Beaten, but not broken

By Rena Li (China Daily) Updated: 2015-08-11 07:57

|

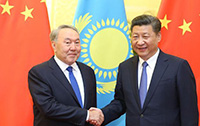

Veterans in Vancouver honor Chinese soldiers who died during World War II and the Japanese occupation. Liang Sen / Xinhua |

Shipyard sabotage

Despite having to endure terrible conditions, the prisoners found ways to sabotage the Japanese shipbuilding efforts. Two of the men, Staff Sergeant Charlie Clark and Private Stanley Cameron, both Torontonians, set a fire under the yard's blueprint factory, where wooden forms were patterned. The blaze was timed to occur at night when the prisoners were back at their camp, more than 3 kilometers away.

"Burning the blueprints and the patterns that came from them meant there was no way you could build a ship or do anything in that shipyard," MacDonell said. "They did it in utter secrecy; they told no one. But they pulled it off, and even saved their own lives by doing so undetected. This shows the spirit of the Canadians who, even after they were taken prisoner, decided to never give up, never accept the Japanese, and to keep fighting."

Long after, when MacDonell met Clark and congratulated him about the successful sabotage, Clark simply smiled and said, "It went rather well, didn't it?"

The Canadian POWS were moved to a camp in northern Japan until they were freed in 1945 after the Japanese surrender. It was a nerve-wracking time because the prisoners feared their captors would kill them rather than set them free, a perception underlined by a Japanese order of the time that read: "Do not allow the escape of a single one - annihilate them all and leave no trace."

On Sept 15, 1945, US forces picked up the Canadians at a nearby port.

Looking back on the Battle of Hong Kong, MacDonell said: "Too little has been said about the Chinese volunteers who fought with us, and who went to prison camps with us. They were extremely brave, and we were very proud that we were associated with them. And they suffered very heavy casualties too."

He said the history of the battle "is not about how the Canadians were defeated. It's about how they fought and how they behaved against impossible odds. And it's about the mettle they showed when it was apparent that there was no hope and there was no possibility of a successful outcome. They never surrendered and they fought like tigers."

After the war, MacDonell returned home and finished high school, then studied for a bachelor's degree at the University of Toronto. He married Margaret Telford, a young professor at the school, when he was studying for his MA, and they had a son and a daughter.

As part of his master's studies, MacDonell wrote a term paper about labor relations at Canadian General Electric Co. The paper caught the attention of H.M. Turner, then-president of the company, which led to MacDonell being hired in 1950 and spending 20 years in CGE's management ranks, eventually becoming vice-president.

He retired from the company in 1970, and then worked for other employers before being appointed as Ontario's deputy minister of industry, trade and technology in 1984.

In the early '80s, MacDonell believed that China would be a great export market for Ontario because of the country's enormous population and the growing demand for a more-modern lifestyle.