Love and loathing from the footnotes of history

By Zhao Xu( China Daily )

Updated: 2018-11-26

|

|

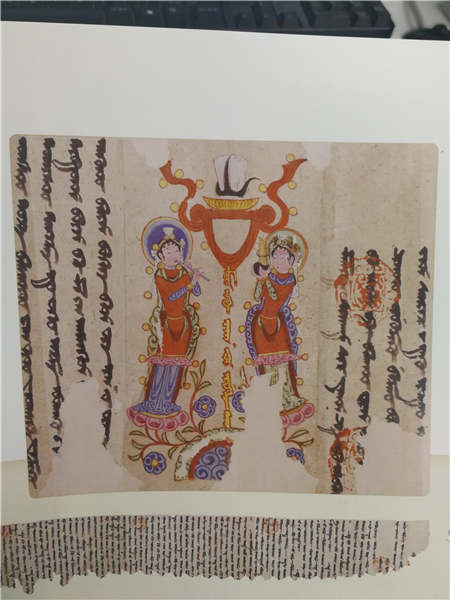

A 10th-12th century letter in Sogdian script, unearthed in Xinjiang [Photo provided to China Daily] |

The rebellions - another erupted soon after - were not completely put down until 763. Part of the blame was placed on the Sogdians, whose signature leaps and twirls, once part of Tang's dance routines, were now viewed as a deluding force.

This was not totally unjustified. An Lushan, a good dancer despite his plumpness, was believed to have first swirled himself into the favor of Yang Yuhuan, herself well-versed in dance and music. Meanwhile, Emperor Xuanzong, the self-proclaimed king of music, had taken under his personal tutelage more than a few Sogdian artists.

Forever gone was all the confidence and optimism associated with a golden era in Chinese history, and an openness that was a byproduct of that confidence.

At one time the Sogdians, after staying in China for more than three years, could officially register as Tang citizens. Some became court officials, their elevated status mirrored by the resplendent funerary objects filling their tombs.

However, not everyone was affected, Mao says.

"By the time people changed their attitude, many Sogdians had been living in China for so long - some were second - or even third-generation immigrants - that they had long stopped feeling like foreigners. The backlash sent little ripples across the local Sogdian community, although trade along the Silk Road did wane."

An Pu and his son An Jinzang were lucky enough not having to live through all this. The son, a court musician who served the crown prince during the reign of Empress Wu Zetian (624-705), the only female monarch in Chinese history, earned himself a page in the annals of Tang, through a rare act of loyalty.

According to historical record, the empress, after receiving secret report that her son, the crown prince, was plotting against her, ordered an investigation. All who were close to the prince were thrown into torture chambers where confessions were extracted

An Jinzang was not immune. But he did not flinch. Instead, he cut his own abdomen with a knife, shouting to his investigator: "Let my heart prove what my words cannot."

However, he did not die. The empress, deeply shocked, ordered prompt treatment for him and the immediate closure of the case.

The crown prince later became emperor and was succeeded by his son, Emperor Xuanzong, during whose reign the rebellions took place. An Jinzang, for his part, lived a long life and died in 731, having made a nobleman by the grateful father and son.

"His story reads more like a martyr than a merchant or mercenary," Mao says.