Another one on the way

By Joseph Catanzaro and Yan Yiqi in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, and Li Aoxue in Beijing ( China Daily ) Updated: 2014-02-17 09:47:25Recent relaxation of the one-child policy has huge demographic implications for China and the world, report Joseph Catanzaro and Yan Yiqi in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, and Li Aoxue in Beijing.

In an otherwise unremarkable hospital waiting room in Zhoushan, the first city in China to move away from the one-child policy, an expectant father places his hand on the protruding curve of his wife's belly.

"This will be our second child," said Le Zhangfeng as he flashes a proud smile.

Those simple words, so frequently uttered elsewhere in the world, have a special gravity in China, where for almost 40 years more than 60 percent of the population has been subject to a one-child policy.

|

|

On the leading edge of demographic change, Le Zhangfeng and his wife, Zhou Na, are expecting their second child. Joseph Catanzaro / China Daily |

Le's wife Zhou Na's second baby is the harbinger of a new generation, newly allowed after family planning rules were relaxed in November.

"We just love children," he said Le, a tall and quiet 31-year-old real estate agent. "I think the more the merrier."

Whether most eligible Chinese couples share his sentiment and opt for a second child is an open question. The answer will have a profound impact not only on individual households but on the world.

In the halls of power in Beijing and in corporate boardrooms, the gentle bulge pressing against the front of 23-year-old Zhou's shirt represents more than just another new life. It is the tip of a demographic iceberg that can make or break more than just China's fortunes. For businesses and economies around the globe, Chinese babies and balance sheets have become inextricably linked.

The one-child policy, rolled out across the nation in the late 1970s in a bid to speed development and increase per capita income, is estimated to have prevented some 400 million births at a time when it was reasoned China could least afford them.

But in 2012, the world's most populous nation and second-largest economy saw an alarming decline of 3.45 million working-age Chinese, the result of a plummeting birthrate and a growing bulge of senior citizens. With that pattern expected to continue for the next 20 years, economists and demographers warn that relatively fewer workers will stunt economic growth as labor scarcity sparks wage hikes and inflation drives businesses to cheaper pastures.

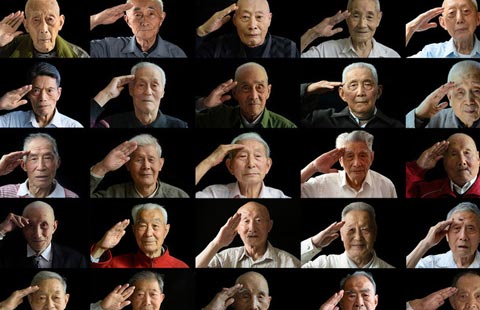

Currently, about 14 percent of the population has reached or passed the male retirement age of 60. Conservative projections suggest that by the early 2030s, some 400 million people - more than the projected total population of the US - will be 60 years or older.

Wang Peian, deputy director of the National Health and Family Planning Commission, said China's working-age population will shrink by an average of about 8 million annually from 2023 as the aging problem continues to worsen.

The latest census figures (2010) show an average of 1.54 births per Chinese woman, well below the estimated six children per woman in the early 1970s. It's also below the replacement rate of 2.1 births.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Op Rana

Op Rana Berlin Fang

Berlin Fang Zhu Yuan

Zhu Yuan Huang Xiangyang

Huang Xiangyang Chen Weihua

Chen Weihua Liu Shinan

Liu Shinan