Cameras and carbines capture life during wartime

By Zhao Xu (China Daily) Updated: 2015-07-30 07:57

|

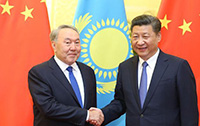

Sydney Greenberg with Chinese youths in Yunnan province in 1944. Photo Provided to China Daily |

Although the US troops generally acclimatized well, there were some things they couldn't endure. Adding a snake or rodent to the menu of endless bowls of rice may have filled Sydney Greenberg's stomach, but drinking untreated ditchwater left him with malaria and dysentery, which reduced his body weight by half.

The hardships didn't stop him from opening his mind - and heart - to the Chinese people, though. Having been taught what he called "Chinese decorum" (appropriate behavior) on the voyage, the soldier/photographer discovered a "secret weapon" - cigarettes.

"My mom, who worked in a supply outfit at home, would send dad packs of cigarettes," Philip Greenberg said. After he handed out the cigarettes to the locals, the elder Greenberg was rewarded with a new level of access and intimacy, and his subjects - such as a happy mother and her beaming infant daughter - appear totally unguarded and at ease.

In one of Greenberg's best-known photos, a gun-toting Chinese soldier is depicted from behind as he stands on top of a tank in the monsoon season, watching as a US air force plane appears out of the clouds, dropping food for the Allies. While the leaden sky and heavy, low-hanging clouds conjure up an apocalyptic atmosphere, the towering image of the soldier appears as a beacon of hope and a powerful symbol of resistance.

Although, the heavy equipment and safety concerns - the photographers were usually guarded by Chinese soldiers - often prevented the team from shooting or filming on the front line, the photo company also had other, less deadly enemies.

"Hedge's 35mm Kodak has a case of termites today," Sydney Greenberg wrote in his diary, with reference to Arthur Hedge, a fellow cameraman. "Seems he hung his camera on a tree and a mother termite - pregnant, of course - got into the opening above the lens. This afternoon, while taking pictures, he discovered a million termites running all over the box; so we spent the latter part of the afternoon smoking them out."

On the same day, he wrote: "At night, I put the camera in a gas cape and put the whole package in the musette bag, but in the morning I have a nice batch of green mold all over the camera and even inside the lens board."

The photos were sent to primitive laboratories, mud buildings where chemicals were weighed on aged scales borrowed from drugstores, for overnight developing and printing.

When the soldiers were not out snapping their shutters right and left, they "sat in dugout trenches and watched the bursts of hand grenades", as Sydney Greenberg described it, recording what they saw in their mind's eye. "It's almost like a motion picture. Flares light up the sky; red, blue, and green, then a white one," he wrote in his diary. "The major tells us that the first three Jap strong-points are ours."

On Sept 9, 1945, the Japanese army officially surrendered to the Chinese army in Nanjing, then known as Nanking.

The war was over, and Sydney Greenberg was on hand to capture the jubilation on film. "While in Nanking, my dad was given two options: he could fly to Shanghai and from there go back to the States by ship; or, he could go to Kunming, the city of his arrival, and then go to India, where he would board a ship," Philip Greenberg said. "Dad chose to honor the memory of his arrival."