|

|

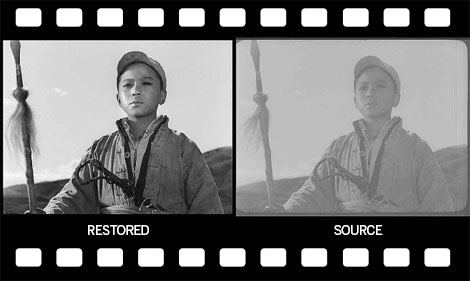

Top and above: Chinese feature films produced before 1958 are restored by the China Film Archive. Photos provided to China Daily |

|

|

A team from the China Film Archive restores old Chinese films. |

The restoration of old films in China largely depends on government assistance, but it is not a straightforward process. Liu Wei reports.

Vintage is the new sexy - and not only in the fashion industry. On Feb 24, a restored version of Hong Kong director Tsui Hark's 1992 film Dragon Inn hit theaters. In 2009, another Hong Kong filmmaker, Wong Kar-wai, had his 1994 film Ashes of Time restored and screened.

But other old films are not so lucky, as restoration is sometimes more difficult than making a new one.

Several years ago, China Film Archive wanted to restore Bridge, the first feature film after the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949.

Zuo Ying, vice-director of the archive's technical department, found almost all the flick's scenes shook. He and his colleagues could not tell whether the original release was like that or if the film was damaged later.

They could not start the restoration until they found the film's cinematographer, who was more than 80 years old, in a Beijing Film Studio dormitory. He told them the original images were stable and suggested the problem could be that the film stock had not been preserved properly.

To restore an old film does not mean it must become a brand new one. The restored version should be as faithful to the original release as possible.

Therefore, the restoration of old films is never just technical. It requires a team that knows about films.

Most of the archive restoration team members studied either computer technology or arts, but few excel in both.

"That's why I strongly recommended film experts and the original cast and crew members join the restoration," says Wu Jueren, a film restoration researcher.

The problem is, many of the original cast and crew members are too old or have passed away, which makes the repair of classic films more urgent.

The China Film Archive keeps about 27,000 films, one-third of which were made before 1949. The oldest is 1922's Laborers' Love by Zhang Shichuan.

Films made after 1958 are in better condition, because the archive's two climate-controlled vaults were built that year. Film stock from before 1958 is in urgent need of restoration, as the film shrinks, scratches and tears.

China started to restore old films in the 1970s. Since the 1990s, the film archive has been working mainly on digital restoration.

According to Sun Xianghui, vice-president of the archive, the institution has completely restored 106 films over the past five years.

On average, the archive spends 300,000 yuan ($46,000) to repair a film. This is a low figure compared to the restoration of classics in Europe and the United States. For example, the 1937 US film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs cost about $3 million to restore.

In China, the money for reviving old films comes mainly from the government, while in Western countries, various nongovernmental sources help. For example, Martin Scorsese's The Film Foundation is supported by fashion and wine enterprises, which love connecting their brands to the concept of preserving the classics.

Sun has been working to find more funding. In 2011, the archive and Swiss watchmaker Jaeger LeCoultre decided to repair 10 Chinese films over three years.

Wu, the researcher, believes classic films deserve the effort. "Just like Shakespeare's works and Mozart's music, classic films are the fruits of human creativity and civilization," he says. "They kind of change people's way of looking at the world."

Film restoration is a continuous process. A film may have different versions, due to censorship and the director's changing opinion, among other factors.

It takes great pains to find as much information about a film, such as the original script, stills, posters and old reviews, to really restore a film.

A famous example is the restoration of German director Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis, which took decades.

After its German premiere, much footage from the flick was lost. Discoveries of lost footage and efforts to restore the film continued over decades. A 2001 reconstruction of the film was shown at the Berlin Film Festival and considered a refined version, but seven years later, a copy of the film 30 minutes longer than any other known surviving version was found in Argentina.

New material was reinserted into the movie by restoration experts who compared every frame to adjacent frames, according to their understanding of the film.

"You can never say you have finished the restoration of a film. It is always being restored for a better version," Wu says.

There has been controversy about which way is better to preserve the classic films - to physically repair the film stock or to turn it into digital format.

Zuo, of the China Film Archive, believes it is not time yet to give up on traditional film stock.

"We have seen film stock made more than 100 years ago, but we have never seen computers made 100 years ago," he says. "We still need time to prove digital media is truly archival."

Preserving a film in the digital format makes it easier to copy and transport - and delete and tamper with - Wu Jueren says.

"At present, the most proven way to preserve a film, if it was shot with film stock, is to keep the original negative properly," he says.

All three experts agree that a film lives on when people see it on the big screen.

The China Film Archive showed some of the restored flicks at its theater in 2011, and Sun, the vice-president, says screening will continue in 2012.

The Shanghai Film Festival showed some old films last year, too. In 2014, 10 restored Chinese classics will be screened during the festival.

"Classics are not restored to be locked in vaults," Wu says. "They deserve the appreciation of future generations."