Lives of iron forged in tribulation

By ZHAO XU in New York | China Daily | Updated: 2020-02-25 03:13

From a railroad construction site in the Sierra Nevada to the sun-kissed citrus gardens of Florida, Chinese who made the perilous voyage across the Pacific Ocean to start a new life helped build a nation.

One morning in fall 2016, Michael Perrone, president of the Belleville Historical Society in Belleville, New Jersey, was inspecting a church cemetery he had been helping restore for the past 20 years.

"Suddenly, I saw a tip sticking out of the ground, by an inch and a half," he said. "It looked like the bow of a ship. We dug it up and it was an iron, the same type of iron that laundry workers would have used."

Last October, Perrone was at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) in New York telling his story to attendees at the opening of the exhibition Gathering – Collecting & Documenting Chinese American History.

"For 20 years we cleaned that cemetery and probed every square foot with probes and metal detectors," an emotional Perrone said. "For 20 years we never found a thing. Then came this iron, announcing its existence to us on the very morning after we dedicated a monument to early Chinese immigrants who first came in 1870, brought by a retired sea captain, James Hervey, to work at what was then the country's largest commercial laundry."

That was little more than one year after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad linking the American east and west, on whose construction 23,000 Chinese immigrant laborers were employed, and more than 20 years after the discovery of gold in California brought the first wave of Chinese immigrants to the US.

However, in the collection of works featured in this exhibition, the museum president, Nancy Yao Maasbach, sees a history that goes back even further, one that "has been created not in the past 100 years, not in the past 150 years, but in the past 200 years".

One organization present to tell this early story is the Hawaii Chinese Cultural Center founded in 1970. According to the wall text, Chinese, often prompted by civil unrest and famine, began migrating to the Hawaiian islands nearly 230 years ago, first as traders, then as sojourners to begin small sugar plantations.

Later they were brought to the United States to teach those in the budding sugar industry how to cultivate the plant and mill it into sugar, and they eventually served as a source of labor themselves.

The story is one of the many being told by the exhibition, which draws on the strength of 28 cultural institutions across the US (there is also one from Canada), all dedicated to ensuring that the history of Chinese America expands and endures.

With each organization contributing an exhibit, the iron being an example, the exhibition seeks to offer revealing and often evocative glimpses into a history whose depiction is at its best "generic and fuzzy", as Herb Tam, the exhibition curator, puts it.

In a distortion of history, the California Gold Rush – in which about 300,000 people arrived on the West Coast in the two and a half years or so before California became the 31st state of the union in 1850 – is still attributed by many as the beginning of that story.

On view at the exhibition is a set of fortune sticks found in a temple built around 1854 by Chinese settlers who arrived around that time in Mendocino, 150 miles (250 kilometers) north of San Francisco, by sampan, a small, flat-bottomed wooden boat with a shelter.

The oral history that has been passed down for four generations is that seven sampans sailed to California, those on board hoping to find gold, but only two survived the 6,000-mile (10,000-kilometer) journey. As planned, one landed at Monterey, 90 miles (150 kilometers) south of San Francisco, as planned, and the other at Caspar Beach, 4 miles (7 kilometers) north of Mendocino.

Intertwined in almost every story of the early Chinese immigrants are episodes of fortune and misfortune, of hope and sorrow – those who desperately wanted a fresh start in a distant land, constantly feeling the pull of the loved ones they left behind.

For the new arrivals, the temples provided not only physical shelter but a mental and emotional respite as well. In later days, schools, sometimes housed in the unlikeliest of places, were opened to teach children Cantonese. (For more than 120 years the great majority of Chinese immigrants would come from Guangdong province, also known as Canton.) The need for language education was often outweighed by the need for communal bonds, especially during the subsequent era of exclusion and racism.

Antagonism toward the Chinese started to arise near the end of the Gold Rush in the mid 1850s, when gold became scarcer and competition fiercer. By that time, San Francisco, which grew from a small settlement with a population of just a few hundred in 1846 to a boomtown of about 36,000 by 1852, had witnessed the birth of the first Chinatown in the US.

