Will the Beijing subway 'rose' by any other name smell just as sweet?

By Li Yijuan | chinadaily.com.cn | Updated: 2022-01-20 17:33

First-time foreign visitors to Beijing might choose the subway as the easiest way to get around the Chinese capital, but in recent days they might find themselves at a loss when looking at signs ending in zhan instead of station.

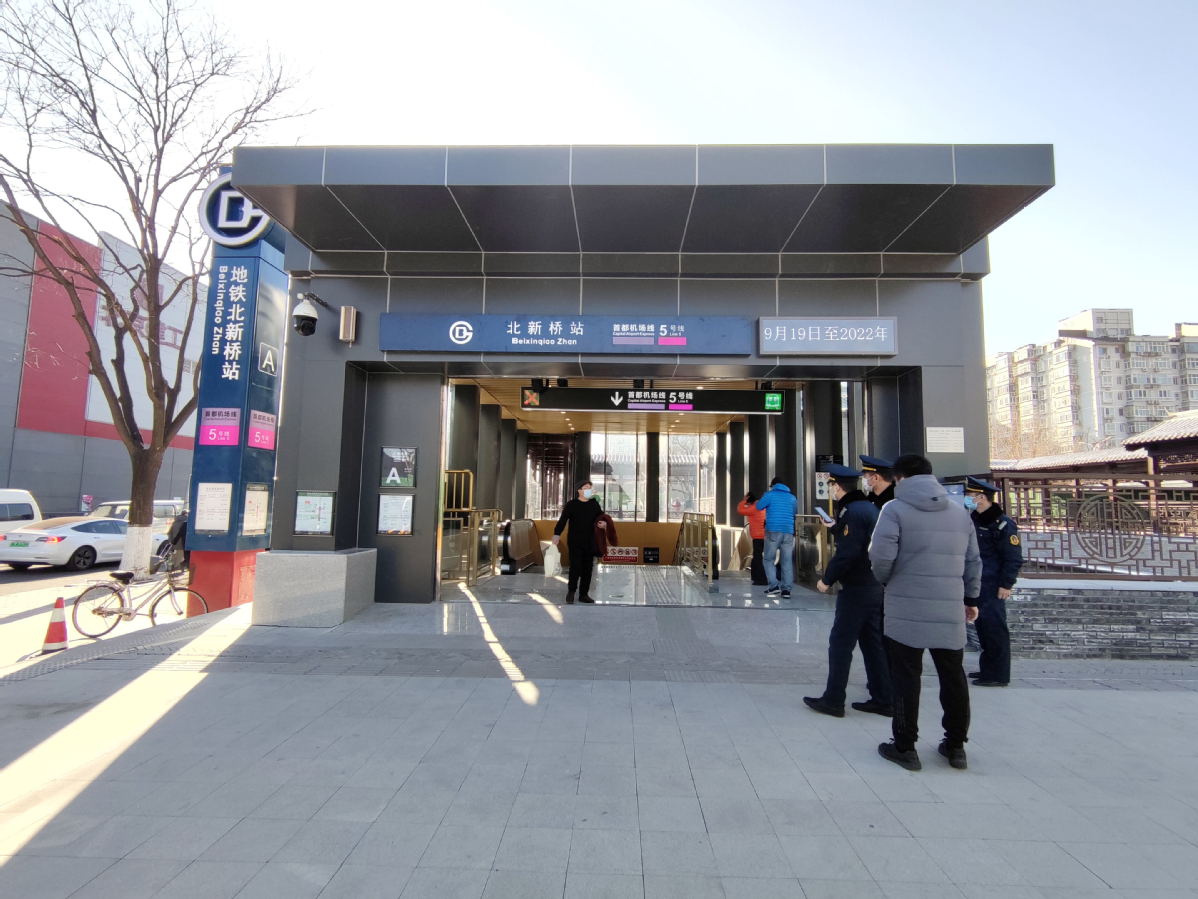

Last month, Beijing Subway started to use pinyin names to replace part of the English translations for subway signs. Notably, zhan substituted station and daxue replaced university.

The alterations caused a stir online. Many argued on the microblogging site Weibo that this would only confuse foreigners, with China Daily and Guangming Daily also calling for simple, clear translation.

