A 'chemical reaction' with China

Xinhua | Updated: 2019-01-02 07:47

He was also involved in developing new flame-retardant materials that can make electric cables safer and reduce the density of smoke in case of fire, giving people more time to escape.

He became president of the Royal Society of Chemistry's Beijing section in 2008. He received the China International Science and Technology Cooperation Award, the only national scientific and technological award for foreigners, in 2005. Prince Charles inducted him into the Order of the British Empire three years later.

British friends started to recognize his vision and asked him to help them contact Chinese researchers for cooperation.

China's scientific and technological progress also surged.

For example, the research team with which Evans now works has advanced equipment worth tens of millions of dollars in their lab, which was a basic facility two decades ago. The team has grown from a few people to over 100.

"In the past, people thought foreigners were here to help China," Evans says. "But now, scientific and technological cooperation between China and Britain is complementary and fully two-way."

China has many advantages that Britain lacks, he says. He's currently promoting a joint research project of China, Britain and Thailand.

Evans has taught himself Chinese, developed a taste for spicy cuisine and nurtured an interest in hutong (alleyway) culture.

Recently he began to engage China in a new way: science popularization.

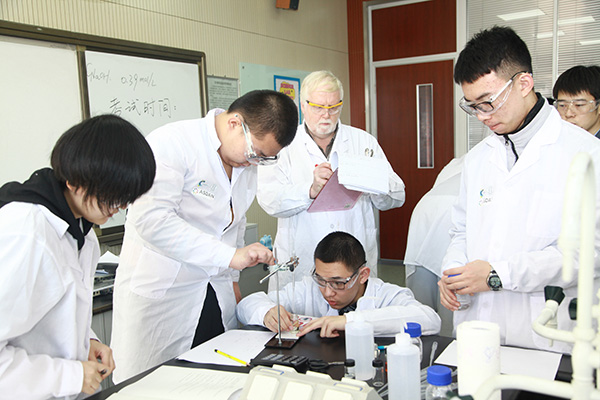

Students were amazed when he performed an experiment at a middle school. Chemistry classes involved memorizing the periodic table, theories and equations, and cramming for tests.

"However, the fun of chemistry is doing experiments," Evans says.

The Royal Society of Chemistry gave every local section 1,000 pounds ($1,200) to promote chemistry in imaginative ways to mark the International Year of Chemistry in 2011.

Evans used the grant to set up the Fun with Science program, offering practical chemistry classes in primary schools for migrant children in Beijing's suburbs. He presented the classes with his students. The kids' excitement reminded him of his own when he was a boy.

Evans has since turned to the internet to popularize science.

He learned short-video apps are also popular in small cities and rural areas. And he realized this enables him to reach more students, who lack opportunities to perform fun experiments. But even a one-minute video requires a tremendous amount of work. Still, it's worth it to fulfill his responsibility to popularize science, he says.

His experiments always fill schools' lecture halls with laughter.

He uses jokes and metaphors-for instance, he compares catalysts to China's Good Samaritan Lei Feng, a flask spewing smoke to Aladdin's lamp and mounds of bubbles to "elephant toothpaste".

Many public figures and commercial organizations have started popularizing science via social media in recent years, but he believes scientists have the advantage of years of hands-on research.

Some viewers call him "a Harry Potter-like magician", but he disagrees. "A magician never tells the secrets behind his tricks, but a scientist always gives an explanation."

He sees himself as a teacher. He performs experiments to spread knowledge, inspire thinking, remove misunderstandings and show that science can create change.

He has no plans to retire soon. His university recently built a science classroom for him in a building full of key laboratories.

He has also been invited to join a science-popularization association initiated by senior researchers across the country.

Evans says he looks forward to more "chemical reactions" with China.