The enigma that was 'Vinegar Joe'

By Zhao Xu (China Daily) Updated: 2015-02-27 07:34A tough assignment

|

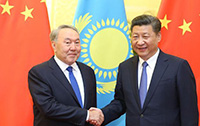

General Stilwell poses with a Chinese soldier in the China-B Theater during WWII. Provided to China Daily |

The "difference between this outward expression and the notes which he kept in his own hand", as the elder Easterbrook called it, may always be open to interpretation. However, when Stilwell accepted the job of leading the US Army in the CBI in early 1942, Henry Stimson, the US secretary of war between 1940 and 1945, accepted that he had been given "one of the most difficult" assignments of any theater commander.

John Easterbrook believes that his grandfather would have accepted the situation without complaint: "Compared with the 'main' battlegrounds in Europe and Africa, the CBI theater was severely lacking in resources, both men and equipment, but my grandfather believed a soldier's duty was to accept assignments for the good of his country."

Stilwell arrived in Burma, present-day Myanmar, shortly before the country fell to the Japanese. The Allied defeat resulted in the closure of the "Burma Road", which severed China's supply routes on land and sea, and forced Stilwell to lead a party of more than 100 through the jungle on foot to Assam in India, marching at what became known as the "Stilwell Stride", 105 paces per minute.

Calling the retreat "humiliating as hell", Stilwell, who was also chief of staff to Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Army, later led the 1944 campaign in the north of the country that laid the foundation for the Japanese defeat in China.

For John Easterbrook, that hard-won success can be traced in part to Stilwell's long association with China and her people.

"Before his CBI mission, my grandfather had been to China three times. His first stay was between 1920 and 1923, and he was the US Army's first Chinese-language student," the 74-year-old said, referring to Stilwell's fluency in spoken and written Chinese

During his first visit, Stilwell used the engineering skills he'd acquired at West Point Military Academy to work as chief engineer on the construction of a famine-relief road in Shanxi Province. "Working and living with laobaixing ("the old 100 names" or "ordinary people") on the road gave him profound knowledge of the Chinese people," said John Easterbrook, who added that his grandfather returned to China in 1926, staying three years, and then lived in the country again from 1935 to 1939.

In July 1937, fighting broke out between the Chinese Nationalist Army, stationed at the Marco Polo Bridge (aka Lugou Bridge) in the southwestern suburbs of Beijing, and the Imperial Japanese Army. "The Lugou Incident", as it became known, marked the start of China's eight-year war against the Japanese.

"At that point, the United States was still neutral. As a military attache in the US delegation to Beijing, it was my grandfather's job to gather intelligence. So he was out observing both forces - not easy, as he was guarded by both," said John Easterbrook, who believes Stilwell's faith in the Chinese soldiers, rather than his familiarity with "Japanese weaknesses" - convinced him that his forces would prevail in the CBI.

In a speech delivered in 1942 on the fifth anniversary of the Lugou Incident, Stilwell said: "To me, the Chinese soldier best exemplifies the greatness of the Chinese people - their indomitable spirit, their uncomplaining loyalty, their honesty of purpose, their steadfast perseverance ..."

In April 1942, he founded a training center for Chinese soldiers in Ramgarh, India, where he was later joined by Ernest Easterbrook. During the northern Burma campaign in 1944, Stilwell set a precedent by instituting compensation and a rehabilitation program to help the families of dead or seriously wounded Chinese troops.