Movie magazines mirror China's history

By WILLIAM HENNELLY in New York | China Daily USA | Updated: 2018-09-29 05:07

Cleveland to China

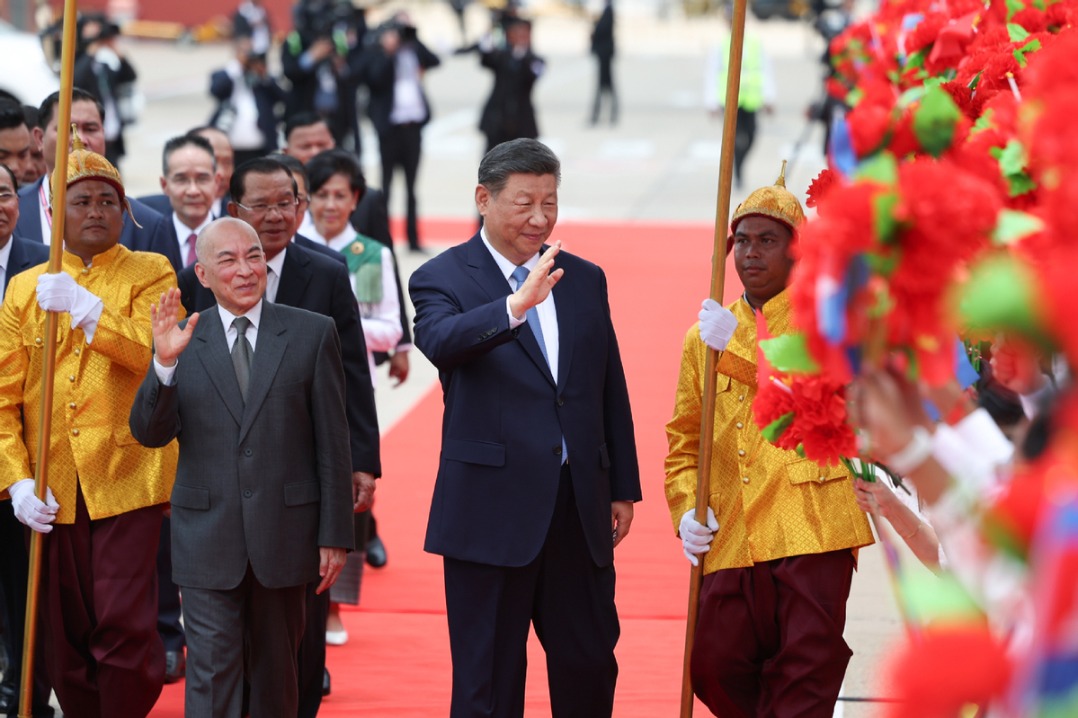

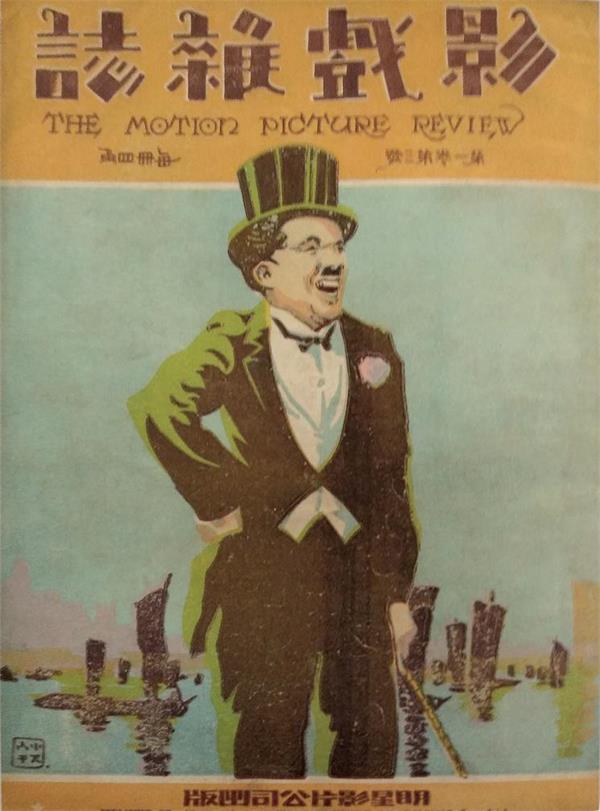

Charlie Chaplin, whose movie Pay Day would premiere in China the

week of the magazine’s issue.

