Film shines new light on dark chapter of Canadian history

By NA LI in Toronto | China Daily | Updated: 2018-05-26 02:14

While Chinese immigrants' contributions have essentially been erased from the pages of history, Karen Cho, a Chinese-Canadian filmmaker, aimed to set things right by making the film In the Shadow of Gold Mountain.

This film took her from Montreal to Vancouver to uncover stories from the last survivors of the Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act, a dark chapter in Canadian history from 1885 until 1947 that plunged the Chinese community in Canada into decades of debt and family separation.

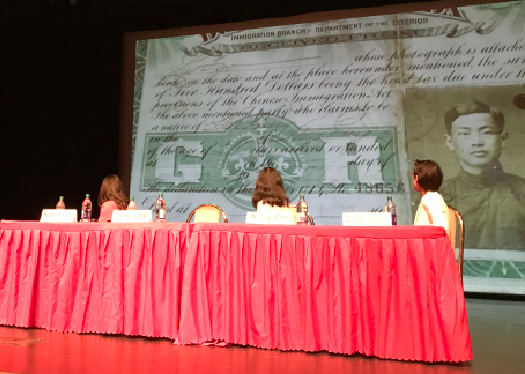

Last Monday marked the 71st anniversary of the repeal of the Exclusion Act of 1923. At a screening that was part of Asian Heritage Month in Toronto, Cho, 24, said that although the Head Tax and Exclusive Act were old stories, they were completely new to her.

"I couldn't understand why this dark period in our history was completely absent from the narrative of Canada that I had been taught, and for me this was the jumping-off point for making the film," said Cho, a fifth-generation Canadian of mixed Chinese and British heritage.

Cho was struck by how many people she had met while making the film. They had been separated from their families for a length of time that equalled her lifetime — the Chinese Exclusion Act lasted from 1923 to 1947.

Since Dominion Day — now known as Canada Day — coincided with the enforcement of the Chinese Immigration Act, Chinese-Canadians at the time referred to the anniversary of Confederation as "Humiliation Day" and refused to take any part in the celebration.

"While the British, Scottish and Irish ancestors were given free land to settle, citizenship, and their efforts were celebrated as nation building, the Chinese were charged a head tax, excluded from immigrating," Cho said.

She remembered attending a community debate in Winnipeg over whether or not to support the call for redress. A man stood up to express how ashamed he was that the community would dare ask for an apology. "If it weren't for my grandfather paying the head tax, I'd be rotting in a rice paddy field somewhere," he said.

She was puzzled by this sentiment. "This man's comment embodies the legacy of enduring decades of state-sanctioned racism: The inability to recognize that your community is worthy of the same privileges and citizenship rights of other Canadians."

The film shows the debate and the acceptance of being labelled "the other" despite the fact that generations of their family have lived here, and a failure to see that they are Canadian because they have been treated as a second-class citizens for so long.

However, far from a story of victimhood, the film tells of the heroes who built the Pacific Railway that made the Canada Confederation possible and fought for the Allies in World War II to win citizenship rights.

In the film, one of the descendants of head-tax payer Gim Wong, who was ultimately left out of the government's payout although he joined the Canadian Army in World War II, rode his motorbike across Canada from BC to Montreal to bring attention to the call for redress at the age of 82 in 2005.

"Gim was one of many inspiring examples of determination that helped turn the tide in the fight for reorganization, an apology and compensation for head-tax payers and their families," Cho said. "In his words he was a rabble rouser; in my words he is a Chinese-Canadian hero."

The Canadian Parliament repealed the act on May 14, 1947. However, independent Chinese immigration to Canada came only after the liberalization of Canadian immigration policy in 1967.

On June 22, 2006, former Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized in the House of Commons. He announced that the survivors or their spouses would be paid approximately C$20,000 in compensation for the head tax.

"The government only made an apology because we fought for it. It was not something that was given to us; this is something we earned," said Chinese-Canadian lawyer Avvy Yao-Yao Go.

She was executive director of the Chinese Canadian National Council (CCNC) in 1988 and president of the Toronto Chapter of the CCNC in 1989, when she became involved in the Redress Campaign for the Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act.

"The discrimination still exists. Sometime it's just subtle and systemic," said Yew Lee, former co-chair of the Ontario Redress Committee and Volunteer with CCNC, a descendant of a head-tax payer who was featured in the film.

"There are lots of smart and qualified Chinese Canadians with post graduate degrees, doctors, lawyers, yet we're not represented even at the deputy minister level in the federal government. … There is still work to be done," Lee said.

"The formal apology for the Exclusion Act made by the previous Conservative government is an important step towards reconciliation and recognition of the Chinese community's contributions in the shaping of our country," said Senator Victor Oh, who hosted the screening event at the Greater Toronto Chinese Cultural Centre.

"We should continue to learn from the past and fight against other social injustices, in the hope that mistakes will not be repeated," Oh added.

Contact the writer at renali@chinadailyusa.com