In 1863, the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad began, with two concerns, the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific Railroad companies, racing toward each other from Sacramento, California, at one end, to Omaha, Nebraska, at the other, struggling against great risk before they met at Promontory, Utah, completing the line of 1,900 miles (3,077 kilometers) on May 10, 1869.

Working for the Central Pacific, the 23,000 Chinese laborers – some arrived earlier, and others were recruited by the company from Guangdong – had to battle the toughest terrain and severest weather, with 44 storms recorded in 1866 alone.

Writing for the New York Daily News last May, Larry Lee, whose great-granduncle was among the laborers, said: "Before tracks could be placed, laborers built 15 tunnels through the solid shale and granite walls of the Sierra Nevada Mountain range, which rose to 7,000 feet (2,100 meters). Hung by ropes or suspended by baskets, Chinese workers chipped away at rock with hand-held picks. They planted dynamite charges and scrambled up the ropes before the explosions."

That scene is now on view at MOCA, in the form of a postcard painted by the Chinese American artist Jake Lee in 1963, nearly 100 years after the Chinese immigrant laborers performed their engineering miracle.

It was one of a dozen watercolors depicting Chinese in America between 1860s and 1900. The series was commissioned by the Chinese American restaurateur Johnny Kan, credited with popularizing authentic Chinese cuisine as a fine dining option, with Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin being regular patrons.

The effort by later generations of Chinese Americans to acknowledge the contribution of their forefathers was often met with resistance, said Eugene Moy, an amateur historian who sits on the boards of several participating organizations for the Gathering exhibition, including the Save Our Chinatown Committee in Riverside, California.

"Today, few are willing to recognize the fact that the city of Riverside would not exist if it had not been for the wealth generated through Chinese labor," he said, referring to the role of early Chinese immigrants in turning California into one of America's biggest agricultural states, a feat some historians have called the second Gold Rush.

"Chinese labor is no longer involved now, having been replaced by Mexican or Latino farm worker population," Moy said. "But back then the majority of those who plowed the American fields were Asian – Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean. … Coming from the food-growing areas in southern China's Pearl River Delta, the Chinese immigrants took their rich knowledge in crop cultivation to California and elsewhere in the US."

One of them was Lue Gim Gong (1860-1925), otherwise known as "The Citrus Wizard". Arriving in the US with his uncle aged 12, Lue cross-pollinated citrus while working in orange groves in Florida, giving birth to a popular variety still sold today.

A horseshoe at the MOCA exhibition offers a more vivid example. Five times bigger than average, the horseshoe has an additional ring attachable to the standard shoe that would be worn by the animal. It was developed by the immigrant Chinese farmers to let the animal stand afloat and maneuver better on the area's marshy peat soil, soil whose potential they first recognized.

A few steps away from the iron shoe is a horse collar that once belonged to Belle, the horse of Joshua Fong, while plowing at the Fong family farm in Fremont, 40 miles (70 kilometers) from San Francisco. The Fong family first came to the US in 1917.

Before his death, Fong, an optometrist who later founded the Bay Bank of Commerce, penned his own memoir, in which he wrote: "She (Belle) knew that the 12 o'clock whistle from a tile plant a half-mile away meant lunch time or quitting time, so she hurried back at the sound … and she was not even a union member!"

There were certainly happy memories for the Chinese immigrants, but they were heavily scarred by the antagonism and outright hate they had to endure, especially between the mid-1850s and World War II.

"Sadly, the life of many early Chinese settlers followed a similar pattern," Moy said. "They set foot on a piece of land, usually along the route of the Transcontinental Railroad, cultivated it and built a Chinatown on top of it, before they were being forced out and moved a few miles away, where they started up a second Chinatown, with no better guarantee for safety. Sometimes they stayed in place because they had nowhere else to go."

Both the Riverside site and the Sacramento River Delta site, where the large horseshoe was found, were testimony to such stories. Having endured the vicious mosquito bites and having built numerous drainage canals and levees to reclaim the land for farming, the Chinese settlers saw a fire destroy one of their towns in 1915. They moved a couple of kilometers north up the river, built a new town and named it Locke, the name of the landlord that serendipitously rhymes with a Chinese phrase meaning happy living.

