A modern literary classic gets a stage makeover, touching the heartstrings of a new generation and cementing Huang Bo's status as one of China's most solid thespians, writes Raymond Zhou in Beijing.

Q & A with Huang Bo: A stage play enriches again and again

It is a bit early to proclaim the most powerful stage performance of the year, but Huang Bo in To Live is certainly a strong contender. During the first run of the play, from Sept 4 to 9 at the National Center of the Performing Arts, the comedian put himself squarely among the best of the country's dramatic actors, evident from the tears and cheers of the audience who greeted him. Yu Hua, whose novel of the same name served as the basis for the stage adaptation, was amazed at Huang's feat. Memorizing the enormous amount of lines alone must have been an arduous endeavor, he said. The three-hour play follows the original story very closely, another point for endorsement by the author. To Live chronicles the life of an ordinary farmer, Fugui, played by Huang Bo, who started as a good-for-nothing and ended up a symbol for the helplessness and suffering of a nation.

The protagonist epitomizes the resilience of the Chinese people and the survival instinct he displays in his tumultuous life. It is a testament to the national character we often take for granted.

The acclaimed novel was made into an equally acclaimed film in 1994 by China's top filmmaker Zhang Yimou. Though never formally released, it has been available through discs and online downloading.

To put it briefly, the play stands solidly on its own, without a whiff of fear of being overshadowed by its big-screen predecessor, and Huang Bo brings out the black humor and the human dignity in his own way.

Meng Jinghui's stark and avant-garde directorial style fits the subject matter, stripping the tale of superfluous details. The rows of furrows where actors pop up and vanish are ingenious as stage design, and lighting enhances the innate drama.

But, there is an inconsistency in the treatment, with the modern dance music and French song somewhat incongruous with either a realistic or an abstract approach.

Huang's slapstick background served him very well in bringing out the light touch of the play. His slightly roguish method of tricking a fellow villager out of his pancakes, more than once, illustrates the famine, a most heartbreaking episode of history, with a poignancy that elicits both tears and laughter.

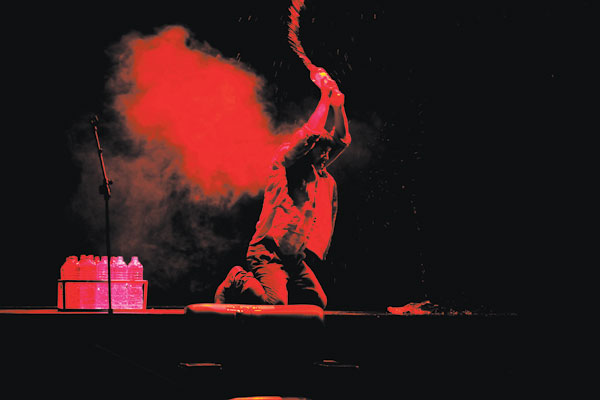

His smashing of a string of water bottles upon hearing of his son's death is no doubt one of the most indelible images on the Chinese stage. Like the water that is splashed all over, the pain the character endures oozes from the stage and permeates every corner of the hall.

It is an image that will stay with you for a long, long time.

Huang Bo is the furthest thing from a matinee idol.

Related: A love letter to Shanghai

His breakout in the 2006 sleeper hit Crazy Stone puts him in the category of the buffoonish Everyman.

His success is the antithesis of the nationwide pursuit of movie-star charisma. He may not always get the girl, but he has a firm lock on the type of roles that people can identify with.

As if that is not enough for a busy career, Huang has segued from urban comedies to heavier and more dramatic roles that take on allegorical overtones.

Cow in 2009 and Design of Death in 2012 plumb the depths of not only the simpleton who stumbles into historical chapters, but a sort of prototype that cuts to the bone of the national psyche. The former won him the coveted Golden Horse for best actor.

With To Live on stage, he shows that his screen tour de force is by no means the product of editing. He has the acting chops to tackle the most demanding of dramatic roles.

Fugui may have barely survived, but Huang Bo has triumphed - against all odds.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.