Revisiting Magritte

By Holland Cotter ( The New York Times ) Updated: 2013-11-10 07:58:33

|

|

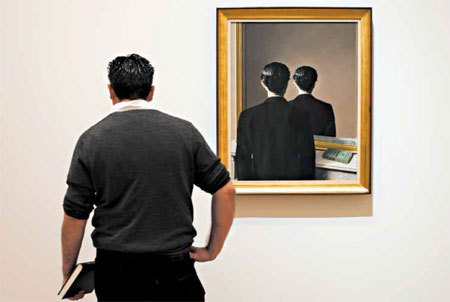

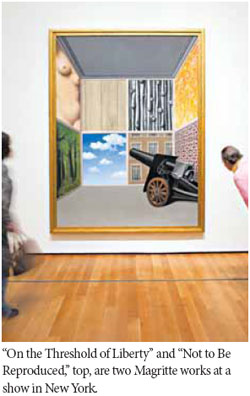

Photographs by Karsten Moran for The New York Times |

Oh, no, I thought when I heard that the Museum of Modern Art's big fall show was a Rene Magritte survey. Dozens of undersung modernist painters, many of them women, on at least five continents, have never had a New York moment, and here we're getting an artist we practically can't avoid. The pipe; the giant eye; the choo-choo in the fireplace.

As it turns out, "Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938," is good solid fun, because Magritte is solid and fun.

He was a sophisticated trickster, a bourgeois gentilhomme with a geek inside, hacking into everyday life and planting little weirdness bugs: legs sprouting from shirt collars, rain falling upward, words having lives of their own.

He was an attention-grabber with one gift, but a crucial one: for puzzle-making. You may not get, at first glance, what's going on in his paintings, but you get that there's something to get. So you look again. And again. Which is a marketer's dream.

One thing's for sure: We're unlikely ever to see Magritte look better than he does in the MoMA show, which runs through January 12. Its organizers have zeroed in on a consistently fresh and interesting decade in his long career, when he was inventing the artist he wanted to be and when his art was witty, nasty, brilliant and bad at the same time.

Born in the Belgian provinces in 1898, Magritte was tight-lipped about his early years. We know that his father was a tailor and cloth merchant, and that his mother committed suicide when he was 13. He trained as a painter at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. In his early 20s he married Georgette Berger, who would be his lifetime partner and model. He supported himself as a commercial illustrator and graphic designer.

But behind this staid lifestyle facade, vanguard

ambitions sizzled. By 1926, Magritte was moving in Surrealist circles in Brussels and making logic-defying collages and paintings that brought together landscape elements, domestic items and figures - female nudes, men in bowler hats - in stagelike settings. Daily life got a hallucinatory lift.

Ostensibly, Magritte's art, like most early modernism, had utopian dimensions: the shattering of social norms and perceptual givens in the interest of changing the world. Yet a world that might correspond to the one in "The Menaced Assassin" presents a dubious prospect. Its images of a decapitated woman and cudgel-wielding accountant, set in a spotless room with alpine view, is a kind of vaudeville of violence.

This picture, the first one you see at MoMA, was featured in Magritte's debut solo exhibition, in Brussels, in 1927.

The show was a critical flop but generated sufficient attention to encourage Magritte to move to Paris, the Vatican of Surrealism.

Once there, he lived in relative isolation outside the city and focused on his work. As a technician he was no great talent, which may contribute to his popularity. You never have to feel in awe of Magritte's painterly skill as you do those of a slick virtuoso like Salvador Dali. With a little practice - who knows - you might be able to paint like Magritte yourself. He wouldn't care. His real concerns lay in the what, not the how, of his art: in ideas embodied in images. To make those images legible and concise, and uncrackable, was the goal.

At least some of the paintings from the Paris years, which include several of his most famous, filled the bill. "The Lovers," with its cloth-shrouded kissing heads, was certainly one. "The False Mirror," with its single great sky-filled eye, was another. "Treachery of Images" was a third. Its shop-sign-style picture of a pipe labeled "This is not a pipe" is a crystal-clear advertisement for creative illogic.

Together, these paintings convey what was innovative about Magritte's bizarre art: its insistence, far in advance of Conceptualism, that art was a world of its own, a world of ideas.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face