Beaten, but not broken

By Rena Li (China Daily) Updated: 2015-08-11 07:57

|

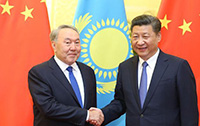

A photo taken on liberation day, when George S. MacDonell (back row, fourth from left) and other prisoners of war were released from the Ohasi camp on Sept 15, 1945. Provided to China Daily |

George S. MacDonell is one of a small number of Canadian survivors of the Battle of Hong Kong in 1941. Now 93, the veteran recalls the battle, Japanese prisoner of war camps and the courage of his Canadian comrades. Rena Li reports from Toronto.

In November 1941, 2,000 young Canadian soldiers crossed the Pacific Ocean and landed in Hong Kong to fight the Japanese army, which was occupying the then-British Crown Colony. More than 500 of them never returned home.

George S. MacDonell had just turned 18 when he quit high school and answered the call from the Canadian government for volunteers to fight in World War II. "We suddenly found ourselves in a culture which had been writing sophisticated poetry before Canada was discovered," the 93-year-old veteran recalled in an interview at his home in Toronto. "Our time on the island was a wonderful experience at one of the crossroads of the world."

That "wonderful experience" would end the next month. On Dec 8, the same morning the Japanese attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, 80,000 Japanese soldiers backed by airplanes and a naval force attacked Hong Kong.

"We didn't know that the Japanese were going to try invading the entire area of Asia. We didn't believe that the Japanese were so foolish as to take on China, Great Britain, the United States, Australia and Canada," said the veteran of the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment.

About a week into the battle, the Allied forces - volunteer Chinese troops, plus units from Canada, Britain and India - received a message from Britain's wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill, that read: "Do everything you can to buy time, but never surrender. Do not give up the island. Fight with the Chinese as long as you can, and harm the Japanese army as much as you can."

Surrender and captivityBut the Japanese military force was too great. On Christmas Day, after 17 days of fighting, the Canadians were defeated, and the British governor of Hong Kong ordered them to surrender.

"We never put our hands in the air to the Japanese, and never laid down arms until ordered to do so," MacDonell said. "The Royal Rifles never quit during the battle in Hong Kong or in those ghastly prison camps in the following years."

The fighting in Hong Kong ended with many casualties for the Canadians, with 290 men killed and 493 wounded. Following the battle, MacDonell and his compatriots would spend almost four years in Japanese prison camps in Hong Kong and Japan.

The POWs were sent to a camp in Hong Kong at Sham Shui Po, and the worse the prison conditions became, the more determined the men of the Royal Rifles were not to crack, according to MacDonell.

During the Canadians' time in the camp, members of a Chinese anti-Japanese guerrilla force planned to attack the occupiers, rescue all the prisoners and take them to China.

"But disaster struck. The Japanese discovered the plot and those young officers were tortured and executed," MacDonell said.

After about a year in captivity in Hong Kong, the Canadian prisoners were sent to a camp at Kawasaki, a suburb of Yokohama in Japan. They worked as slave labor in the Nippon Kokan shipyard, the largest in Japan, where freighters and naval vessels were built.