Waiting for their half of the sky

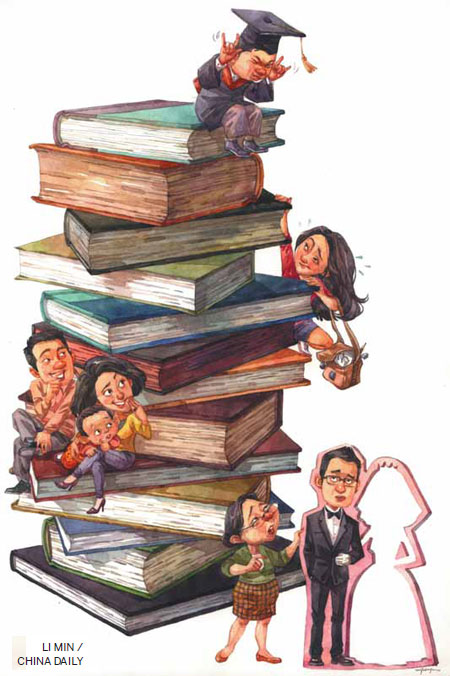

By Yang Yang ( China Daily ) Updated: 2014-02-14 09:34:47While progress has been made, gender stereotypes and a lack of specific laws continue to foster discrimination against women, Yang Yang finds out.

In 1968, Mao Zedong presented an inspiring vision of the role of women in society when he declared they "hold up half the sky".

His words have resonated across the decades, inspiring many Chinese women to aspire to greater heights of personal achievement, both at home and in the workplace.

But lingering sexist attitudes - leftovers from a patriarchal past - and outright gender discrimination in education continue to impede their progress.

Undeniably, significant improvements have been made for women, and in today's China people frequently mention gender equality in a variety of contexts including education and employment - not just when the unavoidable biological reality of childbirth comes up.

Yet, on the whole, women remain at a disadvantage and there is still a long way to go, according to advocates for women's rights.

For them, nothing demonstrated that fact more clearly than remarks by a male member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference in Guangdong province in January.

In a discussion with other members, Luo Biliang, a distinguished professor, compared women to a commercial product with a limited shelf life. Studying for a doctorate degree would devalue a woman, he said, if she has failed to sell herself to a husband in a timely fashion.

Women, especially educated ones, were incensed by the comment.

Adding fuel to the fire, another male CPPCC member, Chen Riyuan, also a professor, said that if a woman seeking to enter an advanced degree program had no husband or boyfriend, he would advise her to get one before taking the entrance examination.

Such insertions of marriage into virtually any discussion involving women is commonplace in China, where cultural expectations and assumptions run deep - so deep that many people don't even notice the built-in patronizing sexism that separates women from men.

Expressions may be well-meaning, whether from parents, friends, employers or teachers, but women's advocates say they are not appropriate in arenas that ought to be strictly gender-neutral, such as employment or education.

Tracy Zheng, 31, a doctoral candidate at Nanjing University, said three of her male professors frankly urged her to find a boyfriend before it was "too late".

"I understand it is kind-hearted for them to say that to me," Zheng said. "I was disappointed and despair at this so-called gender equality. "But I kind of start to believe that maybe they were right: Being happy might be the most important thing for a woman."

That doesn't sit well with Lyu Pin, a 42-year-old activist. For a woman, Lyu said, this sort of "being happy" means ingratiating herself with a society that persistently equates a woman's success with marriage as if that's all there is to life.

Op Rana

Op Rana Berlin Fang

Berlin Fang Zhu Yuan

Zhu Yuan Huang Xiangyang

Huang Xiangyang Chen Weihua

Chen Weihua Liu Shinan

Liu Shinan