|

|

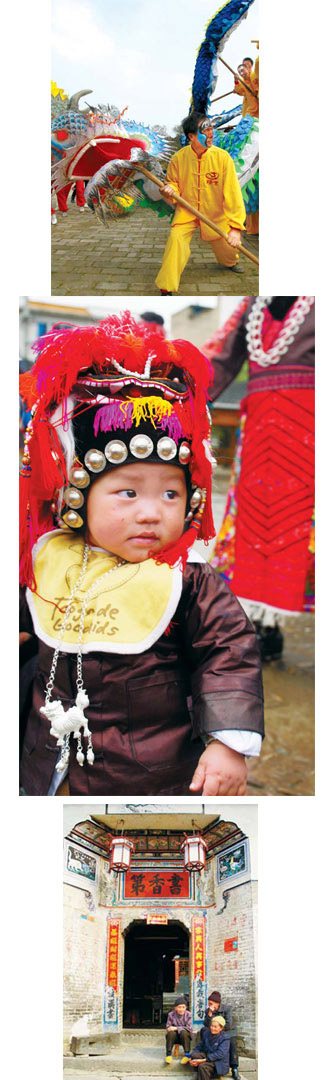

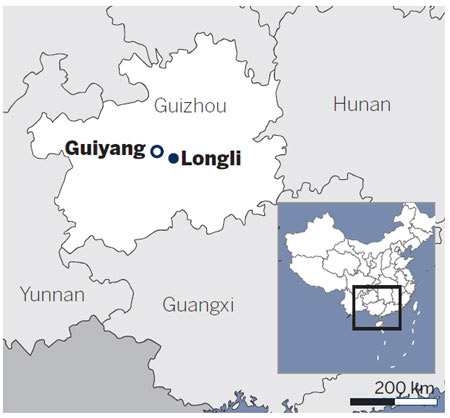

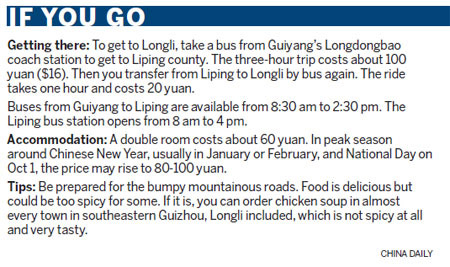

From Top Tongli residents rehearse the dragon dance, an entertaining ritual for every Lantern Festival. A Miao child in traditional costume in Taijiang, Guizhou province, known for its silver products. Characters on a house gate in Tongli read "shuxiang di", which suggests a scholar's family. Photos by Sun Licheng / for China Daily Liu Wei / China Daily |

The Guizhou province town was formerly a garrison populated by migrant Han people sent there by Ming Dynasty emperors, but is now concentrating on becoming an eco-museum. Liu Wei reports.

Longli, a small town in Guizhou province, has a fate that echoes its English name, which sounds a bit like "lonely".

The southeastern Guizhou town sets itself apart from the surrounding minority ethnic communities by its Han culture.

The first thing you will probably notice about the town is its architecture: white walls and dark blue tiled roofs with turned-up eaves and ridges, suggesting their origin in East China's Anhui and Jiangxi provinces.

The buildings are quite different from those found in Miao and Dong villages, two major ethnic groups among about 17 in southeastern Guizhou.

While the Han is the largest of the 56 ethnic groups in China, in southeastern Guizhou, Han people are a minority.

The first residents of the town, about 450 km from Guizhou's provincial capital Guiyang, arrived in the early Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

The then emperor sent officers and soldiers, mostly from South China, to build a garrison town. They brought not only their families, but also their culture, all evident in the city's layout, architecture, dress, language and rituals, such as the dragon dance every Lantern Festival.

I was lucky to see a rehearsal when I was there recently. Every dancer had his or her face painted with simple but colorful strokes, while the most eye-catching performer played the part of the dragon's tail.

Dressed in ragged clothes, he moved his body crazily and made funny faces to entertain the audience. He would run toward them suddenly, share food from a small bag he carried, or throw water from a wet broom at them. Those who received his food or water are supposed to be blessed.

Accompanied by fast and loud drumming, the ritual was lively and entertaining, but behind the thick makeup and vigorous movement is the sorrow and nostalgia of Longli's residents.

My local friend Yang Xiuting has been researching the town's history for years. He told me that about seven wars between the Han and other ethnic groups have been fought over the centuries.

Life became tough when the Ming Dynasty ended, as Longli residents used to get salaries from their emperors because they were sent here as an army. But they were no longer government employees when the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) started.

"The town was forgotten by the Qing rulers," Yang says.

In a brutal war in the mid19th century, many residents fled to the nearby mountains and stayed there.

The nostalgic local residents who stayed like to decorate their houses' gates with refined murals and big written characters, such as "shuxiang di" ("scent of books"), which suggests a scholar's family, or "guanxi di" (referring to a region) indicating from where the family emigrated.

Here, scholarship is highly valued, as when the town lost its value as a military fortress, more attention was paid to getting a good education.

The town has few inns and restaurants and life goes on, largely as it did for hundreds of years.

Vendors do not stop visitors as they rely more on local residents for trade. Old people play mahjong in the sunshine, while carefree kids run across the cobblestone roads.

I talked to an old lady basking outside her house near the town's entrance and on the main street. The location would be perfect for a tourist shop, but she said she had never considered opening up for business.

Beside her house a middle-aged woman was selling oranges. The scales showed the bag contained between 1 and 1.5 kg of oranges, but unlike big city vendors, instead of adding more oranges to make it 1.5 kg she took some out to make it 1 kg and then went back to her TV program.

The former garrison town is searching for a new role. Tourism obviously isn't flourishing yet, which means the town has an unspoiled flavor.

The local government seems to have realized the damage that over-commercialization can cause and has worked with Norwegian organizations to develop the town as an eco-museum.

The eco-museum concept sees the community itself as something to preserve.

Residents can choose to stay in town or move to a "new city" several kilometers away. If they want to refurbish their old houses or buy new ones in the new city, the government and a loan project by the World Bank offer financial aid.

Walking around I saw a notice posted by the local government about protecting the old town: "Any house renovations should maintain the original look."

The little town and its painful past deserve sensitive and careful development.