Reading numbers like poetry: A journey into ancient Chinese math

By LIN QI | China Daily | Updated: 2026-01-16 07:01

From mathematics to Chinese calligraphy and classical texts, and then back to math, German Sinologist Andrea Breard has forged a new path to reveal the logical and poetic beauty of Chinese mathematics, and the depth of Chinese culture.

Standing at the crossroads of the East and the West, and the past and the present, her focus is on ancient Chinese mathematics. Her research reveals that these texts from centuries or even millennia ago possess both formulaic logic and a quality of literary expression, and some are written in a rhythmic style to aid memorization.

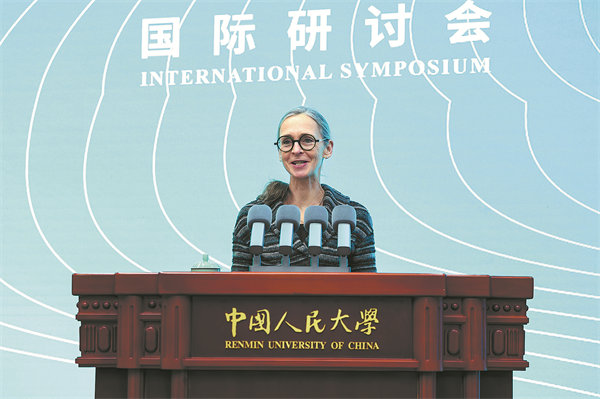

"If you look at an old Chinese math book … (you will find) it functions like a language. You can analyze the words, sense their logic and see how philosophical ideas and systematic, algorithmic thinking are expressed through mathematics," says the professor and vice-president of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universitat Erlangen-Nurnberg (FAU) in Erlangen, Germany, while attending the International Symposium on Young Sinologists and Mutual Learning Among Civilizations in Beijing from Jan 8-10.

The event, jointly organized by the Center for Language Education and Cooperation and Renmin University of China, gathered senior and younger-generation scholars who shared views on their vision of Sinology.

Breard's interest in Chinese scientific history was ignited by Chinese Mathematics: A Concise History, a book that chronicles China's mathematical developments over 2,000 years. Then a student of math and computer science at the Technical University of Munich, she was also an enthusiastic calligrapher and learner of Chinese.

The book helped determine her academic focus, and she later lived and worked in different cities worldwide, including Shanghai where she received her master's degree in the history of science from Fudan University in the early 1990s.

"Behind the mathematics, there were people," Breard says, explaining why she was drawn to the interface of math and Sinology. She says studying ancient mathematical texts offers insight and understanding of history and society, and "how knowledge was transmitted, and how mathematics was related to the social world and economic exchange".

She says that while there are differences in how the Western and ancient Chinese worlds presented theories and methods of proof, the two worlds also shared commonalities in mathematical research, for example, the Pythagorean theorem, or the Gougu Rule, which were proved by both sides.

Breard says people can also learn a lot about ancient literary forms like poetry, because some algebraic methods were written as poems, the rhythm allowing for better memorization.

"There are many connections, and they help you gain additional perspectives in Sinology," she says.

Understanding them, however, places greater demands on modern scholars, who must draw on knowledge of philosophy, history and linguistics across disciplines, a depth of expertise unlikely to be replicated by artificial intelligence in the near future.

She says her fascination with China motivated her to read and research these ancient texts, which provide her with another way of studying Chinese history and culture. "If I just give the work to AI and have it translate the text, that's not interesting for me. I'm not interested in reading an English version of an old Chinese text. I'd rather read it myself and try to understand it myself the way it is, in Chinese.

"Seeing the language structure, that's where the beauty is," she says.

Yang Huilin, a retired professor of literature at Renmin University of China, echoes Breard's view, saying that to understand contemporary China, one needs to appreciate the sentiments of the ancients. "Sinology serves not only as a channel for intellectual dialogue but also as a means of nurturing the mind and spirit," he says.