Is China losing competitiveness or moving up value chain?

By Wang Tao and Harrison Hu (chinadaily.com.cn) Updated: 2014-03-28 18:18II. The appreciation of the RMB

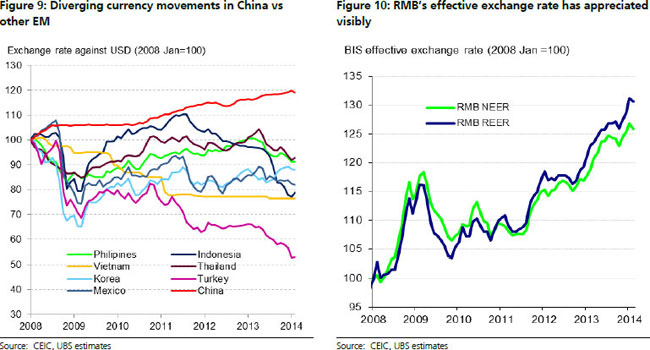

Indeed, the RMB has appreciated by almost 20 percent against the US dollar since 2008 while many other emerging currencies have either depreciated or strengthened only modestly against the green back (Figure 9). As a result, RMB's effective exchange rate, or the rate against a trade-weighted basket of partner currencies, has appreciated by 27 percent in nominal terms and 33 percent in real terms (adjusted by consumer price inflation) since 2008 (Figure 10).

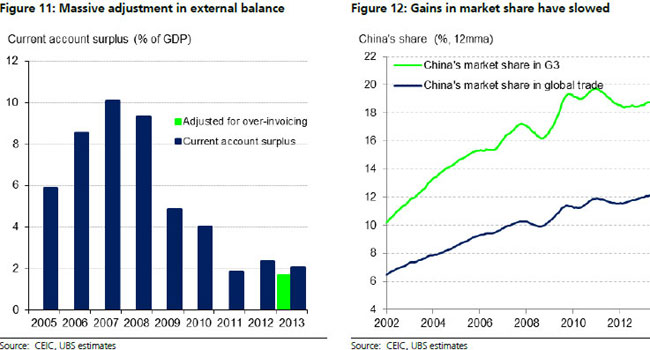

As a result of the substantial real appreciation, the RMB is no longer undervalued. Back in 2010, we used a number of methods and models to estimate the undervaluation of the RMB. Based on the most commonly used macroeconomic balance approach, our latest estimate shows that the RMB is no longer undervalued. China's current account surplus has fallen to just below 3 percent if adjust for the cyclical weakness in global demand, or what the macroeconomic fundamentals suggest as China's "equilibrium" current account surplus. In other words, the RMB is no longer undervalued from the macroeconomic fundamental's point of view. Even the estimate by the Peterson Institute, which has often been used by the US congress to support its pressure on RMB appreciation, suggests that RMB's undervaluation was largely gone by 2012.

III. Has China lost competitiveness?

The sharp real appreciation has led to an erosion of China's competitiveness. The simplest thing to look at is the adjustment in China's external balance – China's current account surplus has shrunk from the peak of 10 percent of GDP in 2007, just before the global financial crisis, to 2.1 percent in 2013 (1.7 percent if adjusted for over-invoicing of exports, Figure 11). As Chinese exports continue to outpace global trade, China's market share globally has continued to rise, albeit more slowly than before. However, China's market share in G3 economies has started to decline (Figure 12).

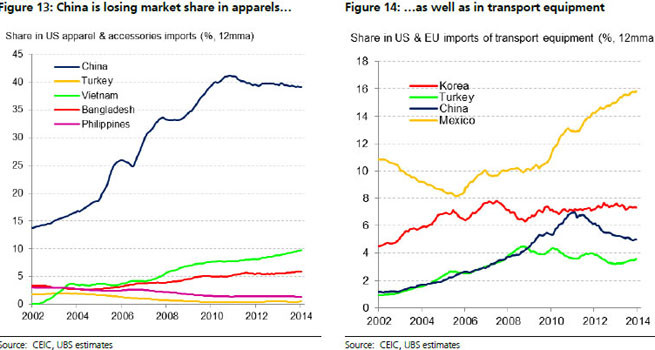

By sector, the loss of competitiveness in China's traditionally strong labour-intensive sectors has been more notable, including apparels, shoes and toys. For example, China's market share in apparels exports to the US has declined in recent years while cheaper products from countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh have gained ground (Figure 13). Another area that China seems to have lost out is transport equipment (automobiles and parts) – as shown in figure 14, China's market share in the US and EU have declined especially since the global financial crisis, while that of Mexico has risen substantially in the past decade. There may be additional reasons why such a change has taken place apart from the divergence in movements in labour costs. One possible reason is that transport cost matters with high energy cost, and Mexico's proximity to the US market and US auto producers is a great advantage. Another reason is that China's own domestic automobile market has grown rapidly into the largest market in the world, absorbing Chinese production and making exports less attractive.

- RMB internationalization could transform global markets

- Yuan enters new era with freer float

- Yuan fluctuation was not engineered, economist says

- China remains important global economic driver

- CICC expects China GDP to grow 7.3%

- ADB has confidence in Chinese economy

- China on new growth track within 2 years

- NHTSA says finds no 'defect trend' in Tesla Model S sedans

- WTO rare earth ruling is unfair

- Amway says 2014 China sales may grow 8%

- President Xi in Europe: Forging deals, boosting business

- CNOOC releases 2013 sustainability report

- Local production by Chery Jaguar Land Rover this year

- Car lovers test their need for speed in BMW Mission 3

- China stocks close mixed Monday