However, after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Yu never saw Liddell again.

The school was occupied by Japanese troops and Liddell was detained in Weihsien (old spelling of Weixian, today's Weifang, Shandong province) Internment Camp, which imprisoned more than 2,000 Westerners living in China, including 300 children.

"He had the chance to leave for Canada with his pregnant wife and two children, but he refused to leave his brothers in church behind. I guess that must have been a tough decision for him," Yu says.

Liddell continued teaching class and organizing games in the camp. Norman Cliff, a British Christian at the camp, later wrote a memoir declaring: "(Liddell is) the finest Christian gentleman it has been my pleasure to meet. In all the time in the camp, I never heard him say a bad word about anybody."

Although Japan offered a prisoner-of-war exchange plan after early 1944, three times, allowing about 200 internees to be released, Liddell would not leave. Though on the British government list he gave up his place to children. He died of a brain tumor six months before Japan surrendered.

"His loyalty greatly inspired me," Yu says.

Yu joined the United States Marine Corps, stationed in Tianjin in 1946, as a part-time bar tender at the military club to cover his living expenses at college, as his family's business failed. When US troops left China, his commanders were satisfied with his job and wanted him to go to the US.

"They even promised US citizenship, but I refused. I told them, `I am Chinese'," Yu says.

However, this experience and his family background caused Yu a lot of trouble during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). He was an ordinary worker at a post office for decades, even though he speaks excellent English and has finance and engineering degrees.

Yu did not speak about TACC or Liddell for years, until Aug 29, 1993.

On that day, he accidentally met David Mitchell, an Australia-born Canadian from a Hong Kong-based foundation in memory of Eric Liddell. Mitchell was 9 when he was imprisoned at Weihsien Internment Camp.

"He offered me a photocopy of Liddell's death certificate at the camp," Yu says. "It was supposed to have been destroyed by the Japanese when they retreated."

Mitchell told him a Christian Japanese soldier secretly preserved the certificate when he was supposed to destroy it.

The nostalgic Yu was excited to collect more relevant material and completed the book, Li Airui's Brief Biography, in 2008.

Yu has now completed a revised version of the book and expects to get it published by the end of 2012. He also plans an English version of the book.

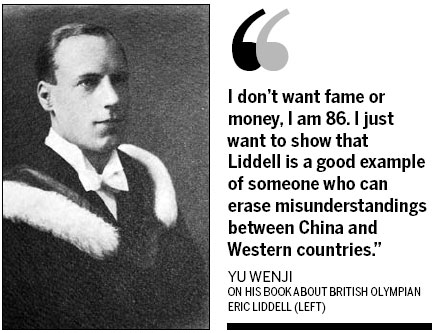

"I don't want fame or money," he says. "I am 86. I just want to show that Liddell is a good example of someone who can erase misunderstandings between China and Western countries."

He is delighted to see people paying more attention to Liddell during the current Olympic Games, but he also hopes it is not a fad.

TACC buildings were destroyed in the devastating Tangshan earthquake of 1976. After several renovations, Minyuan Stadium is also being demolished. The only other building related to Liddell that is still standing is the hospital where he was born.

Jin Pengyu, a cityscape and architecture expert in Tianjin, who is helping promote Yu's book, says the municipal government plans to build a sports museum in 2013, which will introduce Liddell's story. Yu says he is happy to provide materials.

Yu also formerly had a brain tumor like Liddell. His life was saved after an operation in 1999. He later got baptized, decades after attending missionary school, to mark his rebirth.

"Maybe my eyesight and brain are not that keen after the operation, but my memory of Liddell is always fresh."