A Lethal Harvest

Updated: 2016-04-08 10:28

By Chris Davis(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

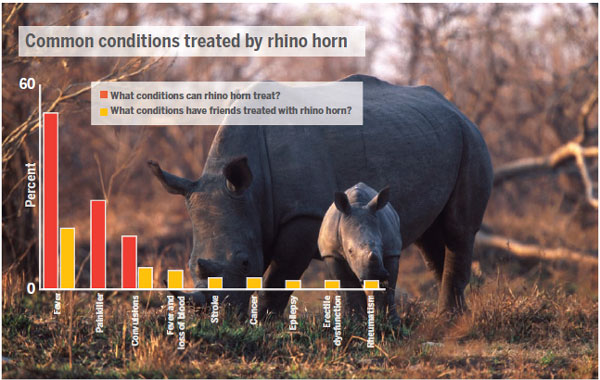

A white rhino calf stands beside its grazing mother in Kruger National Park. courtesy of IFAW / J. hrusa |

Thanks to unabated demand for its horn in Asia, the African rhinoceros is teetering on the verge of extinction. There are some ideas for saving them that go beyond stopping poachers, Chris Davis reports from New York.

C runch the numbers any way you want, but the endangered African rhinoceros is at a tipping point. More are poached each year than are being born. All 5,000 wild black rhino could be gone in 10 years; all wild rhinos - including the 15,000 whites in South Africa - by 2036, experts say.

A record 1,338 were slaughtered for their horns in 2015. That's up from one the year before 2007, when there were 13 taken; 111 in 2008; 333 in 2009; 448 the next year. That's a 40 percent-a-year rise.

The numbers have marched upward steadily in tandem with elephant ivory. The reasons are plain. People who traffic ivory also traffic rhino horn. The routes and techniques to smuggle the two commodities to consumers are similar - as are the consumers.

While there has been a steady push on enforcement, small underpowered governments can't keep up with what has become a robust and deadly criminal enterprise.

There have been a few creative ideas put forward to save the rhino, from the high-tech - one startup, Pembient, is trying to "biofabricate" artificial rhino horn - to good old fashioned free market economics.

The question is: Can any of it be done in time?

The conventional tendency is to point to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) as the main culprit on the demand end for rhino horn and simply say if people stopped using it, the poaching would stop.

There is a precedent for such an approach, as Harry Peachey of Conservation Messaging LLC explained. Between 1970 and 1990, the black rhino population in Africa had dwindled down 98 percent - the largest recorded decline in modern history of any large mammal - all from poaching.

The primary consumer was Taiwan. Go into any TCM pharmacy there at the time and the pharmacist would typically have a rhino horn on a spindle, scrape off the customer's order and wrap it up.

In the early 1990s, a delegation from the UN went to Taiwan on what was ostensibly a consumer survey and ended up teaching more than they learned. They asked people if they used rhino horn. The vast majority said yes they did. Did they know that it was moving rhinos to extinction? No, they did not. Was that a matter of concern to them? Yes it was, most said.

"That could have been a very pure response, it could have been because they wanted rhinos to remain extant so they could have access to rhino horn for the rest of their lives," Peachey said, "but regardless the vast majority were concerned and as a result they turned away from rhino horn and went to other medicines. It had an effect on poaching and at the time rhino poaching became almost a non-issue."

Black rhino

The black rhino population got a chance to recover, from less than 2,000 to more than 5,000 today.

Moving into the 20th century, the black rhinos' cousins to the south, white rhinos, were the ones who needed help. Their numbers had plummeted perilously to less than 50, perhaps to 20. South Africans took them onto reserves and protected them, watching over them and protecting them, thanks to which there are now more than 20,000, a huge recovery and success story.

South Africa now has 80 percent of Africa's remaining rhinos and 25 percent of those are privately owned on ranches and reserves. But they are all under siege.

"With this increasing demand for rhino horn the tables are starting to turn," Peachey said. "Most of the rhinos that are poached now are southern Whites, but any rhino with a horn is vulnerable."

The heaviest demand is coming from Vietnam, he said, where it is being given as gifts and bribes to curry political favor. "Rather than consuming it a few grams at a time, rhino horn there has become a status symbol, consuming more in one event than you would under more traditional circumstances use in an entire lifetime. And there are people who did this two or three times and the value of horn has escalated incredibly."

To address the crisis, South Africa put together a panel of experts last year to explore the idea of creating a legalized international market in rhino horn trade, something the rhino ranchers are obviously in favor of. The problem for the panel was there was practically no literature - studies, surveys, data, analysis - of the market.

Enter the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). "We were hearing about a proposal that South Africa was looking at to legalize an international trade," said NRDC researcher Alex Kennaugh. "We wanted to look at the data to see if the economics stacked up. And found that there was no good statistically significant data about what the demand looked like."

The South Africans pushing for the market reckoned they could supply the demand and if they couldn't then the model fell apart, Kennaugh said.

"They basically said we'll flood the market, the price will drop, it will alleviate poaching pressures. But if you can't supply the market, then of course that doesn't hold water."

The numbers being used to make the case didn't sit right with Kennaugh. "We decided it might be better to get some harder numbers," she said. "Something we could really start to draw what the demand looked like, get a sense of the scale and get an idea of why consumers want to purchase it."

Then nations could begin to design what conservationists call "demand reduction strategies". Or actually say, Yeah, you can supply the market; maybe this is a good solution to the poaching problem.

The South Africans' proposed supply of horn was a mixture from natural mortality and harvesting from privately-owned herds. "The thought was private individuals could have rhino farms and non-lethally shave or cut the horn off and supply the market - a non-lethal solution to supply the demand. They grow back at a slower rate - 1 kg a year once they start cutting it," said Kennaugh.

"So you have to wait until the rhino is about 6-years-old and they have a life span of 36 years. So you can shave off one kilo every year for the life of the animal. South Africa has a long tradition of using wildlife as a commodity to generate revenue."

Slogans for family planning need to be updated

Slogans for family planning need to be updated

26,000 Kung Fu students form huge patterns

26,000 Kung Fu students form huge patterns

Chinese arts prove popular in Hong Kong spring sales

Chinese arts prove popular in Hong Kong spring sales

Reindeer Herders Day celebrated in northern Russia

Reindeer Herders Day celebrated in northern Russia

World's major tech companies step into the VR world

World's major tech companies step into the VR world

Skilled man gives new life to antiques

Skilled man gives new life to antiques

Top five car-hailing apps in Chinese mainland

Top five car-hailing apps in Chinese mainland

Shanghai builds 'Deep Pit Hotel' upon a former mine

Shanghai builds 'Deep Pit Hotel' upon a former mine

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Marriott unlikely to top Anbang offer for Starwood: Observers

Chinese biopharma debuts on Nasdaq

What ends Jeb Bush's White House hopes

Investigation for Nicolas's campaign

Will US-ASEAN meeting be good for region?

Accentuate the positive in Sino-US relations

Dangerous games on peninsula will have no winner

National Art Museum showing 400 puppets in new exhibition

US Weekly

|

|