Shipping: A hard life on ocean wave

By Alfred Romann in Hong Kong ( China Daily ) Updated: 2013-05-17 09:01:00

|

|

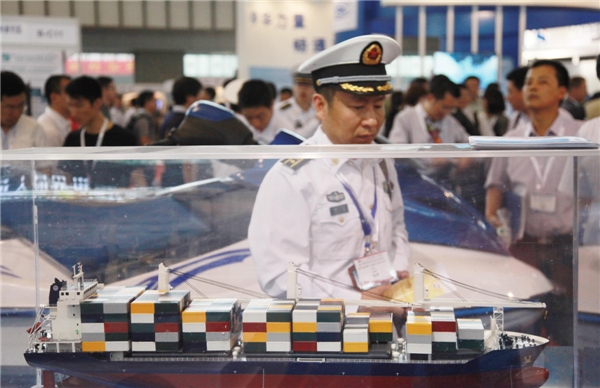

Despite the decline of the shipping industry, the Kwai Tsing container terminals in Hong Kong remain among the busiest in the world. [Photo by Er QiZheng / China Daily] |

Challenging times likely to remain until at least next year, reports Alfred Romann in Hong Kong.

After buoyant times, the shipping industry is experiencing that sinking feeling, with all hope of a bottoming out and rebirth having been smothered.

Shipowners and those who charter vessels were optimistic during the first two months of this year, but during the past couple of months the paucity of orders for new vessels has all but dashed hopes. Times are likely to remain challenging until at least next year.

"The shipping industry is at historically low levels, and it can't get much lower. If you are looking to buy ships, you couldn't find a better time. The only issue is that you would have to sustain this market for a few years before you started to make a lot of money," said Ravindranath Raghunath, head of chartering at the Noble Group. "Since 1997, the market has not been any lower than it is today."

China's largest shipping company, China COSCO Holdings, expects to report large losses for 2012, adding to significant losses in 2011. The Danish giant AP Moller-Maersk A/S has warned that global overcapacity is a threat to the industry. Dry bulk shipping rates in 2012 were a fraction of the 2010 highs and have yet to recover. All this bad news has put the industry in a funk.

Between 2003 and 2008 the mood was exuberant. They were boom years and the industry dreamed of almost perpetual expansion. Powered by economic growth in China and its seemingly inexhaustible demand for raw materials, the shipping industry reached record highs in 2008. Demand for space in container, bulk and tanker ships far outstripped supply, so owners could easily set almost whatever price they chose to hire out ships, while shipping companies could virtually set their own fees.

Massive profits pushed companies to order ships in record numbers, but those orders marked the beginning of the end of the good times. The addition of hundreds of ships to the global fleet vastly increased the supply of cargo capacity.

By itself, that increase would have imposed significant downward pressure on prices, but the industry was also hit by the global financial crisis. Economies in North America and Europe started to contract, while growth in Asia -most notably China - slowed. This translated into much lower demand at a time of increasing supply. As a result, the industry slumped.

The Baltic Dry Index, issued every day by the London-based Baltic Exchange, which tracks the cost of shipping some of the major raw materials, is at levels unseen since 1997.

The index reached a record high of 11,793 in May 2008 and then began to plummet. It fell to just 647 in February 2012. On March 22, the index was at 922, up 33 percent for the year but still at historic lows. On Thursday it opened at 861, 11 points below the previous day's close

The problem is that there are just too many ships out there, according to industry stakeholders.

"This is clearly not a demand-driven market," said Raghunath. "The next couple of years will not be about demand."

The industry had expected to see the glut in capacity sorted out this year through the trade in ore and measures taken by companies to cut supply, such as mothballing older vessels or slowing ships along their routes, thus limiting the cargo space available.

But, what actually happened surprised everybody.

"Had I made this speech two months ago, I would have said 'Things are looking good, no one is ordering ships'," said Raghunath. "What we have seen in the past two months is record orders . . . I don't recall any 60-day period in which so many Capesize ships have been ordered. Certainly not in the past four or five years."

Capesize refers to vessels too large to use the Suez canal, and which therefore have to round the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn.

Related:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Op Rana

Op Rana Berlin Fang

Berlin Fang Zhu Yuan

Zhu Yuan Huang Xiangyang

Huang Xiangyang Chen Weihua

Chen Weihua Liu Shinan

Liu Shinan