Brexit election remains too wide open to predict

By Harvey Morris | China Daily Global | Updated: 2019-11-15 06:55

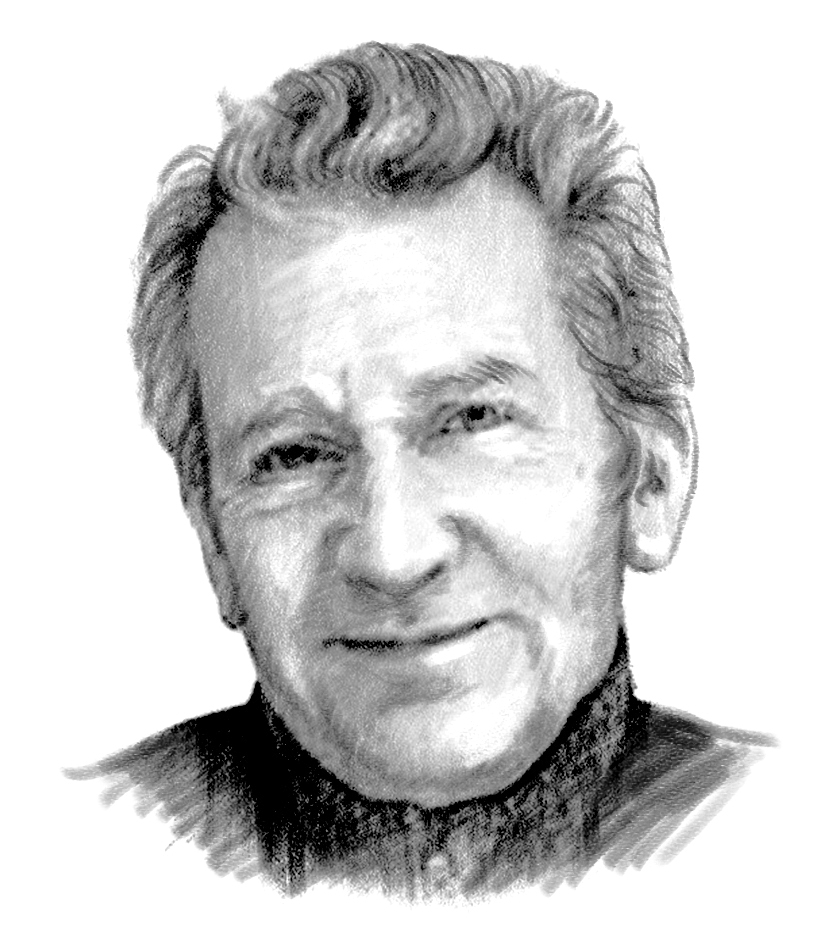

Harvey Morris is a senior media consultant for China Daily UK

The United Kingdom has just embarked on its most significant election campaign in several generations and no one has a clue what kind of government will emerge.

It would take a very brave and foolhardy spirit confidently to predict the outcome, in the words of one political commentator reflecting the general mood ahead of the Dec 12 vote.

The uncertainty that the country faces as it contemplates its second general election in little more thantwo years can be summed up in one word: Brexit.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson decided not to push his latest version of a deal on the UK's departure from the European Union through a divided Parliament and instead chose to gamble on an election.

For decades, UK politics was dominated by a two-way split between the Conservative and Labour parties, with the first appealing historically to a property-owning salaried middle class and the latter basing its support on wage-earning workers and their trade unions.

That class-based dichotomy was already crumbling in the last century when Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher targeted her pitch at the aspirational working class, and later Labour's Tony Blair built a mandate among middle class progressives.

Simmering beneath this relatively benign evolutionary process was the issue of the UK's membership of the EU. It was a question that divided firstly the Labour Party and subsequently the Conservatives, although it figured low down the electorate's list of priorities right up to the 2016 referendum.

The narrow 52-48 percentage victory for the Brexiters that year divided the entire electorate, over an issue to which many had not previously given a second thought.

Since then it has been the single issue dominating the political landscape and there is no guarantee December's election outcome will resolve it.

The result could give Johnson the extra parliamentary seats he needs to push through his Brexit deal; it could hand Labour, or conceivably the resurgent pro-European Liberal Democrat Party enough votes to become the largest party; or it could produce the same kind of divided Parliament that has been paralyzed by Brexit since 2017.

With the Lib Dems promising to abandon Brexit and Labour and others pledging a second referendum-style vote, there is still no clarity on whether the country will leave the EU or not.

The UK's neighbors and partners can only look on with increasing disbelief - indeed growing irritation, in the case of the EU - as the Brexit drama approaches its fourth anniversary next June.

While the economy has been hit by the continuing uncertainty, some foreign investors have put their plans on hold or shifted their UK activities elsewhere until it is resolved.

One bright spot on the economic horizon was the emergence of Chinese steelmaker Jingye Group as a potential buyer of bankrupt British Steel, a move that would save thousands of jobs in recession-hit regions.

Despite the centrality of Brexit to the current election campaign, the main parties appear determined to talk about anything but it. Both Conservative and Labour have made broad pledges of massive public spending, while dismissing the other's as fairy tales.

In what could be described as the UK's first post-truth election, visions of a golden future are being touted by both sides with little detail about how it will be achieved.

Such partisan propaganda may be having an impact on some voters, even when shown to be false.

This month, the pro-Conservative Daily Telegraph was forced to correct a column written by Johnson which falsely claimed the UK was set to "become the largest and most prosperous economy in this hemisphere".

The vitriol of the current campaign threatens to compound the toxic political atmosphere that prevailed in the outgoing Parliament. A number of moderate MPs, and a disproportionate number of women, decided to quit politics rather than endure growing levels of abuse.

As the election approaches, opinion polls offer little guidance. Johnson's Conservatives are in the lead with more than one-third of anticipated votes, enough to ensure an overall majority in more normal times.

But with pro-Remain voters being urged to vote tactically and uncertainty over the electoral stance of the right-wing Brexit Party, the UK's first-past-the-post electoral system means any outcome is possible.

Reformers have long called for a change in the system to allow elections to award parliamentary seats according to the proportion of votes that go to parties nationwide. That option was rejected in a referendum in 2011.

Amid indecisive polling, some analysts have turned to the odds offered by bookmakers in a country where political betting is big business. Most indicate there will be no clear majority or a 50-50 chance of a narrow Conservative win.

However, the same bookmakers predicted a comfortable win for Remain in 2016 and a victory for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump the same year. So the British have to worry as much this year about how to place their bets as about how to cast their votes.