one-year extension. Keeping in mind that the minimum criminal sentence is one month, that arrangement appears illogical, even absurd," he said. "Little wonder I have met people undergoing re-education punishment but begged to be convicted and sent to prison."

It's estimated that 310 laojiao were in operation in 2007, and in April that year, a group of leading scholars drafted an open letter calling for the abolition of the system.

In the years that followed, the calls gained momentum as laojiao became entangled with another hotly debated policy - xinfang, or "letters and calls", a nationwide form of petitioning through which a person can take his grievances to xinfang bureaus from the local level all the way up to the head office in Beijing.

"Xinfang has always been there, since 1949. But in the past 15 years, it has started to gain widespread public attention, because the sheer amount of controversy it generated seems to have overshadowed its original goal," said Wei Rujiu, a lawyer in Beijing. "When the government first shifted its emphasis toward xinfang, in the early 1990s, it was to check the conduct of local governments and improve the transparency of legal proceedings at local courts. However, since all decisions made by xinfang bureaus are basically administrative ones, the policy has unintentionally weakened the authority of court rulings."

A chain reaction occurred: Knowing that court rulings are often subject to challenges, dissatisfied parties in a legal case would then engage in a seemingly endless process of petitioning, working from the lowest to the highest authorities. In desperation, some went on hunger strike or laid siege to xinfang bureaus and their personnel.

Besieged by petitioners, the State Bureau for Letters and Calls called on local governments to keep the trouble within their own territories. Officials who failed to do so were marked down in their annual appraisals, so they instigated measures to prevent people from traveling and making their cases in Beijing, a practice known as "intercepting".

"It would be an exaggeration to say that repeat petitioners accounted for the bulk of laojiao detainees in recent years, but some of them were indeed thrown into the camps by their local government to be 're-educated,'" said Wei. "In the worst cases, laojiao was used to stop people petitioning against local governments in relocation or land condemnation lawsuits. That emboldened some local officials to gain revenge without the law entering the equation."

One high-profile 2006 case involved a woman from Yongzhou in Hunan province, whose 11-year-old daughter had been gang-raped and forced into prostitution. Two of the six men convicted were given the death sentence and two were jailed for life. The other two were sentenced to 15 and 16 years. Dissatisfied and determined to pursue the death penalty for all six men, the woman began petitioning the local xinfang. However, when she took her case to Beijing, the local authorities became involved. In August 2012, the mother was given a laojiao sentence of 18 months, but only served nine days because of the intensive, sympathetic media coverage of the case. She sued the local laojiao committee, and a high court ruled in her favor in July this year, just four months before the CPC Central Committee announced the abolition of the system.

"That mother not only won her case, she helped to expedite the demise of laojiao by fixing national attention on the issue and turning a no-go area into the hottest Internet search word," said Wei.

Uruguay becomes 1st nation to legalize marijuana

Uruguay becomes 1st nation to legalize marijuana

Snowstorm blasts US

Snowstorm blasts US

2013 Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm

2013 Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm

Reuters images of the year - politics

Reuters images of the year - politics

Conjoined babies waiting for surgery

Conjoined babies waiting for surgery

Chinese say their goodbyes

Chinese say their goodbyes

Obama shakes hands with Cuban president Castro

Obama shakes hands with Cuban president Castro

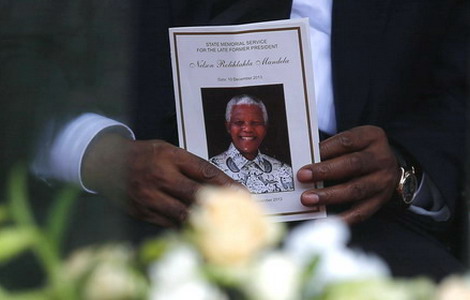

S Africa holds memorial service for Mandela

S Africa holds memorial service for Mandela

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Handshake could signal improving ties

US Congress negotiators reach budget deal

Retirees saddled with kids' costs

Bar lowered for private pilots

Building impact reports will be released

Obama urges Congress to pass budget deal

Beijing announces theme, priorities of APEC

Battle against counterfeit goods enters a new phase

US Weekly

|

|