COVID-19 widening education gaps

By ARUNAVA DAS in Kolkata, India | China Daily | Updated: 2021-09-21 08:28

Writing out the English alphabet is supposed to be a simple task for most 10-year olds in India. But for Vandana Mistri (name changed on request), it is turning out to be a daunting challenge. Meanwhile, some of her former classmates are faring even worse, as they are unable to even identify many of letters.

This is happening because it has been a year and a half since Mistri and the other schoolchildren have attended a class.

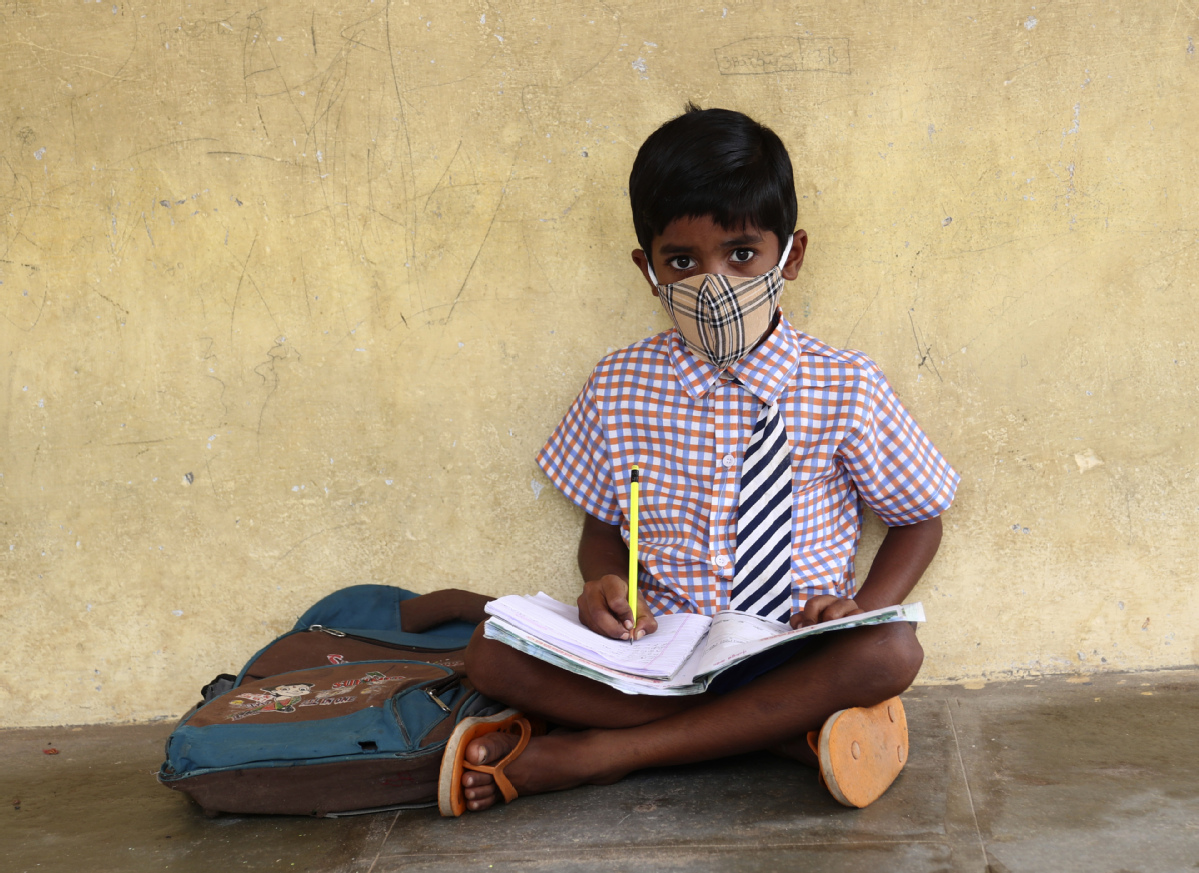

Mistri and her friends are among the hundreds of thousands of poor or rural kids that have been cut off from education amid COVID-related school shutdowns in India.

A few schools and their students switched to online classes when the country went into lockdown last year to curb the spread of the virus.

But many government-run schools have been unable to cope, leaving kids like Mistri falling behind in primary education.

The digital divide is accelerating inequalities, according to a report by Learning Spiral, one of India's leading online examination solution providers.

The major challenge of remote learning is the disparity in access-from electricity and internet connections to devices such as computers or smartphones, according to Manish Mohta, managing director of Learning Spiral.

More than 50 percent of Indian students, including those from both urban and rural areas, do not have access to the internet for online studies, Mohta added.

A joint report by UNICEF and the International Telecommunication Union said that children from poor households in lower-income regions are falling further behind their peers. Only 24 percent of Indian households have the internet and are able to access e-learning, the joint report said.

Even in the national capital of Delhi, more than 1.6 million pupils studying in government and municipal schools do not have access to smartphones or computers.

It will take a while to assess the learning loss and the enormous impact it will have on society and economy of the country, and also social equilibrium, said Satyam Roychowdhury, managing director of Techno India Group, an educational business conglomerate.

A survey carried out by a renowned India-based economist, Jean Dreze, found that out of 36 children enrolled at the primary level, 30 were not able to read a single word.

A recent study from Bangalore-based Azim Premji University said the school closures have already had negative implications. It has resulted in a complete disconnect from education for the vast majority of children or inadequate alternatives like community-based classes or poor alternatives in the form of online education, including mobile phone-based learning.

"One full academic year is gone, but what is alarming is the widespread phenomenon of 'forgetting' by students of learning from the previous class. Being out of school for long means that children not only stop learning new things, they also forget some of what they have learned," the study pointed out.

A report from the National Sample Survey Office, an entity under the country's Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, has said 32 million children had been out of school before the pandemic broke out.

"The number will double in a year's time. Only a third of 320 million schoolchildren are pursuing education online," Roychowdhury of Techno India Group said.

According to the Azim Premji University study, 67 percent of children in Grade Two, 76 percent in Grade Three, 85 percent in Grade Four, 89 percent in Grade Five, and 89 percent in Grade Six have lost at least one specific ability from the previous year, and 82 percent of children on an average have lost at least one specific mathematical ability from the previous year.

Osama Manzar, founder and director of Delhi-based nonprofit organization Digital Empowerment Foundation, pointed to serious setbacks for girls in particular."COVID-19 has highlighted the deep cesspool of the digital exclusion of girls," he said.

The story is all about disconnection and lack of access, and the looming risk of millions of students disappearing from the mainstream of education, and in larger context, society in the long run.

Partha Banerjee, a New York-based activist and educator, said this is high time civil society created its own educational platforms, and took advantage of technology to fill in the educational gaps.

In India, many people and organizations are trying to do it, Banerjee said. But their challenges are enormous, especially because powerful political parties and their media do not want civil society to empower themselves.

"But in the long run, if you think about the academic, social and environmental devastations, this is perhaps the only way to get out of partisan politics," he said.

The writer is a freelance journalist for China Daily.