Race to remember story of resistance

Updated: 2014-04-28 07:50

By Andrea Deng (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

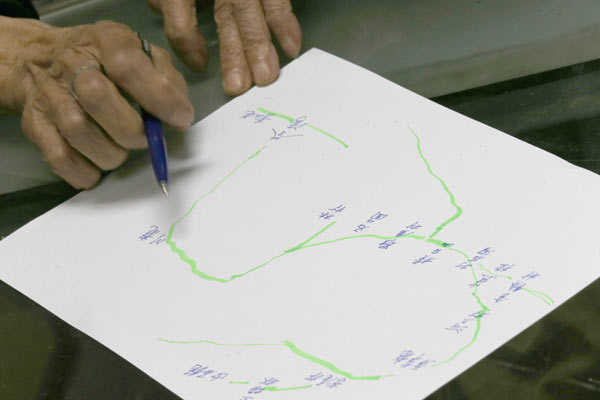

| Liu Chun-sing recalls his role in devising one of the paths along which hundreds of prominent scholars and politicians were able to flee Hong Kong. EDMOND TANG / CHINA DAILY |

Last stand

The Hong Kong Kowloon Brigade was the only resistance force in Hong Kong during the Japanese Occupation between Dec 25, 1941 and Aug 15, 1945, said Liu Shuyong, deputy director of the Hong Kong Local Records Office at Lingnan University.

Chan Sui-jeung, an honorary research fellow of the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Hong Kong, said most members of the HK-Kowloon Brigade were local people - farmers, fishermen, sometimes 12-year-olds or 17-year-olds who joined the force because they had seen enough of the inhumane acts committed by the Japanese.

Many of the Hong Kong Kowloon Brigade members who survived the war have died in the intervening years, while those who remain are in their 80s and 90s.

Historians have noted the lack of historical material about the brigade. Liu Shuyong said that to examine the brigade and its related history, one must rely on oral history, the memories of the fighters who lived that history.

|

Resisting the invaders "The brigade had limited military success against the Japanese during the occupation," said Chan Sui-jeung, whose book about the Hong Kong Kowloon Brigade has been widely cited. "The reason they chose guerrilla tactics in Hong Kong is that any head-to-head battle with the Japanese army would be certain to end in defeat. The Japanese had better weapons. Guerrilla warfare was the best way to contain them," said Chan. Chan's book also told the story of Captain Ronald Homes of the British Army Aid Group. Homes had been sent to Hong Kong during the early stage of the occupation to carry out secret investigations - primarily, how to rescue British captives from the Japanese. When he visited the brigade in Sai Kung, he found its members were poorly armed. Their weapons were primarily guns that had been left lying in the field after the Battle of Hong Kong. Nonetheless, the guerrilla forces in Sai Kung alone numbered about 1,000 by 1942 and probably continued growing after that, though the men were short of armaments. Kwong Chi-man, a research assistant professor of the History Department of Hong Kong Baptist University, found several instances in Japanese records of guerrilla attacks in and around Hong Kong during the occupation. The attacks were carried out both by Communist-led and Kuomintang-led guerrilla forces. The Japanese tried repeatedly to root out guerrilla positions in Hong Kong, but never succeeded. The guerrillas always managed to withdraw and vanish into the wilderness, according to Kwong. "The small number of cases (mentioned in Japanese records) indicates that sabotage and attack were probably not the main roles of the brigade during the war. The more important role was to support the Allies - particularly the BAAG - to collect useful information about Japanese military activity in the area and to rescue important figures and military personnel," Kwong said. Liu Shuyong, deputy director of the Hong Kong Local Records Office of Lingnan University, said that as a guerrilla force, the brigade was successful in containing the Japanese army. He gave an example: Toward the end of the occupation when the guerrilla forces had grown to number about 5,000, they blew up the number four bridge on Waterloo Road in Mong Kok, close to the gendarmerie's base. The Japanese, who were trying to sweep the New Territories at the time, had to return to Kowloon to ensure that their military base was guarded. In early 1944, the guerillas bombed the Kai Tak airport. Liu cited other instances where the brigade's musket branch in Sha Tin staged successful attacks against the Japanese in places such as Lion Rock, Cha Kwo Ling, Ngau Chi Wan and Long Harbour. By Andrea Deng |

As next year's 70th anniversary of China's victory in the war against the Japanese approaches, historians and local residents are rediscovering the history of the shadowy group whose members were Hong Kong's only defenders during the occupation.

