|

|

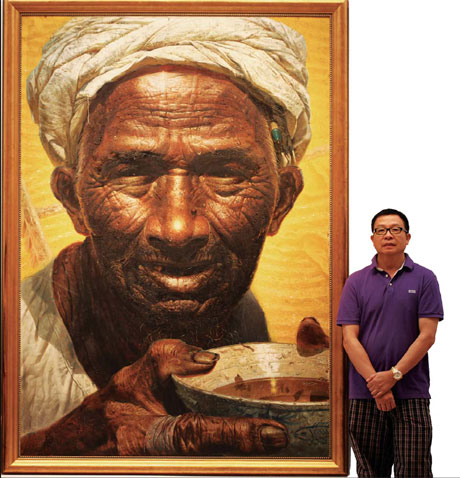

Luo Zhongli poses with his representative work, Father. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Luo Zhongli became one of the country's most celebrated artists for his depictions of farmers, but his ongoing retrospective reveals stylistic changes that divide critics. Zhang Zixuan reports in Beijing.

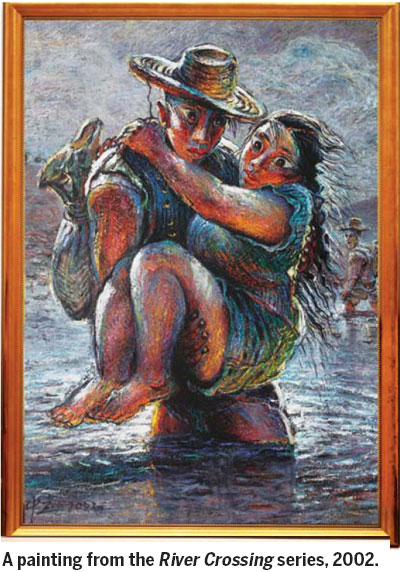

His mouth opens with chapped lips. His eyes exude worry and exhaustion. Gullied wrinkles carve his swarthy face, carrying sweat beads that are about to fall. The tea in the bowl his rough hands hold has become turbid. The Super Realistic image of a traditional Chinese farmer was painted in a Sichuan Fine Arts Institute dorm during the summer vacation of 1980. Junior student Luo Zhongli didn't expect his painting - named Father - would win gold at the coming Second National Youth Art Exhibition, and eventually become a milestone in Chinese modern art history. Nor did he anticipate the controversy that would swirl around the work after its debut.

The residue of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) still remained in the early 1980s.

One accusation said Luo's painting "smeared the image of laborers". More vitally, this old farmer's face was rendered as large as the portraits of Chairman Mao Zedong from that time.

"My core was the concept shift - the time of God has passed, and here comes the time of man, upon whom our livelihoods really depend," Luo explains.

More than 800 people voted for Father - 700 votes more than the second place winner received.

"For the first time, a painting featured the true color of laboring people, who used to be only painted in a bright way," critic Shao Dazhen says.

"It was a breakthrough in social ideology."

But that was more than three decades ago.

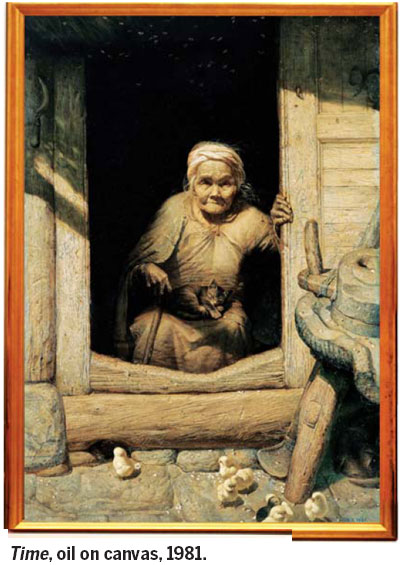

Modern life has made Father's time unimaginable. But Luo still portrays farmers.

More than 60 of his works are on show at the 20 Years of Glory - Mountain Art Foundation Collection of Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, nearly occupying the entire Hall No 1 of National Art Museum of China.

These works include his representative pieces, such as Sky and Spring Silkworms, which are contemporaneous with Father. There are also 40 pieces from the Hometown Series created from the 1980s until the early 1990s.

A larger retrospective solo exhibition of Luo's work will run at Taipei's National Museum of History from April 19 to June 3. It will show more than 100 artworks collected by Taiwan's Mountain Art Foundation since 1978 and several recent oil paintings and sculptures Luo personally provided.

"This will be Luo's most comprehensive retrospective," Mountain Art Foundation's president Lin Ming-che says.

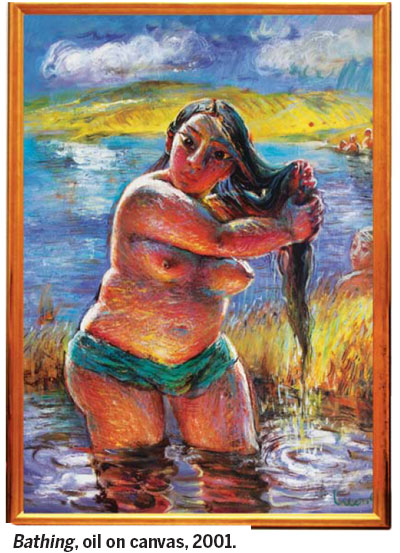

Farmers are the subject matter of all the works.

