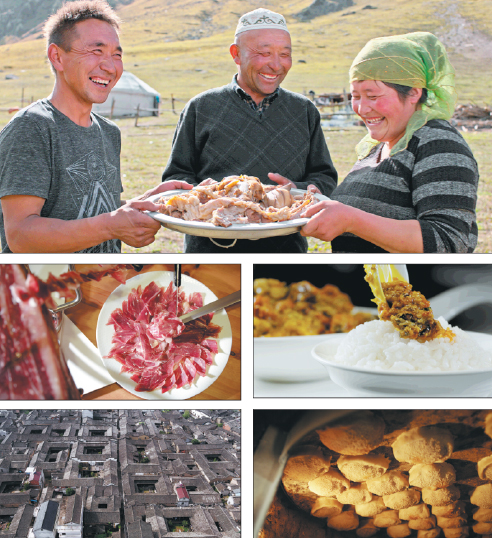

Food for thought

By Dong Fangyu | China Daily | Updated: 2018-11-16 08:05

"We see both the differences and the harmonies of distinct cuisines while documenting the unique features of Chinese food with a global perspective.

"For instance, it's not only Chinese people who enjoy eating pungent foods like Mandarin fish and stinky tofu. People around the world have their own smelly delicacies."

In one upcoming episode, the show draws up a map of foods around the world that are characterized by their strong odor.

Chen says the diversity of its food is vast in a country as immense as China. "It is not until the world gets to know how rich, different and diverse Chinese flavors are that they can begin to know genuine Chinese food."

In one episode, the documentary depicts different stages in which Chinese food is perceived in London, starting with dishes that are rarely offered within China but widely known in the West, such as General Tso's chicken, says Chen.

It then visits Chinatown and the restaurants serving Sichuan and Cantonese cuisine, through which the city gets closer to the real flavors in China.

Now, he says, there's a third stage where Chinese specialty and regional dishes are cropping up in London, such as spicy biang biang noodles from Shaanxi, pan-fried baozi (stuffed buns) from Shanghai and jianbing guozi (deep-fried dough sticks rolled in a thin pancake) from Tianjin.

Fuchsia Dunlop, an English writer specializing in Chinese cuisine and author of the bestselling book, Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper, appears on the show, explaining how Londoners get to know China through its food.

Another highlight of the show is the use of macro and microphotography. Through these filming techniques, viewers get to see the reactions among different ingredients and how subtle changes occur under certain conditions, arousing thoughts about how certain flavors and tastes are formed.

For instance, it shows how, when acidic ingredients are applied to crabmeat, the meat fibers instantly unfold, offering an explanation as to why crab tastes better with lemon or vinegar dipping sauce.

"For many foods, there's no secret recipe, no complicated preparation, no sophisticated cooking technique. They just taste best in the places from which they originate," Chen observes.

"Food is so bound to local culture and geography. That's why Chongqing's xiao mian (spicy noodles) taste best when you have the dish in Chongqing and why you will not find better chang wang mian (intestines and porkblood noodles) anywhere other than in Guiyang."

Chen and his team behind the camera did an enormous amount of research and spent a long time preparing before actually filming. They consulted experts, including Hong Kong gourmet writer Chua Lam, food critic Shen Hongfei and epicure Chen Li, who are the three chief consultants of the documentary series.

Beijing-based gourmet Dong Keping says that Once Upon A Bite has managed to capture the traditions that are evaporating in the urban rush of post-industrial society.

"Food and languages are the two distinct properties of a culture, and that is why the series has many scenes of people saying the names of the dishes in their own languages," Dong says.

Chen and his team also hope to evoke the memory of childhood flavors.

"Our taste preferences are largely developed during childhood. What you used to eat and enjoy then will carry over into later life. The flavors of our childhood are coded into our eating habits," he says.

Production of the next season of Once Upon A Bite is already underway, Chen notes. But he is unwilling to reveal the theme of the second season. He simply hints that it will demonstrate a wider ambition to explore food among different countries and cultures, along with the relationship between humans and the Earth.

"The food journey is like an adventure. I get to know more about the land upon which I live and the planet that belongs to us all," he concludes.

The show airs on Zhejiang TV and Tencent Video at 9 pm every Sunday.

Contact the writer at dongfangyu@chinadaily.com.cn