|

|

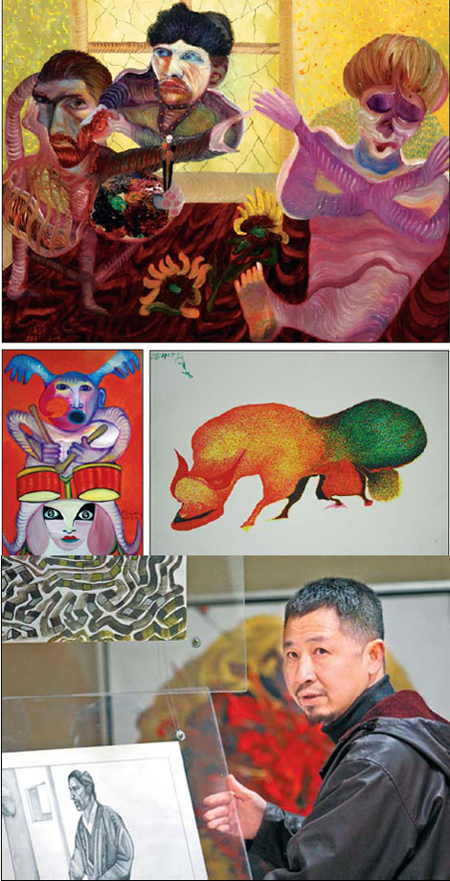

Clockwise from top: A work by Zhou Huiming, from Shanghai, on display at Nanjing Center for Natural Art; A work by Wu Meifei; Artist Guo Haiping sets up an exhibition at the center; A work by Zhou Huiming. Photos by Zhang Wei / China Daily |

Related: A creative approach to mental illness

An NGO helps patients with mental illnesses recover through engaging their creative talents. Zhu Linyong reports.

The first thing artist Guo Haiping does after he wakes up every morning is gaze into the distance through his bedroom window.

He's looking at Jiangxinzhou, a misty isle in the Yangtze River in southern Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu province.

"My secret garden is right there," says the 50-year-old, who founded the Nanjing Center for Natural Art, the country's first NGO dedicated to the collection, research and promotion of artistic creations by people with mental illnesses.

The center occupies less than 400 square meters and exhibits more than 300 works by artists with mental illnesses. It also has an art studio for visiting artists with mental illnesses.

"We receive telephone calls almost every day but get few visitors," Guo says.

Nanjing native Li Ben is a regular, who visits every two or three months.

"I paint whatever springs into my mind with free materials the art center provides," he says.

Not all people with mental illnesses have artistic talent, says Guo, who believes Li is a rare example.

Li has lived with schizophrenia for years. His last job was as a clerk for a savings bank in Nanjing's Jianye district.

"When the mental hospital puts the label on you, you become dangerous and useless in the public's eyes and can hardly find a job," Li says.

Li lives with his wife Qiu Fuxiu, a grocery store clerk, in a 6-square-meter garage they rent.

"Painting gives new meaning to my life," Li says.

He has been able to reduce the dosage of his medicine while remaining emotionally stable for 11 months since he began painting under Guo's guidance. His wife occasionally joins the creative process, giving him "more inner peace and satisfaction".

The art center has received fewer than 30 mentally ill people with artistic talent. Most are from Jiangsu and neighboring provinces, Guo says.

The center receives an annual sum of 300,000 yuan ($47,482), donated by entrepreneurs - just enough to keep the center open, says Guo, who works there as a volunteer.

The center can only offer month-long creative sessions for visitors from afar.

Wu Meifei, a 38-year-old manic depressive mental patient from Fujian province, spent three weeks at Guo's art center, where he tried to use different colors to draw animals, insects and vegetables last March.

"Wu's creations are equal to those of any other artist in China in technical merit, visual quality and aesthetic value," says Guo, who has been a professional artist for decades.

Meifei's elder sister, Wu Meihui, tells China Daily by phone: "The days at the art center were the happiest for my brother. When Meifei draws, he is focused, quiet and relaxed. The completion of a colored drawing makes him happy for days."

The sister hopes to maintain a long-term relationship with Guo's art center to help her brother live a better life.

However, Wu Meihui has become anxious after learning Guo's center is struggling for survival and may close down if he fails to garner enough support.

"It's my life mission to promote the art of the mentally ill," Guo says.

His first encounters with people with mental illness were his elder brother and his ex-girlfriend, who are both in a psychiatric hospital in Nanjing.

Guo began painting at 20 and reading books about psychology and psychiatry in the 1980s.

He opened the country's first hotline for people with psychological problems in 1989 in Nanjing, as a service branch of the China Youth League of Nanjing.

"From then on, I have set out to explore the intricate mechanisms of mental illness," he says.

He spent three months in Zutangshan Mental Hospital, starting from Oct 10, engaging in dialogues with mental patients, their families, psychiatrists and nurses, and guiding patients to paint or draw with pastels.

"The experience was enlightening," Guo recalls.

"It far went beyond the desired goal of performance art in which a professional artist interacts with mental patients, doctors and the public through media exposure. It changed my view about psychiatric patients forever."

It was then that Guo made a great discovery.

"All patients actually have rich and complex inner worlds, although they often disguise themselves in a veil of dullness, lethargy and submission, possibly created by medicines," he says.

And these disadvantaged individuals aren't always "disruptive and violent" as some believe.

Some patients told Guo they feel extreme fear and resentment about their life-long seclusion and isolation in the hospital.

Guo included these stories in the 2007 book Demented Art that he wrote with Zutangshan Mental Hospital psychiatrist Wang Yu.

Guo has delivered numerous lectures in universities and communities, held exhibitions of art created by the mentally ill and attended international forums on art by mentally ill people.

"We need to change the general public's prejudices toward, and misperceptions of, people with mental illness," Guo says.

He believes prejudice toward the mentally ill comes from a variety of sources. These include ignorance, a lack of communication between patients and the public, and misinterpretations in literary works, movies, TV dramas and media reports.

Art, Guo believes, is one of the best bridges to span the gap between the public and the patients.

"I hope to identify more talented painters among China's mentally ill and assist them to rebuild their lives, reclaim their dignity and eventually re-integrate into social life," he says.

But he has so far found himself on a bumpy road full of turns.

The absence of a mental health law has prevented him from approaching patients in hospitals and representing their artistic rights at art markets in and outside of China.

A lack of funding has prevented him from building a larger, permanent museum of art by the mentally ill and realizing his dream of organizing an international expo of their works.

"Guo's approach is inspiring to me," psychiatrist Wang Yu says.

"Art therapy should be a necessary component of mental hospitals' daily operations. That will surely have positive effects on patients in the course of their recoveries."

But Shanghai Mental Health Center head Wang Zucheng emphasizes artists and art therapists must work closely with psychiatric professionals. "Psychiatric patients need comprehensive care," Wang says.