For Gerry Low-Sabado, a fifth-generation Chinese fishing village descendant, that fire story is all too familiar. On May 16, 1906, most of the village in Pacific Grove, on Monterey Bay, was "mysteriously" burned down, he said. The Chinese tried to rebuild, but townspeople tore down what they built, and the military was called in to build a fence to keep them out.

"Eventually my great grandfather, who was considered part of the 'resistance', was the last man to leave the village site in 1907. After that, zip – no one talks about it," said Low-Sabado, whose ancestors crossed the Pacific in a junk with no engine and whose great grandmother was the first documented Chinese female born in the Monterey area.

A more discreet and deceptive tool of defense was a sword cane once carried around by a man named Ah Quin, known as the "unofficial mayor of Chinatown" in San Diego. The cane, on display in the museum and befitting a revered community leader, is capable of a lethal thrust once unsheathed.

However, discretion seemed to be a scarce trait: In the 1870s and 1880s, about 500 anti-Chinese riots broke out in the US. "Apart from California, there were very violent incidents in the mining communities or agricultural towns in Oregon, Idaho, Washington state, Wyoming, Nevada … where there was big competition for labor," Moy said. "But at the same time, a lot of antagonism towards the Chinese was based on race instead of economic competition."

One salient example, Moy said, was the enforcement in San Francisco of the Pole Ordinance. People who carried laundry around in baskets that hung from a pole –which in effect meant Chinese laundry workers – were taxed, while those who used a cart or a horse were not.

Many similarly grotesque measures of discrimination were enacted throughout the US, culminating in the passing in 1882 of the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned all Chinese from entering the country unless they were businessmen, scholars and diplomats.

The act, the first immigration law that excluded an entire ethnic group, created numerous bachelor societies throughout America, whose members saw all hope of bringing their wives and children dashed.

Some tried to help. The Lung Kong Tin Yee Association was established in the 1920s by a group of Chinese merchants able to arrive after 1882, to serve partly as a boardinghouse for the bachelors who arrived in Memphis, Tennessee, between 1865 and 1877.

Due to the combined factors of a job shortage and racism on the West Coast, many Chinese immigrants embarked on a journey that took them to many other parts of the country.

Most died alone, leaving behind nothing but a bunch of unsent letters, and with no idea of the last charitable act performed for them by their compatriots on both sides of the ocean.

The single most evocative item in the exhibition is a bone-repatriation book from 1894, owned today by the China Alley Preservation Society in Hanford, California. The written record, the only such copy found in the history of American Chinese, includes detailed descriptions of the deceased: what Chinese village they called home, how they came to Hanford and at what age.

Usually, the remains were exhumed several years after the initial burial, for the bones to be collected and sent home, to their ancestral villages on the southern Chinese coast. Often the journey was paid for by regional associations or charitable organizations in China, Tung Wah Hospital in Hong Kong being prominent among them.

Such trips home were interrupted in the 1930s and '40s, first by World War II and then by civil strife in China. From 1930, more than 1,500 Chinese immigrants, mostly solitary sojourner-workers, were laid to rest at Mount Hope Cemetery in Boston, Massachusetts. In 2007, members and supporters of the Chinese Historical Society of New England erected a memorial in their honor.

Massachusetts, colonized by the British in the early 17th century, proved to be hostile when the first batch of Chinese arrived by train in the early 1870s, brought in to replace union workers who were on strike at a shoe factory in North Adams, 220 kilometers east of Boston.

The Chinese, unaware of their role as strike-breakers, were met by 2,000 angry people at the train station, before 50 policemen armed with shotguns escorted them to the factory.

The Chinese, realizing they had been duped, left for other places, including New York and New Jersey.

About the same time, 68 Chinese boys and men, aged 3 to 32, arrived in Belleville, New Jersey, recruited by a ship captain, James Hervey, for the laundry business he owned. Hervey had "a deeper understanding of the Chinese through his previous trading with China", said Perrone of the Belleville Chinese Historical Society.

"As home to the first Chinese community on the East Coast, Belleville embraced the newcomers while the rest of the country rejected them."

