|

|

Beijing-based writer Sheng Keyi is attracting attention for her novels that focus on underprivileged women in Chinese cities. Feng Tang / For China Daily |

Related: Sheng's works

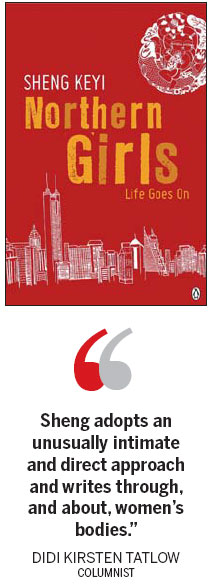

Sheng Keyi's novel Northern Girls: Life Goes On, tells of a migrant woman worker who has to deal with men's perception of her sexuality and the struggle for survival. Mei Jia reports in Beijing.

The struggles of a woman who migrates to the city in search of work is the focus of Sheng Keyi in her novel Northern Girls: Life Goes On. Shelly Bryant has translated the work, the first of Sheng's six novels, into English. "My focus in the novel is to examine how women from the lowest rungs of the social ladder make their way to the city and fight for their dignity," says Sheng, known for her realistic approach to writing.

Qian Xiaohong, the novel's protagonist, is a 16-year-old girl who appears to be a model citizen, but experiences unwarranted gossip and suspicion on account of her well-endowed body.

Qian is from a village in Hunan province and it is rumored that she was forced to leave because she had an affair with her brother-in-law. She joins other migrant workers who flocked to the country's south in the 1990s to seek a better life.

Qian works hard at a factory, salon, hotel and hospital.

In Shenzhen, locals often referred to migrant women workers as "Northern Girls" because they came from provinces north of Guangdong, with nothing but their bodies and their labor.

"What Qian experiences was shared by 70 to 80 percent of Shenzhen's migrant girls in real life," the author says.

Sheng, also born in Hunan in 1973, says Qian's character came to her when she was thinking about starting on her first novel.

"Qian has a strong character. She's frank, bold and has her principles."

Sheng uses Qian's ample bosom as a metaphor. In one scene in the book an official offers her 50 yuan ($8) for sex - a not insubstantial sum for the young woman who earns just 250 yuan a month.

Qian appears to accept the offer and begins to undress the man, but then escapes the room tossing the money at the official and saying: "I'm a virgin, uncle. I was just curious about your body. I'm giving you 50 yuan to put your clothes back on."

Jo Lusby of Penguin China, the book's publisher, says Sheng "presents a very different, inside view" that attracts an international audience.

Unlike other works on the subject of migrant workers, notably Leslie T. Chang's non-fictional Factory Girls, "Sheng adopts an unusually intimate and direct approach and writes through, and about, women's bodies", columnist and writer Didi Kirsten Tatlow says.

Tatlow says Sheng has addressed a key topic, namely "how a poor woman who attracts considerable male attention holds on to her morals in a highly amoral society".

The language of the novel is forceful and concise, mixing Hunan and Cantonese dialects; while the action is original and lively.

"Once I've set the tone, the narration and language style, the writing becomes smooth," Sheng says of her writing.

Writer and publisher Shen Haobo considers Sheng's style to be unique.

Shen says both Qian Xiaohong and Sheng have an attitude similar to that of Jack Kerouac in On the Road - strong spirited.

Unlike an intellectual's approach of pitifully looking down from above, "Sheng doesn't judge", Shen says. "She talks about Qian's survival in a straightforward manner."

Now based in Beijing, like Qian, Sheng originally moved from Hunan to Guangdong.

But unlike Qian, she started writing essays and short stories at junior high school.

She arrived in Shenzhen in 1994. After working at a security company, a hospital and as an editor on a student magazine, she left for Shenyang, Liaoning province, in 2001.

In Shenyang, she wrote Northern Girls, and her second novel, Water and Milk, also centering on young people, love and marriage, in Shenzhen.

Sheng says her main focus is on women in the countryside and the challenges of urban life.

Some say Sheng's colorful life experiences have brought profundity to her works.

Critic Meng Fanhua says Sheng is different from other post-1970 writers because she is not a showy writer.

"Her concerns about the situation facing people on the lowest rungs of society are a bridge connecting the country's valued literary traditions and their future," Meng says.

At the end of Northern Girls, Qian seems overwhelmed by her breasts, so much so that she feels clumsy. She lingers on a bridge near the train station, with no money, no job, no love - just like when she first arrived in Shenzhen.

"I want to stress that there are gender limitations that a girl can't totally step away from," Sheng explains.

Though some critics say the breast metaphor signals Qian's move toward feminism, publisher Shen believes otherwise.

"The seemingly surreal ending of a realist story shows that no miracle will happen to girls like Qian, and she has to keep moving on."

Contact the writer at meijia@chinadaily.com.cn.