Steeped in history

By Wang Kaihao | China Daily | Updated: 2020-07-21 07:44

The earliest artifacts related to tea in China reveal reciprocal influence between the drink and the civilization, Wang Kaihao reports. The earliest artifacts related to tea in China reveal reciprocal influence between the drink and the civilization, Wang Kaihao reports.

History was rewritten in many respects when the 1,200-year-old underground palace was unearthed at the Famen Buddhist Temple in Fufeng county, Shaanxi province, in 1987.

Though the bone remains, of which some are thought to be of Buddha, are generally considered to rank among the top archaeological discoveries in China in the 20th century, other items found in the 30-square-meter altar of a former Tang Dynasty (618-907) royal Buddhist temple are also unmatched.

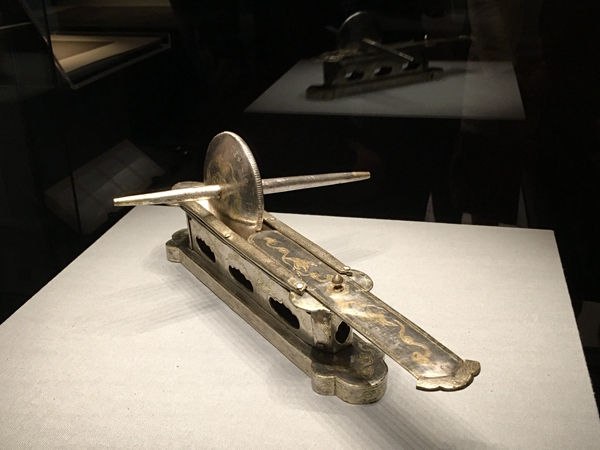

The exquisite silver tea set gilt with gold-including cages, a container with sieves, a grinder, spoons and other instruments-was the beloved possession of emperor Li Xuan, who reigned from 873 to 888 and donated to the temple to show his reverence for Buddha.

The world's earliest known tea set is now on show at an exhibition that opened in May at Shaanxi History Museum in the provincial capital, Xi'an, known as Chang'an during the Tang Dynasty, when it was the national capital and one of the world's biggest metropolises.

Liang Guilin, a researcher with the museum and a veteran scholar specializing in tea-related history, says the earliest known tea was pounded and shaped into cakes after being steamed and dried. These were stored in cages when taken to the royal palace.

"When people prepared to enjoy tea, they'd break the cakes into small pieces and grind them into powder," Liang explains.

Sieved tea powders were poured into boiling water. People added salt.

Boiling times were methodically controlled to produce Goldilocks conditions-not "too fresh" nor "too old", he says.

The set includes a tortoise-shaped container that's believed to be an incense burner used to enhance the experience.

"This tea set's discovery proves that tea ceremonies are rooted in China and offers a physical specimen of what's recorded in The Classic of Tea".

The Classic of Tea was compiled by writer Lu Yu and was first published in 780. It's the world's first known monograph on tea.

It offers comprehensive information about how different varieties were grown, processed, rated, cooked and tasted, as well as how tea sets should be designed and produced.

"It marks how the upper class then began to value tea's ceremonial significance," Liang says.

China has about 3,000 years of tea-drinking history, which began in today's Yunnan and Guizhou provinces and gradually spread northeastward.

That's separate from the legendary account that says tribal leader Shennong used tea as herbal medicine nearly 5,000 years ago.

When the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC) was founded, people in today's Sichuan province offered tea as tributes to the king.

The earliest specimen of tea in China was found in the mausoleum of Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) emperor Liu Qi.

Before The Classic of Tea, ordinary Chinese "ate" rather than "drank" tea.

"People made tea into soup," Liang explains. "In addition to salt, they'd mix in ginger, peppers, mint, orange peels and different spices."

Even after drinking tea became a ritual among aristocrats, monks and literati in the Tang Dynasty, it remained a way for commoners to feed themselves, Liang says.

That probably explains why salty tea and butter tea are common dishes in some regions of today's South China.

In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the ceremony evolved so that people poured boiling water into a bowl of tea powder.

This practice was introduced to Japan and remains how matcha is consumed today.

"Tea competitions" to designate top-level tea makers became popular throughout China.

Emperor Huizong (1082-1135), a weak ruler but an excellent artist, was a diehard fan of such competitions.

He wrote Treatise on Tea and thus left precious historical documentation of the tea industry during the period.

In the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the way of drinking tea became more casual by pouring water on loose leaves. This practice continues in the country today.

"During the Ming era, tea was pan-fried and dehydrated during processing, and then rolled and dried," Liang says.

"Oxidation was avoided. Green tea's original flavor was preserved. This technique was a big leap in the history of tea making and is still the primary method in China."

Liang's study of tea's development in China has led him to believe the leaves are more than a base for a beverage.

"Tea bears witness to how different cultures mix in China and is like an ambassador spreading Chinese civilization around the world," he says.

"It also represents Chinese people's philosophy and aesthetics, emphasizing harmony and elegance."

He considers an exquisite tea set to be the "father of good tea" and scalding water to be the "mother". The best tea can only be made through balancing different elements.

"As Lu Yu has pointed out, tea drinking is not simply to quench your thirst," Liang says.

"It needs a quiet atmosphere and simple lifestyle to fully appreciate the flavor. Ancient literati came to understand philosophy and even the wisdom to govern nations from cups of tea. Tea can continue to inspire us to look for inner peace and respect nature when pursuing our goals."