Babusha's desert 'soldiers' hold back sands

By Hou Liqiang | China Daily | Updated: 2023-05-03 06:57

Babusha, which means "eight-step sands" in English, gets its name because according to residents, the desert was always just eight steps away from their doors.

As the local saying goes, all it takes is one night of wind from the north for the sand to rise as high as the wall, so that when you wake up in the morning, donkeys have climbed up onto your roof.

For generations, this area on the southern edge of the Tengger Desert, the fourth largest desert in China, was plagued by sandstorms that frequently buried farmland, often leaving nothing to reap.

Today, the desert's southward creep has been halted thanks to a green belt 10 kilometers in length and eight kilometers in width, planted over the course of the last 40 years by Guo Wangang and his colleagues.

As a result, Guo was named a National Moral Model in 2020.

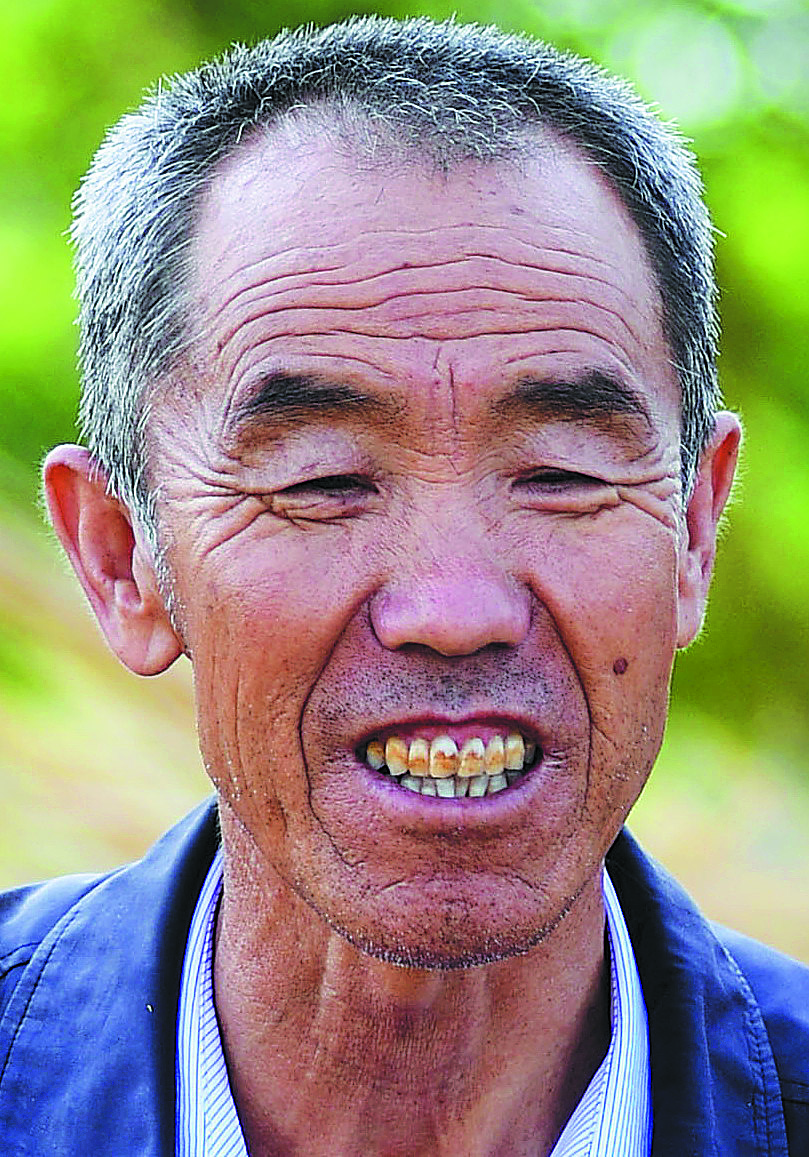

As head of the Babusha Forest Farm, the 71-year-old is part of the second generation of "soldiers" to fight against the desert in Gulang county, Gansu province. His father was one of the six men who first began planting trees in Babusha to prevent their land from being buried in 1981.

When he was forced to stop in 1983 due to poor health, Guo's father hoped that his son would follow in his footsteps but at the time, Guo Wangang was working at a local supply and marketing cooperative.

These government-run businesses can be found in many parts of rural China and Guo remembers being unwilling to give up his job, which was viewed as an "iron rice bowl", in other words, a stable government job that guaranteed a living.

Worse still, workers on the forest farm at the time endured arduous conditions. They lived in tattered tents put up over pits dug into the sand.

As they had no machinery, they worked with simple tools, and after a sandstorm, many of the saplings planted would be lost to the sand. At first, few survived, though they later discovered that putting straw around the saplings helped prevent them from being completely buried.

"My father repeatedly stressed that no matter how laborious the work, or how tiring it was, we had to make sure our farms weren't eaten by the desert," Guo said, adding that he eventually agreed to work at the farm because, as the oldest son, he didn't want to see the trees his father had so laboriously planted, die.

However, he didn't plan to spend the rest of his life fighting the desert. "Back then, it was terribly hard for a local farmer to make a living, so I didn't believe I'd be able to keep working on desertification control forever," he said.

However, a deadly sandstorm in 1993 firmed his resolve, turning Guo into a stubborn 'soldier', unwilling to give up the fight.

The fast moving brown wall of dust that reached up into the sky as it raged across Gansu and the neighboring Ningxia Hui and Inner Mongolia autonomous regions that May, turned day into night.

Guo was working in the desert with his colleagues when it hit. They only just managed to get home after trekking for six hours in darkness. Later, he learned that 23 students from his home county were found dead in a river as they tried to get home from school during the sandstorm.

"I asked myself then that if we couldn't protect our farmland or our children, how were we supposed to keep going?" Guo recalled. "That's when I made up my mind to devote my life to this fight."

Year after year, Guo and his colleagues have continued to plant trees each spring and fall, pruning them in the winter and watching out for fire.

Thanks to their efforts, the vegetation coverage rate in Babusha has increased from less than 3 percent to 70 percent and as a result of the green belt they've planted, the desert is no longer able to move further south.

Five of those six volunteers who began to push back against the desert in Babusha in 1981 have passed away, but their struggle continues. Guo Xi, who is the grandson of one, joined in 2017 and college students have also been recruited in recent years. Currently, the farm employs 20 people and has begun to outsource afforestation work, with some 300 local residents contracted to do projects each year.

Young employees have also turned to the internet to help promote their efforts.

The farm now replants almost 2,000 hectares of desert every year, some two thirds of which is subsidized by Ant Forest, a public welfare project launched by Ant Group, an affiliate of Chinese e-commerce giant, Alibaba.

Ant Forest is an app that rewards users with virtual energy in exchange for engaging in low-carbon activities like walking or using public transport instead of driving. The accumulated virtual energy can be used to do things, like having trees planted.

"We need more young people to help us find other scientific and engineering methods for desertification control," said Guo Wangang.

Xinhua contributed to the story.

houliqiang@chinadaily.com.cn