During this year's annual meetings of the National People's Congress and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, Chan Yung, an NPC deputy from Hong Kong, proposed that more events be held to promote greater awareness of those who fought for Hong Kong following the Japanese landing on Dec 7, 1941, the same day Pearl Harbor was bombed.

Chan Sui-jeung accompanied a number of HKU students as they interviewed former Brigade members. The Hong Kong East River Column History Research Council, which was formed in 2008, made contact with the family of Yin Linping, a prominent member of the column who rescued a US pilot during the war. The story later became the subject of a book written by a member of Yin's family. Other historians, including Lingnan University's Liu Shuyong, have also published papers about the brigade.

Threat of persecution

The Hong Kong Kowloon Brigade was credited with rescuing more than 800 prominent citizens, among them scholars, artists, military officers and political leaders, who opposed the Japanese occupation. Soon after the British Army surrendered, the Japanese ordered all leading patriots who had opposed the invasion to surrender, or be hunted down and killed.

Shen Dehong, a leading Chinese writer under the pen name of Mao Dun, wrote a memoir about his rescue by brigade members. In a book written by Chan Sui-jeung, Shen recounted how the guerrillas had to work closely with triads to bring those under threat of persecution and death to safety. The members of the criminal underworld "were most knowledgeable about the safest escape routes and the best means of evading the Japanese".

Shen added that the gangsters normally collected protection money for their assistance, but not from those under the protection of the guerrillas, possibly out of respect, or because they were in awe of the brigade's "superior weaponry and organization".

"The rescues in the urban areas under Japanese control took place at night," Chan Sui-jeung told China Daily. "We're talking about (the brigade) rescuing nearly 800 important people over a period of six or seven months. It was not easy, considering that a lot of these important politicians and scholars were quite old at the time. Climbing up the mountains in the New Territories was not easy. Brigade members had to take care of the escapees' luggage and feed them."

Chan Sui-jeung, who has been a Sai Kung district officer since 1980, wrote his book in 2009. Because Sai Kung was one of the strongholds of the Hong Kong guerrillas, he was able to hear the stories of former guerrillas and began gathering materials for his book in 1983.

Brigade members told him that the New Territories were crawling with triad members and other bandits. "The guerrillas killed the bandits, as well as the traitors. Cheung Hing, for example, was a native of Tai Long, Sai Kung. He killed many traitors. He killed many Japanese too," Chan Sui-jeung said.

"They had done it (maintain order) so well that when the British came back to Hong Kong after Japan surrendered, they invited brigade members to serve as a defense force in the countryside until 1946," he added.

Today, Liu Chun-sing, the former brigade member, works as a volunteer for the East River Column Hong Kong Kowloon Brigade Veterans' Association. He helps primary school students and historical researchers to understand the history of Hong Kong during the Japanese occupation.

Contact the writer at andrea@chinadailyhk.com

Obama roasts himself, rivals at dinner

Obama roasts himself, rivals at dinner

Forum trends: No house, no marriage?

Forum trends: No house, no marriage?

Huge mist cannons attract people in Lanzhou

Huge mist cannons attract people in Lanzhou

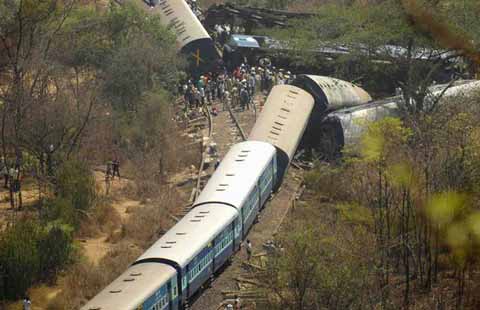

Indian train derailment kills at least 12

Indian train derailment kills at least 12

One handed climber scales UK's toughest routes

One handed climber scales UK's toughest routes

World leaders when they were younger

World leaders when they were younger

H&M promotes summer collections with DJ show

H&M promotes summer collections with DJ show

Getting a taste for the World Cup

Getting a taste for the World Cup

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Travel passes to DPRK made easier

Yunnan's only panda perking up thanks to TV

Intl cooperation to aid drug fight

Deal signed to upgrade roads, grid in Ethiopia

China busts foreign spy ring

Tokyo lawmakers begin China visit

Houston tries shuttlecock diplomacy

Senior Chongqing official investigated

US Weekly

|

|