In January 1871, a few months after the Chinese arrived, they held their first Lunar New Year celebration in Belleville. "New York city didn't allow public Chinese New Year celebrations until 20 years later," Perrone said.

Later that year, the Belleville Chinese Sabbath School opened. A joint venture of Belleville's three churches, including the Belleville Reformed Church in whose cemetery the iron was discovered, the school taught English and Bible study and by its first year enrolled 60 pupils.

Perrone attributes acceptance of the Chinese in Belleville to the town's liberal history. "During the American Civil War, Belleville was staunchly anti-slavery while New York and the rest of New Jersey, although nominally staying within the Union, were sympathetic toward the South."

Then there was the influence of one man, the Reverend Thomas De Witt Talmage, a vociferous advocate of the Chinese. Talmage, hoping like his brother to become a missionary to China, successfully lobbied president Rutherford B. Hayes to veto the original Chinese Exclusion Act passed by Congress in 1879, only to have president Chester A. Arthur sign it into law three years later.

Tam, the exhibition curator, says Perrone, whose childhood connection with China included going to Chinatown in Belleville to buy fireworks and reading about the adventures of Marco Polo, was far from the only ethnically non-Chinese person interested in the history of Chinese Americans.

"One of the places I went to in preparation for the exhibition was the Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site, a tiny museum of 1,000 square feet (93 square meters), located in a mountainous area in John Day, eastern Oregon," Tam said. "When you go inside, there's an audio guide telling you what it was like in the 1880s. The feeling is visceral."

It is the only stone building in Chinatown in John Day and was once used by Kam Wah Chung & Co, a Chinese general store-cum-herbal medicine shop. John Day was a mining town in the mid-1880s and had the third-largest Chinatown in the US, after San Francisco and Seattle, Washington, or Portland, Oregon, depending on the year.

Tam said: "The Chinese had left a long time ago, but there's a group of people, almost all white, who got to know the former owner of this place – a Chinese doctor famous for his herbal remedies – through their parents and grandparents and decided to honor his memory. They came together and raised money. Now the site has been listed as a National Historic Landmark, with an annual visitor number that roughly equals that for the Museum of Chinese in America."

Another institution that stands out on the basis of location is the Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum, which Tam describes as "a hub that connects a lot of Chinese Americans in that region".

Emily Jones, archivist and curator of Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi, inside which the museum is housed, presented at the exhibition opening a wooden sculpture of Jesus made by a self-taught artist who was a butcher for his entire life.

"The Chinese first settled in Mississippi in around 1870 following our civil war," Jones said. "Caught between the very opposed societies of white and black, they were able to negotiate with the Caucasians and the African Americans. And the way they did that was through church and faith."

Bearing in mind the enormous effort undertaken to take those bones back to China to fulfill an unuttered wish, it seems that Chinese Americans were always pulled in different directions by the competing forces of isolation and assimilation.

But whichever force may prevail at a certain point for a certain individual, there has always been a sense of pride, both in their cultural heritage and their collective contribution to the making of America.

The watercolor postcards commissioned by Kan and on display in his popular restaurant in San Francisco are an example. According to Moy, if Save Our Chinatown, the movement to record the history of Chinese Americans "probably began in the early 1960s".

"The involvement in World War II by Chinese Americans was really a major turning point in the way the Chinese were treated, accompanied by a greater awareness that these were people who were part of American society," Moy said.

In 1943, a year after China and the US became allies in World War II, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed, although only symbolically, when the quota of Chinese allowed into the country was raised from zero to 105. It would take another 22 years for that number to make a substantial jump, to 10,000.

In the 1960s and 1970s, more and more Chinese Americans not only went to college and got an education, but also landed jobs thanks to less and less discrimination in the workplace. This rising middle class, aware of its own roots, sought to learn more about that history and to preserve it.

In 1963, the Chinese Historical Society of America was founded in San Francisco, the first of its kind dedicated to researching the history of Chinese in America. Six years later, Brian Tom, a law student at the University of California at Davis, joined with other students and demanded that the university start an Asian American Studies Program.

Tom's grandfather Hom Kun Foo came to the US in 1851, adopting the name Tom to replace his own similar-sounding family name Hom, a decision that may have represented a not-so-successful effort to blend in and stay out of harm's way.

