In with the old, in with the new

By Mei Jia | China Daily | Updated: 2018-09-01 08:30

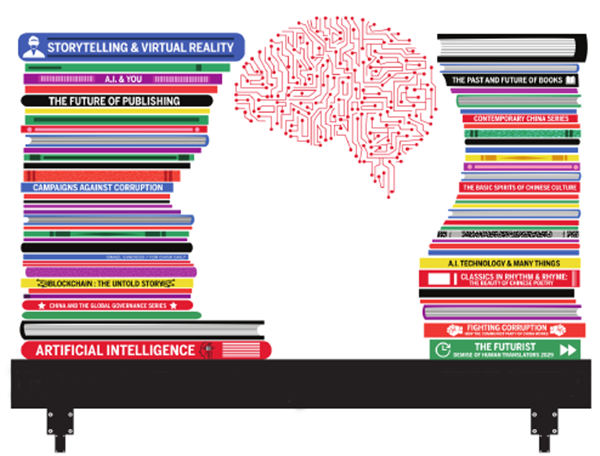

A powerful demonstration of the use of artificial intelligence in publishing was the talk of a recent book fair, but there was plenty of evidence that even as technology continues to carry the industry forward, China's past will continue to provide it with a strong foundation

Two first-of-its-kind books representing two prominent publishing trends rubbed shoulders when they were launched at the Beijing International Book Fair, the world's second-largest book fair, that ended on Aug 26.

At the fair visitors were able to wear virtual reality equipment that took them back to historic scenes such as the Red Army's Long March of 1934-36 and the Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan in 2008.

They could also relish the magnificence of the Grand Canal from Beijing to Hangzhou during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) by interacting with their smartphones connected to a big screen displaying images of the canal.

An encyclopedia robot got to show off its skills to enthralled visitors, and some stalls presented the beauty of thousand-year-old Chinese characters or paper binding techniques.

About 300,000 people visited the fair, organizers said, and over its five days more than 1,000 book events were staged throughout Beijing.

At the fair 1,520 publishing organizations from 92 countries and regions joined another 1,000 local publishers and cultural related organizations. What they witnessed was a publishing world pushing on with the task of integrating the very latest technology into everything it does, even as it proudly embraces China's past and holds firm to its cultural roots. In doing so it is well aware that it has a receptive audience not only at home but increasingly abroad.

In short, for Chinese publishers it is a matter of in with the old and in with the new.

On the first day of the fair, visitors were able to get a taste of what may be the world's first book written - well, translated - by artificial intelligence.

The book in question was a Chinese rendering of Blockchain: The Untold Story by Srinivas Mahankali translated by an identity going by the name of Youdao AI Translator. So efficient was the translator that the Publishing House of the Electronics Industry published the translation simultaneously with the original English version.

"In fact, at first we were a bit worried when we learned that we would be working with a machine translator," said Wang Chuanchen, president of Publishing House of the Electronics Industry.

"However, our confidence was restored when we saw the artificial intelligence's first draft."

It took the AI translator, powered by NetEase Youdao's Neutral Machine Translation technology, 30 seconds or so to render the English book of 100,000 words over 308 pages into Chinese. Liu Renlei, vice-president of Youdao, says the final print version combines AI's primary output with human editing.

The team spent an extra of two weeks to finish up, including editing, polishing and rewriting.

"AI keeps learning as it's being fed more linguistic data. In this case the book was quite easy because it's a science work written in plain language, devoid of human emotion. We know how much more work needs to be done before AI can become a perfect translator."

Publishers may well be licking their lips as they admire AI's productivity - they would normally expect a translation such as the one it performed in half a minute to take half a year - but translators, many of whom already feel overworked and underpaid, are likely to have had a less glowing take on what AI holds for their prospects.

In fact Ray Kurzwell, an American futurist, has been brave - or foolhardy - enough to put a date on the demise of human translators: 2029.