"The subject is infused in my blood," Luo says.

The 64-year-old lived in rural Chongqing's Daba Mountains for 10 years before getting into the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in 1977, when universities reopened after the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

The urban native still recalls what he saw when he arrived in the rural areas for "re-education".

He recalls the farming households took in the arrivals from the urban areas one-by-one.

"The torches and oil lamps they were holding looked like sparks scattered across the Daba Mountains' terraced fields," Luo recalls.

"It was a silent, slow-motion fairy tale."

Oil lamps and torches often appear in his works and have become something akin to his signature.

Luo also remembers the mountain farmers' pureness and diligence. The patriarch of the family that lodged him served as the inspiration for Father.

The work's composition was inspired by the spontaneous underground exhibition Weed in 1980, which set a precedent for the Scar Art School.

"We were excited yet blind and full of doubt about China's future development," Luo recalls.

At Weed, Luo and his schoolmates first expressed introspections about the "cultural revolution", by using vanguard subjects and strokes that orthodox institutes would not then recognize.

In one work, Luo portrays a man painting nude in a room with sealed doors and windows. Another shows an ambulance running into a bloodied pedestrian.

Luo's former roommate Zhang Xiaogang, now a leading Chinese contemporary artist, describes Luo as "the earliest avant-garde in our class".

"We were in a period of social transformation," Luo says.

"The old ideology had been proven wrong. But a new one hadn't yet formed."

Father's rendering is Super Realistic, but Luo calls it an "exception".

"My passion was Chinese ink painting," Luo says. "Although I majored in oil painting, I was never the best at it."

He says Father was meant to be his last stand for oil painting to prove to his classmates he could paint as Realistically as they did.

"The technique of Father can be accomplished by many well-trained painters today," he says.

"But what can't be reproduced is the specific time background. I got lucky."

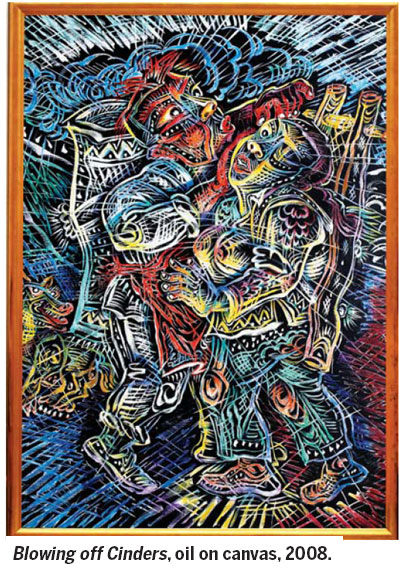

He abandoned Realistic paintings with political messages in the 1980s.

"They were not the real Luo Zhongli," Luo says.

"But they were real parts of Luo Zhongli. I have achieved success and no longer bear the financial burdens I used to. What matters is to return to the original passion of painting."

He kept farmers as his subject matter but switched to more Figurative and Expressionist styles. His interest in calligraphy and line drawing also led to new ways of using lines in his works.

But many fans who adored Luo's Realistic works were disappointed.

However, Luo says his style has become more sophisticated.

"The changes in my painting style adheres to a continuous arc that can be understood by professionals," Luo says.

"But the country's incomplete art education unfortunately interrupts ordinary viewers' appreciation and goes beyond the ability to judge whether something is like or unlike something."

Luo has been his alma mater's president for 14 years and believes this role has taken too much time away from painting. But it provides a higher-level understanding of art education.

Luo values students' independent creativities as much as their mastery of basic techniques. This has remained the school's tradition since he was student here, he says.

He also strives to provide better creation environments, so works like Father will not again have to be produced in crowded and messy dorms.

In 2000, he bought a 6,000-sq-m former military tank warehouse and renovated it into art studios.

A 54,000-sq-m art zone opened on the school's new campus. Any artist who has dreams can apply for an independent studio.

As the dean of Chinese Academy of Contemporary Art, Luo plans to publish a thorough documentation of contemporary Chinese art in three or four years.

He hopes the country will have its own National Contemporary Art Museum by then.

Luo still carries pens and paper wherever he goes and constantly sketches. His studio's light is the last to go off at night. "Just like someone who is addicted to smoking or drinking, I am addicted to painting without purpose or pressure," he says.

The artist visits the Daba Mountain area every year to seek inspiration.

His namesake art museum is under construction at the Chongqing government's order. When it's done, Luo hopes to provide a comprehensive demonstration of his creations.

"Good or bad," he says, "this is Luo Zhongli."

Contact the writer at zhangzixuan@chinadaily.com.cn.