From the University of California to Columbia University and Brown University, rising awareness led to increased scholarship, which in turn further fed curiosity and enthusiasm, and a long-buried history was gradually brought into the light of day.

And to accomplish that, those concerned had some physical excavation to do, many Chinatowns having been demolished and buried by then.

"Within 20 years in the 1930s and 1940s, one half of the old Chinatown in Los Angeles was cleared to make way for the now famous Union Station, with the other half losing itself to the construction of a highway," Moy said.

Among the historic structures demolished was part of the Garnier Building, outside whose steps on Oct 24, 1871, 17 Chinese men, including a 15-year-old, were killed by a mob.

"When the Chinatown was razed, fill dirt was added to level the tracks, 14 feet (4 meters) below which the remains of the once-thriving community was sealed," said Susan Dickson, president of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California.

"Then in 1987, when workers building the Los Angeles Metro Rail were digging under Union Station, they found all these Chinese artifacts – 200,000 pieces in total. They were given to us by the Metropolitan Transit Authority."

As Dickson spoke, she pointed to a reassembled famille rose porcelain vase that has survived to tell the story of its owner.

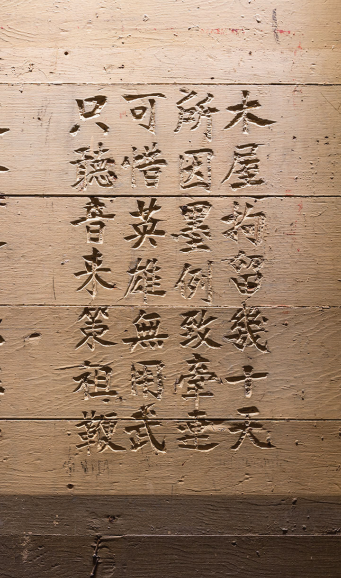

"History lost and rediscovered" could also be said of the poems carved into the barrack walls on the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco by its Chinese occupants.

From 1910 to 1940, many Chinese, with other Pacific Coast immigrants from more than 80 countries, were detained in the overcrowded barracks on the island, waiting for months and sometimes years as their applications to enter the country, based on being a child or spouse of a US citizen, were examined.

The Chinese poems were found in 1970, when the site was due to be demolished because of its poor condition.

The line of one poem penned by one of those confined in the immigration station reads: "Nights are long and the pillow cold; who can pity my loneliness?"

Today the station is a state monument.

Tam, reflecting on his own experience growing up in Chinatown in San Francisco in the 70s and 80s, and who was brought to the US by his parents in 1974, when he was 2 months old, said he was often angry.

"I was walking to school and a car was passing by. The white teenage boys sitting inside the car would roll down the window and hurl abusive words at us or make fun of my own language. Sometimes I shouted back but most of the time I just took it and kept going".

That was before he became increasingly interested in art and issues of self-identity. In 2011, after graduating from the School of Visual Arts in New York, Tam joined MOCA, founded in 1980 by Charles Lai and John Kuo Wei Tchen, who came to the rescue as precious memories of Chinese Americans in New York were being tossed away each time an old hand laundry closed or an elderly Chinese man or woman died.

"Working for the museum makes me realize that being a Chinese American is not this one thing," Tam said. "My experience is inextricably linked with how other people have gone through their life and how they have felt, but it's not everything."

At the exhibition's opening, the museum president, Yao Maasbach, said: "Why, after 200 years of being a part of the fundamental fabric of this country, don't Chinese Americans still see their stories being told in textbooks or around the world? It's not our fault, but we need to do the job. And we want to do it in a way that helps to educate people.

"There is not one moment that we cannot spend telling this story, because not only are we fraught with tension in the bilateral relationship – we are fraught with tension of Asian Americans and our roles in this country."

Perrone, born four months after his farmer parents arrived in New York from Italy, said all immigrants have been discriminated against to some extent, but it is Chinese who have suffered most because "they look different".

Looking back to that discovery of his on that autumn morning in 2016, Perrone said: "In the early days, the Chinese laundry workers were nicknamed the Iron Men."