|

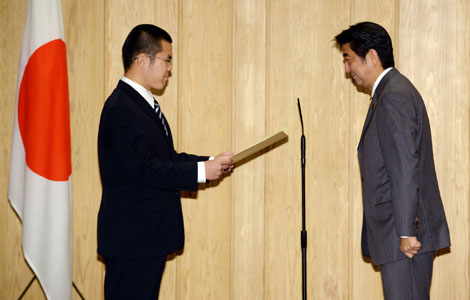

Wang Hao has achieved success not only through hard work, but with some luck as well. Cecily Liu / China Daily |

Career of China's chess grandmaster moves easily across the board

In the game of life, some may have wondered if the career of China's top chess player Wang Hao had come to a stalemate of sorts. It has been a good seven years since he achieved the ultimate and became a grandmaster as a 16-year-old, following a series of international tournament wins. Perhaps those thousands of hours' practice as a child and teen, and the seriousness and intensity of tournaments, had taken their toll. Worse, perhaps he had become bored with the board.

Not a bit of it. Over the past few years Wang has been steadily climbing the World Chess Federation rankings and is now 15th.

Either he is playing to deceive or, more likely, has settled into a more relaxed frame of mind, enjoying life as a student.

His more laid-back attitude came into play in London this month at the first of the federation's Grand Prix series world championship qualifiers in which a dozen leading grandmasters took on one another.

Wang ended up mid-table with one win, nine draws and a loss - proving how little separates the top players.

But Wang has always played down his success.

"I think I don't have a competitive personality because I'm quite lazy," he jokes.

"A game is just a game. If I lose it, I don't lose everything in my life. So I feel there is nothing to be sad about losing.

"Everyone has talent in some field, and mine happens to be in chess," he says, adding that he believes it is important to keep up with all his other hobbies, which include swimming, running, traveling, reading, watching movies and going out with friends.

"I think it's important to do things that I enjoy, and sometimes they help me play chess better, although I'm not quite sure how."

And despite bags of natural talent and years of practice, a lot is down to luck. It was by chance that he took up chess in the first place.

When he was 6, and living in Harbin, capital of Heilongjiang province in Northeast China, his parents took him to learn xiang qi or Chinese chess, a much more popular game in China. But the teacher was absent for the first lesson.

"The chess teacher next door came and asked if I wanted to give chess a try instead. The teacher told me that I could go traveling overseas if I learned chess, but I didn't believe it at the time."

Wang's early virtuosity and hard work gained him an opportunity to train full time at the National Chess Center in Beijing when he was 10. But he declined, as he disliked the secluded environment of the center and the routine training sessions.

The offer was repeated a few years later, and this time he accepted, moving to Beijing, where he spent five to six hours training each day until he went to university.

"My parents gave me a lot of support for chess. They moved to Beijing, partly to look after me."

In 2002 Wang became a member of China's youth chess team, and in 2004 he was admitted to the national team and went on to compete in the Chess Olympiad and other international tournaments.

But it was winning the Dubai Open in 2005 that he enjoyed the most.

"Many of my opponents underestimated my abilities as I looked very young back then. I was lucky."

However, winning the Dato Arthur Tan Malaysian Open and becoming a grandmaster the same year had nothing to do with luck.

Now, Wang fits in his chess touring commitments with his studies at Peking University, where he is in the third year of a degree course in advertising.

The Grand Prix tournament in London this month proved especially significant for him - and to the game as a whole.

The federation had just sold the commercial rights to chess to the US media mogul Andrew Paulson, who aims to widen exposure and popularize chess further through live broadcasts of games.

"I think Paulson's plans are quite normal as a commercial transaction," Wang says. "If he can make chess more popular and earn money at the same time, then there is nothing to be said against it."

Paulson also pledged to move the tournament rounds from remote towns to major cities, with Paris and Berlin on the board after London.

"I think holding the competition in big cities is great," Wang says. "I've been to many remote towns for tournaments where there is nothing to do. It can be depressing."

He greatly enjoyed playing at the London venue, the austere Simpson's-in-the-Strand restaurant, an old chess house where an encounter in 1851 between a German and a French grandmaster went down in chess history as the "immortal game".

He also made the best of London's better-known tourist attractions, such as the National Gallery and Westminster Abbey, on rest days. "London has a great cultural atmosphere," Wang says, and chess, he adds, is like a work of art.

"A game of chess can be so creative and so subjective that I don't quite know how to describe my feelings."

He is equally unsure about some of Paulson's other plans for chess. As with major snooker tournaments, chess games will be presented with live commentary. And, unlike snooker, biometric measuring devices will monitor players' pulse rates, blood pressure and sweat levels.

It is the live commentary that Wang finds "a bit scary".

"If I get too tired, the commentator may say, 'This guy is about to fall asleep' in front of all this audience, and it's quite embarrassing."

Given his relaxed approach to competition, he does not mind the biometric measurements too much. It would have been interesting to see how he measured up in London, where he arrived just a day before the tournament. He said he felt slightly jet-lagged for the first few games.

"I didn't have time to prepare much, so I'm happy with my scores. But I'm used to it now, as I often fly to far-away tournaments feeling jetlagged. I could have come a few days earlier, but I didn't want to miss too many university lessons."

The London Grand Prix had prize money of 166,000 euros ($215,000), which is distributed according to player rankings.

Chess has gained popularity in China in only the past few decades and still trails Chinese chess and Go by a considerable margin. There are about 3 million chess players in China compared with many more million Go players, according to a 2008 article on Chessbase, a chess website.

"Very few people played chess when I first started learning it, but nowadays it is becoming more popular," he says.

"I think it is still difficult for chess to become mainstream in China the way it is in Europe, as Chinese chess is already a part of the Chinese culture."

Wang is not sure that he will become a professional chess player.

"I still need to think about what I want to do after I graduate from university. But whatever I do, I want a life with lots of freedom."

cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 10/19/2012 page28)