|

|

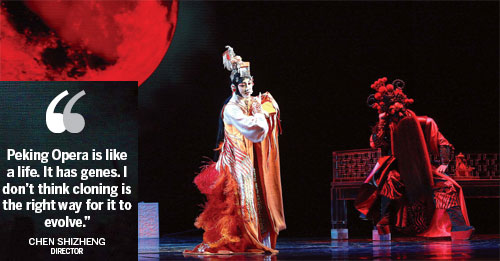

Farewell My Concubine is Chen Shizheng's first production in China. Photos by Zou Hong / China Daily |

|

|

Related: Mixing it up to add pizzazz |

A version of Farewell My Concubine challenges Peking Opera's pieties. But does it bend or break the rules, and for better or for worse? Chen Jie reports in Beijing.

When Peking Opera was inscribed on UNESCO's Intangible Culture Heritage list in December 2010, Chinese - be they performers or virtual strangers to the genre - celebrated with pride. But PoloArts Entertainment Co CEO Wang Xiang says it's a tragedy because "it means Peking Opera is dying and badly needs to be saved. But how can we save it? Is it impossible to revive it?" He wants to do something. When he met director Chen Shizheng in Beijing, in autumn, he found they shared many ideas about Peking Opera's destiny. These agreements evolved into the 50-minute Peking Opera Farewell My Concubine.

It opened at Reignwood Theatre on Feb 28 and has created a stir for its new adaptation of this old play.

Xiang Yu and Liu Bang were two rebel leaders fighting against the evil emperor at the end of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC).

But the final battle was Xiang Yu's waterloo. He drank with his beloved concubine Yu Ji for the last time. She performed a sword dance for him.

Then, she cut her throat with his sword.

Grief-stricken, Xiang Yu fought his way to Wujiang River and, when all his men had fallen, took his own life.

Peking Opera master Mei Lanfang (1894-1961) adapted the heart-wrenching story in 1922. It has ranked among the most famous Peking Opera plays since.

But Chen's version is very different from Mei's, which has become a model for generations of Peking Opera actors.

There is no traditional Peking Opera band onstage.

Only one jinghu, the two-stringed fiddle played in Peking Opera, accompanies Xiang Yu's and Yu Ji's arias in some scenes.

Two women drummers standing offstage hit big drums to kick off the show.

Dressed in a gorgeous qipao, eight women sit around the 138-seat auditorium, playing the pipa piece Ambush from Ten Sides, which depicts the same historical story but is never used in Peking Opera.

The show also features multimedia effects and seven white-faced dancers - Yu Ji's maids - performing modern choreography.

The martial artists perform fantastical kung fu as if they were in an action movie rather than in a Peking Opera performance, in which fighting is traditionally simple and routine.

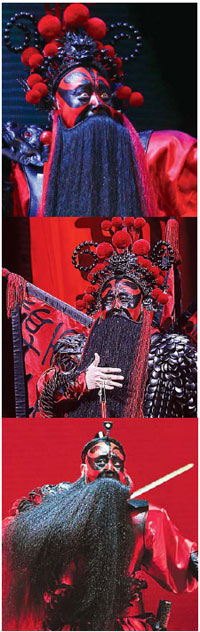

While these innovations might perturb purists, they would be infuriated to see Xiang Yu's face is painted red, rather than white, in the new show.

Different colors of face paint indicate different characteristics in Peking Opera - and always have.

But creating a "new" Farewell My Concubine that "breaks something old" is exactly what Wang and Chen set out to do.

Wang points out that Mei was famous for innovation in his time.

Farewell My Concubine is an old play, but Mei created new movements and used fashionable lighting and costumes in the 1920s.

However, for generation after generation throughout the last century, all the actors studying the Mei school of Peking Opera have merely imitated his every tiny gesture and never dared to "break" anything - especially convention.

Wang says there are two ways to preserve something.

"One is to keep it exactly as it is and not touch it, which is more like keeping it in a museum," he says.

"But Peking Opera is a live performance. It is a living entity that needs fresh air."

The director agrees with the producer.

"If you want to make an omelet, you have to break a few eggs," Chen says. "People always say we must inherit tradition. But what is real tradition? Is it superficial forms or some symbols?"

Chen believes it's a lack of confidence that keeps Chinese from changing old art.

"Peking Opera is like a life," he says. "It has genes. I don't think cloning is the right way for it to evolve."

The director is fascinated by the function of theater in contemporary life.

"Why do people go to theater?" he says.

"And, in this case, why do people in the 21st century go to see Peking Opera?"

Chen believes the core of the answer is the allure of drama and the ability - or lack thereof - to move audiences.

But in Peking Opera, storylines and characters have retreated to second place.

The old Peking Opera fans only care about the melodies, the singing or whether the performer is a "jue" (an established and popular actor).

New audiences, who aren't familiar with the arias or the actors, won't go to a show that has nothing to do with their lives.

"Though Master Mei made a graceful gesture to portray Yu Ji when she takes Xiang Yu's sword to cut her throat, audiences didn't cry over the tragedy because they just appreciated Mei's singing," Chen says.

Chen wants audiences to see a tragic love story: The couple is together for 10 happy years. But now she sees his power in decline. And he himself is clearly aware he has nowhere to go.

But neither say it.

When he returns after a defeat, she does not cry, complain or speak like a backseat driver. Instead, she tries to smile, serves him wine and says: "Shall I dance to make you happy and relaxed?"

In the final fight, she commits suicide to avoid distracting him from battle. Upon seeing the woman he loves die and watching his men fall, he kills himself in a heroic way.

"It's a double suicide," Chen says. "It's a relationship that's familiar to today's audiences."

Besides retaining the famous arias of Xiang Yu and Yu Ji, Chen tries to tell a touching story and portray real characters to let the show penetrate the audience's inner heart.

The pipa music in The Ambush from Ten Sides and the background video designed by Flora &Faunavisions from Germany highlight the intense and tragic atmosphere.

Many say the dancers' makeup and hairstyles resemble Japanese geishas'. But Chen says some old local operas featured white-faced women.

Chen studied Huaguxi, a local opera in his hometown Changsha, capital of Hunan province.

He adds that the dancers' hairstyles and choreography are derived from ancient Chinese pottery figurines and paintings.

"After all, they are not just dancing as Yu Ji's maid," he says. "The white-faced dancers in white dresses are another metaphor for ill omens. They give you a feeling that something bad is going to happen."

Chen's answer to questions about why Xiang Yu's face is red, is: "Why not?"

As he puts it: "Xiang Yu's white face in classical Peking Opera looks very sad. I consider Xiang Yu a hero. He's brave, tough and hot-tempered. Red fits the character and is the theme color of the whole show."

Changing makeup or adding video is relatively easy.

The challenge is changing the mindsets of the actors, who have received 12 or more years of Peking Opera training.

In Mei's time, Peking Opera had no directors - only jue.

The performers said "no" to the director at the first few rehearsals. They would often say such things as, "The steps are wrong", and, "My teacher didn't teach me in this way".

Peking Opera actors are accustomed to very strict form.

"They don't portray a character," Chen says.

"Instead, they simply perform or imitate their teachers' every moment."

The question of whether or not this is the right way to develop Peking Opera deserves discussion.

Wang and Chen hope people come with an open mind. "Western theater has thousands of interpretations of Hamlet," Wang says. "So, why must we accept just one Yu Ji?"