By contrast, some commentators believed this move could prompt non-Chinese speakers to learn about the country. However, views were polarized, with some people overreacting with words like "ashamed of Beijing" or "no more English (in signs)."

While the debate in China mainly centered on the practicality of the name change, the foreigners I approached were also split.

Rohit, a Nepalese who studied in western China's Chengdu for four years and has returned home, knows what zhan stands for, but prefers station. "People with no or scant knowledge of Chinese could get very confused," Rohit said.

Meanwhile, Mathijs, a Dutch citizen living in Shanghai for four years, believes it won't be very confusing for most.

In any case, people still wonder about the rationale behind the shift. In response to queries from bewildered residents, Beijing Subway replied that the move is part of the efforts to unify translations of subway stations based on current regulations.

In 2021, Beijing set forth a unified translation standard of subway signs, requiring that pinyin spelling be used in lieu of English names. This came after previous reports highlighting the inconsistency in translation. For instance, Beijing Daily pointed out that some subway translations are incongruous with those of nearby places and railway stations.

Translation standards have changed multiple times. As early as 2006, regulations were passed that required names of public venues other than, say, museums be spelt in pinyin and appear in capital letters. In subsequent years, authorities made several modifications that largely hardened the stance on pinyin usages.

Indeed, unification matters for the convenience of foreigners and the city's image. But is it justifiable?

Actually, it might be. Take zhan as an example. Counterintuitively, it could improve practicality.

CNN interviewed Alistair Baker-Brian, a British national who lives in Beijing and speaks Chinese, weeks ago. He used the example of asking for directions to illustrate that locals are more likely to understand zhan than station.

Some foreigners I discussed the topic with also agree that the new signs may compel foreigners to pick up some survival Chinese. Robbie, an American who moved to Shanghai four months ago, said this would be confusing at first but soon enough foreigners will figure out zhan means station.

Similar stories abound of the character lu, which stands for street. Robbie said it was initially baffling to hear lu in daily chats with friends, but it took him only two days to figure out its meaning. Asked about his opinion of Beijing's new pinyin rules, he said "in the long run it will do some good."

Still, the revamped subway signboards remain unfathomable for people well-versed in translation. Some have lambasted the move as "having much ado about nothing."

"[Zhan and others] are neither translation nor pinyin. Useless for Chinese. Harmful for foreigners!" Jin Xueqin, a professor of translation studies at Sichuan University, complained.

"What matters for language, especially functional language, is convention. [The change] seems to be an unprofessional decision," said He Yujia, a veteran freelance translator.

Perhaps the reason Beijing's new subway translations sparked such a furor is that they concern the somewhat tricky issue of cultural confidence.

Although a change from station to zhan might only have a limited effect in boosting Chinese national confidence, it triggered a backlash in some Western media outlets.

In the same CNN report mentioned earlier, the broadcaster interpreted the move as a result of growing "anti-English" sentiments. But judging from the overwhelming online opposition to the pinyin translation, it is clear that many Chinese value cultural diversity.

The switch to pinyin, as many pointed out, could actually bolster cultural exchanges. Social media posts compared Beijing's seemingly "nativistic" move to the French word Renaissance and the Japanese word Ramen, which made their way into the English dictionary. They hope zhan will become another of such loan words.

In fact, the conundrum facing translation of public places' names is not exclusively Chinese, though some countries don't seem to go so far as to transliterate station.

For instance, the subway station near Japan's Nagoya University is named "Nagoya Daigaku Sta.," where station is translated and university is Romanized.

South Korean subway signs appear to have partially done away with the word "station." For example, Gyeongbokgung Palace, a tourist attraction in Seoul, has an adjoining subway station simply spelled as Gyeongbokgung.

As the pilot unification project in Beijing continues, it might be worthwhile to see how far it can go and whether it will spread to other parts of the nation.

If the episode has anything to teach us, it is that one should avoid meeting a seemingly nonsensical gesture with knee-jerk criticism and sarcasm.

At least, given the name change's practicality and its contribution, however subtle, to the national confidence, why don't we give it a cautious try?

The author is a postgraduate student studying at Fudan University.