College scam: top schools not always best

By Liu Yinmeng in Los Angeles | China Daily Global | Updated: 2019-03-18 23:05

The college admissions scam that rocked the nation last week laid bare the extreme measures, sometimes illegal, that wealthy parents are willing to undertake to secure their children a spot at elite universities.

While sometimes a degree from a prestigious institution might be a pathway to financial stability and social status, some experts and educational consultants argue that the scam reveals a flawed perception by parents that entrance to elite universities is their children's only route to success.

"I think that because of the ranking publications, because of all the press that those top institutions received, it has really created an unfortunate situation that some families believe that that's the only way their child can be successful and can be happy," said Stefanie Niles, president of the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

"In actuality, there are many pathways to a high-quality educational experience," Niles said.

The $25 million scheme, exposed by federal agents last Tuesday, revealed how wealthy parents bought their children entrance into schools like Stanford or Yale through bribes, cheating on standardized tests or faking athletic credentials.

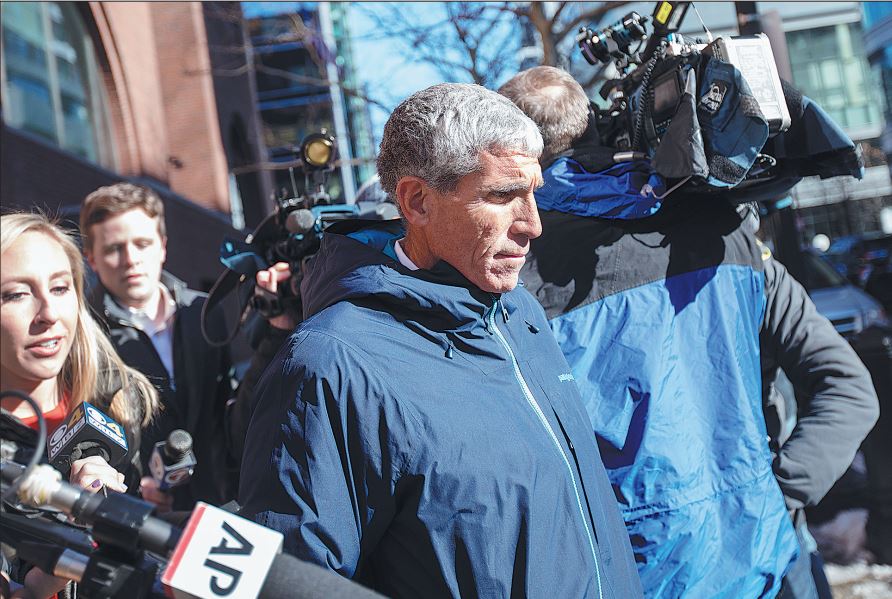

The scam, orchestrated by 58-year-old William Singer, implicated a batch of people described by the prosecutor, US Attorney for Massachusetts Andrew Lelling, as "a catalogue of wealth and privilege", which included famous Hollywood celebrities and prominent CEOs.

Arun Ponnusamy, chief academic officer at Collegewise, an educational consultant company, said that to some of these parents, sending their kids to prominent schools is a symbol of prestige and reputation.

"I understand that parents love their children, but, this particular scenario it seems like they may have loved themselves a little bit more," Ponnusamy said. "Where your kids go to college is almost the proof of how good a parent you've become."

According to authorities, parents paid Singer anywhere between $100,000 to $6.5 million to have their children admitted to a tiny group of highly select institutions.

These well-to-do parents' obsession over elite schools underscores a common perception in society that enrollment in a top university leads to a good career and a good life.

This phenomenon means many families are willing to do everything in their power to give their kids an edge in the admission process.

Alexis Redding, a visiting scholar at Harvard's graduate school of education who has studied college admissions for more than a decade, said the pursuit of elite college admission has taken on a "win at all costs" mentality for some families.

"This scandal highlights some of the worst instincts of society — greed, entitlement, and hubris," she said.

"The focus should not be on prestige and brand names. Parents should be focused on helping their teens explore the full range of schools to find a college that is a fit and where they will thrive both academically and socially," Redding added.

But getting into elite schools is not unique to the wealthy, it is a desire shared by families across all social classes and ethnic backgrounds.

Steven Mercer operates an independent educational consulting practice based in Santa Monica, California. His client list ranges from domestic patrons to families from overseas, including China.

Mercer said there's a tendency for Chinese families to focus on schools with high rankings, and part of the reason for that is their unfamiliarity with the subjectivity of America's ranking systems.

"Our rankings are very different; they are primarily rankings that come from publications, like U.S. News and World Report, or Forbes, or Washington Monthly, which are all, again, businesses that are trying to sell newspapers, or magazines or subscriptions, and rankings, well, they try to be honest about it, their motivation is different, and there are varying rankings," he said.

China's 985 and 211 projects, as well as the "double-first-class university plan", were developed by the Chinese government to strengthen universities. They also provide a standardized and comprehensive list of top universities in China.

In a 2015 report, the Brookings Institution stated that "popular rankings from U.S. News, Forbes, and Money focus only on a small fraction of four-year colleges and tend to reward highly select institutions over those that may contribute the most to students' success."

By depending on ranking systems such as U.S. News, Chinese families, who have already spent a significant amount of money to send their children to study abroad, are just trying to find the simplest way to identify the best schools, Mercer said.

"I think the intentions of the families are good," he said. "I don't question people's intention or their purpose. I just think it gets twisted sometimes around obsessing over only highly select schools."

Ponnusamy said Chinese families' focus on top American universities also has to do with competition in the job market back home.

"The people who do hiring at many companies get so many applications that their sorting mechanism is simply to look at who went to an elite American university; they don't consider the schools that they haven't heard of," he said.

Ponnusamy said, however, that many Chinese families are starting to recognize the value of less prestigious universities.

"It's getting better, but this takes time, and education, and people would have to have open their ears to listen to educators who know what they are doing," he said.

In a study published in 1999, researchers Stacy Berg Dale and Alan B. Krueger found that "students who attended more selective colleges do not earn more than other students who were accepted and rejected by comparable schools but attended less selective colleges".