Fonoroff was born in Cleveland, Ohio, and studied Chinese language at Brown University. He earned a master's degree in fine arts at the University of Southern California and a PhD at Peking University in Chinese cinema.

He initially intended to study Japanese.

"My father was a professor at Case Western Reserve, so I could take courses there for free (in high school). They had no Japanese class, but they had a Chinese class … so I started studying Chinese, and I really fell in love with the language."

After getting a degree in Chinese at Brown, Fonoroff went west.

"I was studying film at the University of Southern California, and it was just around the time when America and Beijing re-established diplomatic relations," he recalled.

"So my father sent me a little notice from one of those academic journals. They started offering fellowships for people to study in China. So my father said, 'Well, if you can't get a job in Hollywood, why don't you go to China?

"And he didn't realize that's exactly what I wanted to do. By that time, I had studied Chinese for like nine years. But you had to come up with a research topic, and so I wasn't particularly interested at all in Chinese film, but I studied film, and I was interested in Chinese, so hey, Chinese film, so that's how it started."

He wanted to attend the Beijing Film Academy, but it wasn't accepting foreigners then.

"This is back in 1980. So I went to Peking University … I gradually was able to work out my connections, so my second year I really saw lots of film … and I was finally able to go to the Beijing Film Academy."

China once had a movie industry that could rival Hollywood (Haolaiwu) in the 1920s and 1930s, but internal political upheaval and invasion were frequently intervening.

China's motion picture industry, initially centered in cosmopolitan Shanghai, featured its own stars and studios, such as Chan, Butterfly Wu and the tragic Ruan Lingyu.

Hong Kong, Macao, Beijing and Tianjin also were film centers.

"Once I started looking into Chinese movie culture, Shanghai movie culture, I realized it really wasn't that strange or foreign a topic because there was a lot of Hollywood influence in Shanghai movies," Fonoroff said.

"I really think that you cannot write about Chinese films before the 1949 era if you don't have a solid background in Hollywood movies of the '20s, '30s and '40s."

Key years in China's film industry depicted are 1911, when the Qing Dynasty was overthrown; 1931, when the swordswomen of wuxia (a martial arts genre), and shenguai (mystical) films were banned; 1932, when the Japanese attacked Shanghai and burned down the city's movie studios and theaters; 1937, when again the Japanese invaded, up until the formation of the People's Republic of China in 1949 under Mao Tse-tung.

War clouds

In 1937, the Japanese did not shut down the foreign-owned concession districts, which comprised "Orphan Island", and the film industry still managed to function in Shanghai.

"War is devastating to everything … less and less film … less and less electricity," Fonoroff said. "In a monetary way, it cut off the markets. … You don't have your audiences anymore, and if you don't have ticket sales, you're not going to have that many movies being produced."

Five years later, the Japanese consolidated all the Chinese studios under one umbrella.

"When the Japanese combined all of Shanghai's 12 studios into one big studio in 1942 (what they called Zhonglian) … for the first time you had everyone being able to work together. … You have combinations of directors and actors that you didn't have before. … That was interesting in a creative way.

"From late 1938 until around 1940, the big trend was historical drama, because that was the only way that you could in a roundabout way criticize or comment on the present situation," he said.

"You couldn't talk about the Japanese invasion but you could talk about, 'in the Ming Dynasty when the Mongol hordes were attacking China'. And everybody knew what they were talking about."

