hotrecommend

Echoes of Chinese culture

By Xie Yu (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-05-05 06:48

|

Large Medium Small |

Taiwan man strives to keep connection with ancestral past

BEIJING - Forty years ago, all young Taiwan man Huang Yuangsung knew about the Chinese mainland came from the memory of elders.

As the eighth generation of a group of Hakka people who moved to Taiwan over 200 years ago, Huang was curious, keen to know about the origins of all the complicated folk customs, delicate tastes of countless Chinese dishes and the long, bewildering rituals.

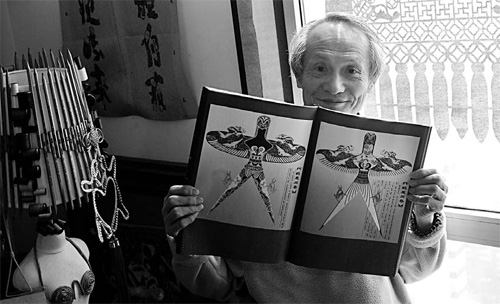

Huang Yuangsung, a well-known Taiwan publisher, holds a copy of Echo magazine he and his friends launched nearly 40 years ago. [China Daily] |

But at that time it was impossible for him to cross the Straits. The civil war had split the two sides in 1949, and the tension in cross-Straits relations lasted for decades.

So his only impressions about the Chinese mainland came from mainland-produced products sold in Hong Kong.

"You could never imagine how excited I was when I saw those things," Huang said.

Everything from Yantai apples, dried fish fillets from Dalian and liquor from Shanxi to blueprint cloth from Nantong seemed so strange but so familiar, echoing with the glittering descriptions stored in the depths of his memory.

But it was crucial to cut off the "Made in Nantong, China" label from the blueprint cloth before returning to Taiwan, or it might cause him trouble.

In 1971, Huang and his friend Wu Meiyun launched a magazine to promote Chinese traditional food, clothing, homes and modes of travel.

"I started editing Echo at that time. In order to collect more firsthand information about the mainland, I often traveled to Hong Kong," Huang said.

"We have such a glamorous culture, yet no one knew it and there were few Chinese people who recognized the significance of protecting our valuable cultural legacy," Huang said.

So they started.

Huang's magazines were published in English at first, as their target readers were foreigners. As they gradually expanded, they shifted the magazine to a Chinese version - Hansheng, literally Chinese Voice - as more regular people in Taiwan demanded to read it.

In 1988, Taiwan authorities for the first time allowed veterans to return to the mainland and visit their families. Huang accompanied his father-in-law, a former Kuomintang airman, on a trip to the mainland.

From then on, he began collecting materials on the mainland.

Huang said that in the past he would go to villages by tractor, looking for able craftsman or to measure ancient folk houses. Luckily, village roads in rural areas have improved a lot in recent years and he can now drive.

In order to rediscover the original make and shape of Beijing-style kites, he spent nine years looking for the ancient formulas and master craftsmen, then waited for the old kite expert to practice over 100 kite-making methods. The magazine's special issue on kites has been praised as "the most beautiful book" by its readers.

Today, Huang has six studios on the Chinese mainland. His studio in Beijing is packed with all kinds of collections, including clay figures from Wuxi, paper-cuts from Shaanxi, Beijing-style kites and New Year paintings from all around China.

Hansheng is also becoming more and more influential. In 2006, Hansheng was selected "Best of Asia" by Time magazine. The same year, Hangsheng's special issue, which focused on introducing wheat food into Shanxi province, won an international cooking award in Spain.

More than 80 percent of Hansheng staff members are young people. The magazine has also opened two cooperative programs with Southeast University and Tsinghua University to encourage more students to learn traditional workmanship and culture.

"Tradition is like the head, while modernization is like the feet. If the feet keep going forward, the body will split. I need to become the torso, to link the head and feet together," Huang said.