Aussie scientists set up contest to foil cocky robots

Xinhua | Updated: 2019-11-02 10:15

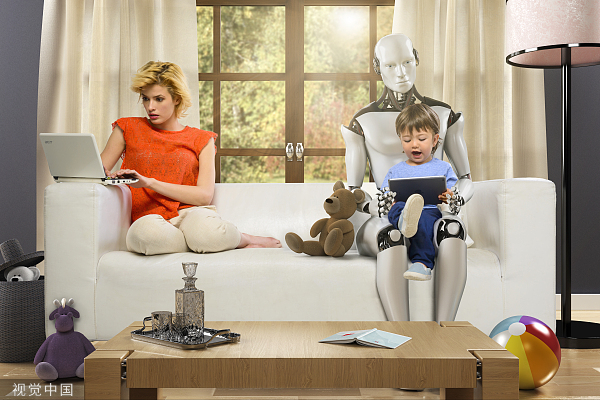

We could soon live in a world where domestic service robots perform household chores and clean up for us as we go about our daily lives. But what if your new mechanical helper decides to put your laptop in the dishwasher, places your cat in the bathtub and throws your treasured possessions into the trash?

Current vision systems being tested on "simulated" domestic robots in the cluttered, unpredictable environments of the real world, are suffering severely from what experts refer to as overconfidence - meaning robots are unable to know when they don't know exactly what an object is.

When introduced into our day-to-day lives, this overconfidence poses a huge risk to people's safety and belongings, and represents a barrier for the development of autonomous robotics.

"These (models) are often trained on a specific data set, so you show it a lot of examples of different objects. But in the real world, you often encounter situations that are not part of that training data set," Niko Sunderhauf explained to Xinhua. He works as a chief investigator with the Australian Center for Robotic Vision, headquartered at Queensland University of Technology.

"So, if you train these systems to detect 100 different objects, and then it sees one that it has not seen before, it will just overconfidently think it is one of the object types it knows, and then do something with that, and that can be damaging to the object or very unsafe."

Earlier this year, in an effort to curb these potentially cocky machines, Sunderhauf's team at the ACRV launched a world-first competition, the Robotic Vision Challenge, inviting teams from around the world to find a way to make robots less sure of themselves, and safer for the rest of us.

Sunderhauf hopes that by crowdsourcing the problem and tapping into researchers' natural competitiveness, they can overcome this monumental stumbling block of modern robotics.

The open-ended challenge has already captured global attention due to its implications regarding one of the most excitement inducing and ear-tingling concepts in robotics today - deep learning.

While it dates back to the 1980s, deep learning "boomed" in 2012 and was hailed as a revolution in artificial intelligence, enabling robots to solve all kinds of complex problems without assistance, and behaving more like humans in the way they see, listen and think.

When applied to tasks like photo-captioning, online ad targeting, or even medical diagnosis, deep learning has proved incredibly efficient, and many organizations reliably employ these methods, with the cost of mistakes being relatively low.

However, when you introduce these intelligence systems into a physical machine which will interact with people and animals in the real world - the stakes are decidedly higher.

"As soon as you put these systems on robots that work in the real world the consequences can be severe, so it's really important to get this part right and have this inbuilt uncertainty and caution in the system," Sunderhauf said.

To solve these issues would undoubtedly play a part in taking robotics to the next level, not just in delivering us our autonomous housekeepers, but in a range of other applications from autonomous cars and drones to smart sidewalks and robotic shop attendants.

Since it was launched in the middle of the year, the competition has had 111 submissions from 18 teams all around the world and Sunderhauf said that while results have been promising, there is still a long way to go to where they want to be.

The competition provides participants with 200,000 realistic images of living spaces from 40 simulated indoor video sequences, including kitchens, bedrooms, bathrooms and even outdoor living areas, complete with clutter, and rich with uncertain objects.

Entrants are required to develop the best possible system of probabilistic object detection, which can accurately estimate spatial and semantic uncertainty.

Sunderhauf hopes that the ongoing nature of the challenge will motivate teams to come up with a solution which may well propel robotics research and application on a global scale.

"I think everybody's a little bit competitive and if you can compare how good your algorithm and your research is with a lot of other people around the world who are working on the same problem, it's just very inspiring," Sunderhauf said.

"It's like the Olympic Games - when everybody competes under the same rules, and you can see who is doing the best."

In November, Sunderhauf will travel with members of his team to the annual International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems in Macao, China to present and discuss their findings so far.

As one of three leading robotics conferences in the world, IROS is a valuable opportunity for researchers to come together to compare notes, and collaborate on taking technology to the next level.

"There will be a lot of interaction and discussion around the ways forward and that will be really exciting to see what everybody thinks and really excited to see different directions," Sunderhauf said.