|

|

Japanese columnist Kato Yoshikazu regards China as his second home. Jiang Dong / China Daily |

|

|

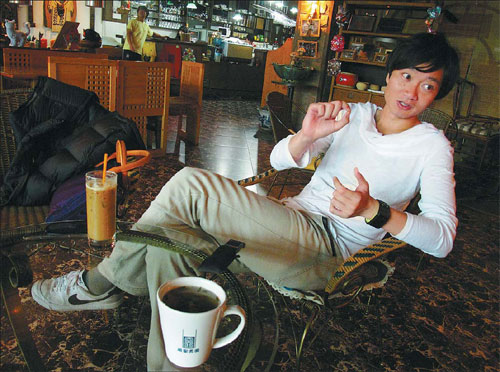

Kato arrived in Beijing in 2003, when he was 19. Provided to China Daily |

My China Dream | Kato Yoshikazu

He has spent the better part of his 20s in China, studying, observing and writing about what he sees. Now, Kato Yoshikazu is leaving and he shares his thoughts with Mei Jia in Beijing.

Twenty-eight-year-old Kato Yoshikazu is probably the best-known Japanese columnist in China, on China. But soon, he will be going to the United States, leaving behind all the fame and blame he has accrued over the years. In the last few years, Kato has published more than 1,000 articles and some 20 books in three languages on China. They cover multiple aspects of Chinese society and offer a unique perspective for both Chinese and foreigners.

He also appeared frequently in the media, sharing his views, or coordinating forums and seminars.

Most of his works and speeches are in Chinese, for he's a fluent Mandarin speaker and writer, who gives no hint that he's a foreigner when you speak to him on the phone.

But he believes that leaving may let him understand, observe and interpret China even better, from a distance. He says his fate is already bound with China, and he regards China as his second home.

"I was there when China was being watched intensively and when the world was curious to know more about it," he says. "I was there sending my voice out in Chinese and now, I will try my best to establish myself as a world-level expert on China.

"As a China watcher, I know I will rise if the future of China rises, and I will slide if the country is to slide down."

Kato says his American plans were forged three years ago, and denies it was in response to the recent furor he raised when he made remarks about the Nanjing Massacre during a public speech in May. After he showed ambiguity on the historical facts of the tragedy, Kato was swarmed by angry Chinese netizens. A scheduled speech at a university was cancelled.

"I take that event as a lesson," he says thoughtfully at a cafe near his alma mater, Peking University, earlier this month, on the eve of his departure.

"I learned not to be too self-assured, and not to touch the bottom line," he says. He says he still thinks he emerged the winner, because the experience of being chastised has added to his work and made him both subject and object of his research on how the Chinese think and react.

"I was misunderstood, for I never denied the fact of the massacre," he says.