New study reveals corruption pattern

By Tang Yue, Zhang Yuchen and Wu Wencong ( China Daily ) Updated: 2013-08-22 08:02:01Many fallen officials had occupied high-level posts, report Tang Yue, Zhang Yuchen and Wu Wencong.

When the trial of Bo Xilai begins on Thursday, the event will be China's highest-profile court case for years.

Bo, the former Party chief of Chongqing and a former member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, will appear at Jinan Intermediate People's Court to face charges of accepting bribes, graft and abuse of power.

But even if he's found guilty, Bo will be just one of hundreds of officials at the level of provincial vice-governor, vice-minister or higher to have been punished for corruption and other misdeeds since the 1980s.

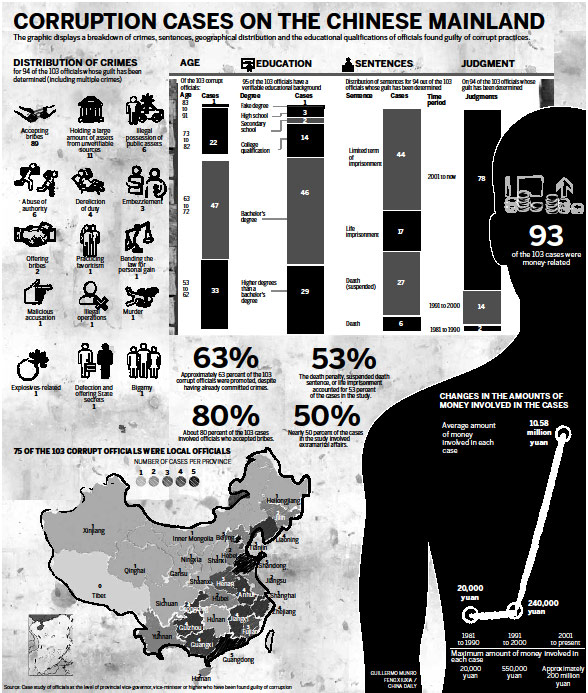

In a study on corruption that surveyed 103 fallen senior officials, Tian Guoliang, a professor at the CPC's Central Party School, has identified a pattern of criminality that reveals abuse of power in China.

Tian's findings show that corruption is climbing the ladder of power. Many of the officials exposed in recent years occupied high-level posts, while the sums involved in bribery cases have grown ever greater.

High-level officials today are also more likely than their 1980s counterparts to be involved in "collaboration" scams, where officials cooperate for mutual benefit.

The research, conducted over a two-year period, also shows that more than 63 percent of the officials were promoted despite having previously accepted bribes. The authorities were either unaware of the crimes or in some cases chose to turn a blind eye to them.

Justice was usually slow to catch up with these officials, as many committed their first crimes a decade or two ago but have only recently been exposed, according to Tian.

Unsurprisingly, most corrupt officials come from the country's better-developed regions and cities rather than poorer areas, and most operated in the financial sector, the rail network and the safety watchdogs.

"In other words, those in charge of huge amounts of public resources are more likely to be corrupt," said Tian.

Tian spoke to China Daily on Tuesday. He shared the findings of his research, and discussed the trends, motivations and character traits of corrupt officials. He also suggested a number of ways of preventing graft at all levels.

Q: What have been the main trends in corruption cases involving high-ranking officials since the 1980s?

A: On average, each case in the 1980s involved tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of yuan. But now, the average sum per case is 10 million yuan ($1.6 million). The largest involved almost 200 million yuan (Chen Tonghai, the former chairman of the State-run oil company Sinopec, was found to have accepted 195.73 million yuan in bribes. He was given the death sentence, reprieved for two-years, in 2009.)

The early cases were mainly in the field of finance, but now they have expanded to a number of sectors, including the judiciary and the system for public appointments.

In times past, corruption was usually the preserve of individuals. Nowadays large numbers of officials may be involved in each case. For example, more than 600 people were implicated in a smuggling case involving Xiamen Yuanhua Group between 1994 and 1999. More than 300 people were given prison sentences, including a former vice-minister of public security and a Party vice-secretary of Fujian province.

According to your research, some officials have dual personalities, whereby they achieve a lot but commit illegal acts. How should they be regarded by the public?

The careers of corrupt officials are not entirely bad. The officials have usually been talented and hardworking in the early years. And some displayed great aptitude for their jobs

But no matter how much they achieve, those who violate the law should be held accountable. Of course, there are those who are simply incompetent. They don't commit crimes, but are not doing well in their post. For people such as this, we should improve the selection system to ensure they are not appointed in the first place, or can be quickly removed from the post if they don't perform.

Some officials are hypocritical. They constantly talk about anti-corruption measures and always emphasize that their hands are clean, but that's just a cover. In reality, they are corrupt themselves.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Op Rana

Op Rana Berlin Fang

Berlin Fang Zhu Yuan

Zhu Yuan Huang Xiangyang

Huang Xiangyang Chen Weihua

Chen Weihua Liu Shinan

Liu Shinan