Pasture way of treating guests

By Erik Nilsson In Ili, Xinjiang ( China Daily ) Updated: 2015-06-06 08:05:39

|

|

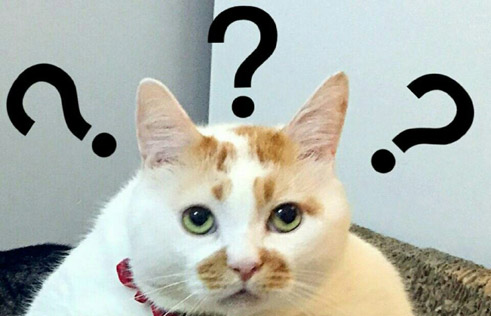

Huan Sezdehan (right) helps his son to tie a sheep to the motorbike. The sheep will be slaughtered to treat family guests. [Photo By Erik Nilsson / China Daily] |

I knew better before my second meal served among nomads and instead dabbed my palms dry with a towel.

We'd insisted against Huan's family slaughtering the sheep. Still, he and his 22-year-old son, Nursuntan Huan, cornered the creature, lashed it to his motorcycle and zipped out of sight across the prairie.

A sheep is worth about $160 - a sixth of the household's annual income. In the end, the creature bleated louder than our protests.

That's the exalting hospitality of the nomadic Ili Kazak autonomous prefecture's Zhaosu county.

The boy playfully swished the disembodied hoof through the air like a wand, squished gobs of meat between his fingers and gnawed at the pelt with a pair of pliers while his father carved up the carcass. I thought about the herders' relationship with food and the animals that provide it - that are it.

I've rarely seen my food breathe. They rarely don't see theirs breathe.

Ili's nomads' lives revolve around their livestock.

It's a place where animals not only provide sustenance but also entertainment. People hunt with eagles, play a version of polo with decapitated sheep and stage horseraces for fun.

Zhaosu's children start riding horses at age 5.

The typically scattered drifters congregate on isolated knolls on weekends to hold horseraces. Only boys ages 8 to 12 compete. Their nimbleness injects speed into the steeds.

We watched a 12-year-old's mount eject him mid-race. He got up, wiping onto his sleeve blood that oozed from his nose and lip.

A winner of that day's competition explained that parents check on the horse first if an accident happens when a child is riding.

The herders care more for sick sheep than healthy human family members - kin literally take a back seat if the family owns a truck - and mourn flocks' miscarriages.

Ili's livestock roam seasonal lanes on certain roads and bridges.

Its epic migration of tens of thousands of animals and thousands of people from winter to spring pastures is peak season for traffic police.

I photographed a policeman smooching a premature lamb on the lips as he stretched out on the grassland. (The little critter initiated.)

"Places with lots of sheep are different from places with lots of people," he says.

"Sheep listen to instructions. People don't."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face