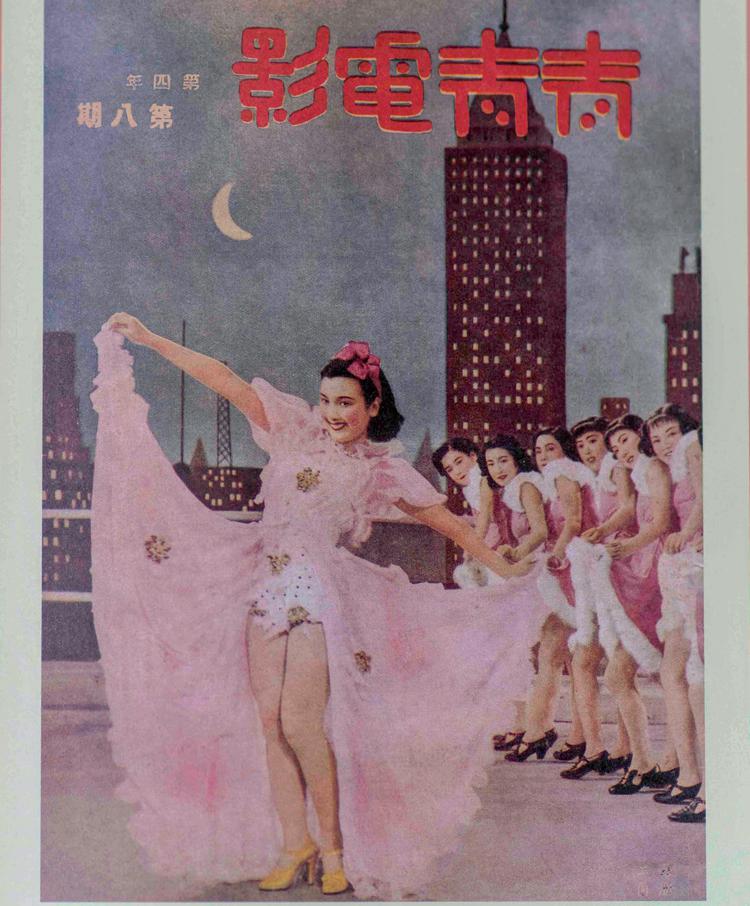

The magazine covers in the book include sophisticated Art Deco drawings, and are often in both Chinese and English.

"In Hollywood magazines … in the '20s and '30s, it's always the movie star on the cover. But in Chinese magazines, up until around 1935, you had a lot of just purely graphic art that wasn't connected to any star," Fonoroff explained.

"Some of them were leading artists of the time, at the beginning of their careers," referring to the graphic artists.

"They're really beautiful," he said of the covers. "Even though I've looked at them already a million times, I am still amazed by them."

Hollywood legends such as Clara Bow, Maurice Chevalier, Jeanette McDonald, Ingrid Bergman and Shirley Temple also appear in the book, reflecting the global influence of the American film industry.

The movie magazine covers of that day also were dominated by women. When male stars did make the covers, they usually appeared with women. A 1933 poll in China showed that 7 out of the 10 most popular screen stars were female.

The era also had its share of controversy.

American actor Harold Lloyd, who for a couple of decades had been enormously popular in China, appeared in the 1929 film Welcome Danger, set in San Francisco Chinatown. Its showing in Shanghai sparked a near riot.

"The portrayal of the Chinese (in the movie), they were all sinister and opium dealers; it just so outraged the audience that the film had to be shut down basically," Fonoroff said.

Fonoroff hopes the book works on two levels.

"One, if you could just leaf through it and look at the nice pictures … read it piecemeal, and the other is if you really look at it from beginning to end … my goal was that you get a feel for the entirety of Chinese cinema during that era as it relates to society and politics and everything, plus the fun things like the movie star gossip," he concluded.

Contact the writer at williamhennelly@chinadailyusa.com